A sharp eye for design

- Share via

Saul BASS falls into that category of artists whose imagery has become far more recognizable than their names. You may not have heard of Bass, but his designs provided nothing less than a defining aesthetic for an era of American popular culture.

Chances are you’ve been seeing his work most of your life without realizing it, in darkened movie theaters, along the sides of jet planes, hidden in your spice cabinet and even emblazoned on your telephone bill. His visual aesthetic has become so omnipresent as to be almost invisible, integrating itself easily into the fabric of our everyday life.

For the record:

12:00 a.m. Feb. 21, 2003 For The Record

Los Angeles Times Friday February 21, 2003 Home Edition Main News Part A Page 2 National Desk 1 inches; 45 words Type of Material: Correction

Bass exhibit phone --The phone number for information regarding the “Saul Bass: Designer” exhibition at the Hollywood Entertainment Museum was listed incorrectly in an article in Thursday’s Calendar Weekend. The correct phone number is (323) 465-7900.

Throughout the 1960s and ‘70s, Bass was responsible for creating corporate logos for clients such as AT&T; and United Airlines, enduring imagery still used by each company today. But it’s his prolific film work that has most influenced contemporary graphic design. Hired by directors such as Otto Preminger, William Wyler and Alfred Hitchcock to create title sequences and promotional graphics, Bass produced a wonderfully distinct iconography built from basic block fonts and bold illustrations.

The Hollywood Entertainment Museum (which has a Bass-designed logo) is holding a retrospective of the artist’s work, a collection of vintage movie posters, lobby cards and intricately produced press kits that go a long way in illustrating Bass’ immense impact on the design world.

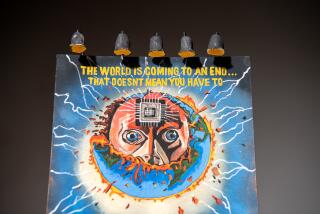

Reminiscent of Soviet poster art of the ‘20s, Bass’ style was unapologetically symbolic, powerful sloganeering conveying a film’s narrative premise in a one-page print ad or a three-minute opening sequence. He had a particular knack for distilling imagery to its essential elements, the resulting visuals left bare-boned and all the more powerful for their simplicity.

“It’s really incredible when you see all of his work together like this,” says Chris Horak, the museum’s curator. “In some cases, the imagery is more famous than the films.”

Bass’ work is as unforgettable as it is familiar. Attempting to both “symbolize and summarize” with his designs, Bass proved himself to be one of the most prolific and sought after graphic artists in the world, a creator who left his mark on everything from Academy Award posters to Girl Scout logos to the architectural design of a series of Japanese gas stations.

“He really did everything,” says Horak. “ He directed, he illustrated, he animated. He was continuously involved in several mediums.”

Born in New York City in 1920, Bass moved to Los Angeles at age 26 and opened Saul Bass & Associates, quickly making a name for himself with his striking publicity graphics for Hollywood movies.

In 1954, he shot his first title sequence, for Otto Preminger’s “Carmen Jones,” a year later creating the now renowned poster for Preminger’s “The Man With the Golden Arm.”

Instead of relying on celebrity photos and film stills, Bass opted for no-frills ink and paper and sleekly clean illustration to promote a movie’s main themes. His success was due in large part to the fact that he knew the power of paring down ideas to their absolute basics.

For “Man With the Golden Arm,” Bass chose as a symbol a disembodied arm, for “Anatomy of a Murder,” an illustration of a fragmented body. He provided edgy graphic accompaniment to Hitchcock’s “Vertigo” “North by Northwest” and “Psycho,” working closely with the director on the latter film’s shower scene. Eventually Bass would also direct, winning an Academy Award in 1968 for his documentary short “Why Man Creates.”

By the 1970s however, Bass had moved away from film and toward substantially more lucrative corporate design work. But his movie imagery would endure.

Later in his life, Bass would allow himself to be lured back to Hollywood once again, hired by directors who had come of age admiring his work. He created title sequences for films such as “Big” and “The War of the Roses,” and worked with Martin Scorsese on “GoodFellas,” “Casino,” “Cape Fear” and “The Age of Innocence,” a creative partnership that was ended by his death in 1996 of lymphoma.

Bass’ passion had been to create visuals that would convey complex ideas in the simplest of forms. In the process he managed to invent a style that would push graphic design into a new era. “Looking at his work you see how much of it was later copied and how much you directly relate his images to a certain time,” Horak says. “Bass was truly one of kind.”

*

‘Saul Bass: Designer’

Where: Hollywood Entertainment Museum, 7021 Hollywood Blvd., Hollywood.

Ends: April 13.

Info: (323) 464-7900 or www.hollywoodmuseum.com.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.