Secrecy Thieves Love Nice Guys

- Share via

Corporate security is an illusion. So is personal financial privacy. I should know; I spent five years of my life in federal prison for proving it.

A recent survey by the Computer Security Institute and the FBI found that 90% of U.S. firms responding had detected security breaches during the preceding year. Many companies believe that they can protect their information and networks from the bad guys by acquiring security technologies such as firewalls, anti-virus software and biometric authentication systems. But while it’s essential to use technology to prevent and detect hackers, it is naive to rely on technology alone.

I know because hacking was what I did before March 2000, when I pleaded guilty to breaking into a series of computer networks around the country.

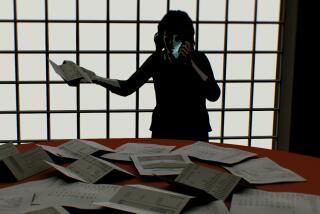

The greatest vulnerability for computer security doesn’t come from technological flaws in hardware and software but from the weakest link in the security chain: people. And not just dishonest employees. Trusted insiders can be duped or deceived into giving away the keys to the kingdom. The technique is called “social engineering,” and it’s a modern version of what I call the art of deception, which con men have been using for centuries.

An attacker, foreign or domestic, can easily take advantage of the trust we have in fellow employees and the respect we have for people in authority. For example: A caller tells you that there has been an ongoing problem with your server and you’re in danger of losing all your data. He needs to put you on another server; you’ll have to change your password and stick with it until the problem is resolved. He gives you a new password to use and waits while you make the change and verify that it works. You hang up, a little annoyed at the interruption but maybe feeling good that the people in information technology are taking such good care of you.

But was that really a man from IT, or a hacker who now has access to your computer system?

It’s not just business and government agencies that are the targets. One of today’s fastest-growing crimes, identity theft, often uses the very same techniques against individuals.

What’s more, your personal information is not private at all. Anyone with Internet access and an anonymous prepaid phone card can, in just a few minutes, obtain your driver’s license number, Social Security number and mother’s maiden name and the names of your spouse, children and pets. Much of this information is readily available on the Internet or through one or two social engineering telephone calls.

In the movie “Catch Me If You Can,” protagonist Frank Abagnale Jr. illustrates the art of deception behind social engineering attacks. By impersonating authority figures -- a pilot, a doctor, a lawyer -- he influences his victims’ attitudes and gains their trust, enabling him to pass bad checks all over the world.

The hacker who uses social engineer tactics steals your trust in much the same way. Consider: Your phone rings and on the other end of the line is a man from the phone company. He says you have an overdue balance of $63.14, and if it isn’t paid by 5 p.m., your phone will be disconnected and you’ll be required to make a $300 deposit before service is restored.

You insist that you paid on time. The caller says no payment was received and that a disconnect notice was mailed to you. In the spirit of good service, the man offers to search the records to see if he can locate the payment. This drags on for some minutes while you hear him clicking keys and making occasional comments. He still can’t find anything, so he asks you to get out your checkbook and give him the details of your bank, check number and amount of payment. Still nothing. He asks you to read off the numbers printed at the bottom of your checks.

You have just given him your checking account number. Before long, unfamiliar checks begin being cashed from your account or the hacker obtains access to your charge accounts by going through information gathered from the checking account. One key to preventing this from happening to you, at home or at work, is to be vigilant about verifying the identity of anyone requesting sensitive information.

“Loose lips sink ships” was a slogan meant, during World War II, to educate military personnel and civilians on the importance of maintaining secrecy of troop movements. Now is a good time to update it to promote awareness of tricksters who may want your company’s secrets or to hijack your personal credit history: “Be alert or you’ll lose your shirt.”