Experts: Smart Case Tough to Solve

- Share via

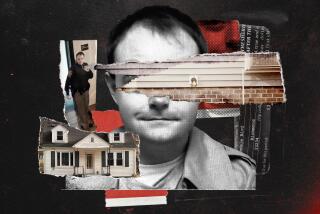

SALT LAKE CITY — Police here have admitted mistakes in their handling of the Elizabeth Smart kidnapping, but some crime and child-abduction experts are not so fast to blame investigators. They say that abductions by strangers are among the most difficult to solve and that, in light of the bizarre circumstances of the case, local officers appear to have put out a solid -- if flawed -- effort.

The Smart family was among those who accused the department of being overly aggressive in its investigation of suspect Richard Ricci and too passive in its pursuit of the man found Wednesday with Elizabeth, Brian David Mitchell -- a panhandler and self-professed prophet.

Mitchell and his wife, Wanda Barzee, are being held in the Salt Lake County jail on charges of aggravated kidnapping. Police suspect Elizabeth’s abduction may have been a plan to collect multiple wives for Mitchell.

But as late as December, even Elizabeth’s father had advised caution in placing too much stock in the only eyewitness to the crime: the teen’s younger sister, Mary Katherine.

“That room was very dark at night,” Ed Smart told Associated Press. “What Mary Katherine saw or didn’t see is really hard to know.”

Authorities faced “a terribly hard job” in the days and weeks following Elizabeth’s June 5 abduction from her bedroom, said Bob Smither, founder of the Laura Recovery Center Foundation, a Texas-based group that helped organize the first searches in the hills above the Smart family home.

Because of the “phenomenal” community support -- more than 8,000 volunteers scoured the region’s rugged terrain -- police were bombarded with an equally phenomenal number of leads, Smither said. It may sound counterintuitive, but sometimes too many leads can bog down an investigation.

In the first month after the kidnapping, more than 10,000 tips came in. The task force eventually assigned to the Smart case consisted of 100 investigators, most of them Salt Lake City Police Department detectives, along with some FBI agents.

Compounding the number of leads was the number of transient laborers -- more than 50 -- who had worked in and around the Smarts’ million-dollar home, doing various jobs such as yardwork and construction in the previous year.

Most of the “persons of interest” police questioned were transients or laborers who had prior contact with or lived near the Smarts.

The first of the high-profile suspects was 26-year-old Bret Michael Edmunds, a small-time crook who was known to sleep in his car near the Smart home. A milkman said he may have spotted someone who looked like Edmunds lingering around the house. The drifter, found hospitalized in West Virginia, was cleared.

For a short time, investigators focused on an Orange County man, James Witbaard, a convicted sex offender who had connections to the Provo, Utah, area about an hour’s drive from here; but he too was cleared.

The man police spent the most time building a case against was the 48-year-old Ricci, a criminal and drifter who had worked for and stolen from the Smarts. Ricci was jailed for parole violations nine days after Elizabeth’s disappearance and was in custody when he became the primary person of interest.

Ricci died of a brain hemorrhage in August, proclaiming his innocence to the end. Some Salt Lake City officers firmly believed Ricci was the man they were looking for and that the secret of Elizabeth’s fate had died with him. After that, the case seemed to deflate and, by December, the number of investigators on the task force shrank to six.

October proved a pivotal month in several ways. That was when 9-year-old Mary Katherine gave her parents a description of the man she believed was the kidnapper -- a clean-cut, soft-spoken transient who called himself Emmanuel and had done roofing and yardwork for the family almost a year earlier. Mary Katherine shared a room with Elizabeth and was present, feigning sleep, when Elizabeth was taken away.

The Smarts told police about Mary Katherine’s description and even had a sketch made. But the man who headed the investigation, Capt. Cory Lyman, decided not to make it public. Lyman now says he did not take it seriously enough, and was afraid of wasting time on false leads.

“Obviously it was the wrong choice,” Lyman said in an interview. He has since left the department to become police chief in Ketchum, Idaho. “We didn’t do anything wrong per se, but we didn’t do the right thing, and I wish I could have it back.”

It was a judgment call, he said.

Frustrated by the lack of developments and seeking help from all avenues, Elizabeth’s family in December turned to John Walsh and his television show, “America’s Most Wanted.” After the show aired in February, the Smarts held a news conference and released the sketch.

Within days, the suspect’s sister gave authorities his real name.

It’s now known that Mitchell, Barzee and Elizabeth were in the San Diego area from October through February. They had returned to the Salt Lake area, and on Wednesday, passersby recognized Mitchell’s face from the sketch and called police. The three were in custody within minutes.

“I believe our family did our own investigation and I believe it brought Elizabeth back,” said the teen’s uncle, Dave Smart.

Kidnappings of children by strangers make for one of “the most difficult crimes” to solve, said Michael Gibson, president of a group called Operation Lookout -- the National Center for Missing Youth, which is based in Everett, Wash.

Gibson said up to 80% of abductions are committed by family members or friends. Often these suspects leave a paper trail: credit card purchases, gas stops, bank withdrawals. But when the kidnapper is a stranger, especially a transient who is not likely to leave a recognizable trail, it’s hard to know where to start the investigation.

“People think solving crimes is a science,” Gibson said, but in reality “it’s serendipity, dumb luck and skill. It’s more an art than a science.”

Bill Gaut, a retired police officer, crime consultant and lecturer, said there are risks involved in releasing a kidnapper’s identity too soon. Gaut said the main risk is that the kidnapper might panic and kill his victim, and that’s one of a multitude of factors police must consider.

Since the arrests Wednesday, the Smart family has refrained from criticizing police, saying publicly that everybody makes mistakes.

Salt Lake City Mayor Rocky Anderson said Thursday he would consider assigning a citizen panel to investigate police handling of the case. On Friday, the mayor said he would postpone the investigation until after Mitchell and Barzee have been tried.

Lyman said that through all the talk of mistakes and flaws in the system, it’s important to remember the outcome: Elizabeth is back home with her family, and the two suspects are in jail awaiting charges.

Said Lyman: “The end result is the ultimate judge.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.