Experimental Treatment May Be Used to Fight SARS

- Share via

After years of disappointment, an elegantly simple medical technique that targets bad cells while leaving healthy ones alone could be making a comeback in the high-profile fight against cancer and the SARS virus.

The technique, known as “antisense,” aims to kill the genetic messenger carrying disease. Despite all its promise over the last two decades, the field has brought just one obscure drug to market -- treating an eye ailment in AIDS patients -- and has left numerous failures and jaded researchers in its wake.

Now comes antisense’s first legitimate shot at success. Cancer patients are taking an experimental drug based on the method, Genasense, in three pivotal trials.

The results are expected in the next few months. Scientists, analysts and Genta Inc., the Berkeley Heights, N.J., company that makes the drug, are optimistic that at least one trial will lead to Food and Drug Administration approval of Genasense.

“The one thing this field has needed is one gigantic drug out the door,” said Genta’s chief executive, Raymond Warrell. “What the field desperately needs is economic success.”

Genta has spent 15 years and $350 million developing Genasense, which targets several types of cancer, including adult leukemia, and has been tested on 900 patients.

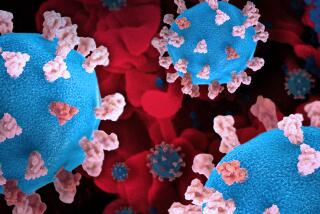

Hope for the technique is also rising in Portland, Ore., where AVI BioPharma Inc. is promoting its use in an experimental treatment for SARS, or severe acute respiratory syndrome. AVI says its drug Neugene, which targets West Nile virus, has been tweaked to take on SARS, which has infected thousands of people around the world.

AVI has struggled for 23 years to make even one approved drug. Few outside the field had heard of the company until the SARS outbreak prompted a global search for solutions.

AVI’s lagging stock price has doubled over the last two months and it recently got a $15-million cash infusion from bullish investors.

“Antisense is really beginning to reach its potential,” AVI CEO Denis Burger told a congressional subcommittee exploring ways to combat SARS.

Antisense drugs jam vital genetic signals by tackling targeted RNA, which carries DNA’s instructions to the body. Antisense scientists create mirror images of the RNA messenger that is spreading illness. When injected into the body, the mirror image bonds with the RNA and prevents it from delivering its message to protein-building machinery.

“It’s like cutting the wires from central command to the troops,” said Patrick Iversen, AVI’s top scientist. “All I need to know is what gene I have to screw up.”

In theory, the bull’s-eye technology is nimble and adaptable. It took AVI a matter of days to rejigger its antisense work on a coronavirus in mice and West Nile virus in penguins to attack SARS.

But some longtime experts are skeptical of AVI’s chances of success against SARS.

Dr. Cy Stein of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York, widely hailed as an antisense pioneer, said he needed to see much more data from AVI. Further, he points out that his field is littered with failures.

“We still don’t understand a lot,” Stein said. “It’s extraordinarily complex.”

The latest high-profile antisense drug flop occurred in March, when a large human experiment conducted by Isis Pharmaceuticals Inc., based in Carlsbad, Calif., and Indianapolis-based Eli Lilly & Co. failed to prolong the life of lung cancer patients.

It turns out the dummy genetic material often does more than just snip communication between bad genes and their deadly proteins. Many antisense drug candidates have been found to affect other genes and proteins not implicated in disease. Still others have proved ineffective in snipping the wires.

Nonetheless, Stein said he still was “chasing the dream” of antisense, especially as a cancer treatment. He said Genta’s antisense drug, Genasense, was the most advanced and promising candidate on the horizon.