‘Brinkley’s’ eye tends to the wry

- Share via

Brinkley’s Beat

People, Places and Events That Shaped My Time

David Brinkley

Alfred A. Knopf: 224 pp., $22.95

*

“In my view, television news tends more to reinforce the existing social and political values than to change them,” writes television anchorman and commentator David Brinkley in his posthumous memoir, “Brinkley’s Beat: People, Places and Events That Shaped My Time.”

“The recurring cry that it and other news media excessively influence public opinion in one political direction or another seems to me an empty claim,” he continues. “It must be if, after a half century of news reporting that has been regularly charged with being excessively liberal, we have recently elected some of our most conservative presidents.”

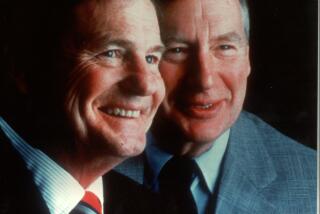

Brinkley died at 82 last June after 50 years of reporting, anchoring and commenting. He came to fame as the sardonic half of the NBC evening anchor team with Chet Huntley, and he later moved to ABC with the pioneering Sunday show “This Week With David Brinkley.”

“To survive, an anchor must convince some millions of people that he is at least modestly competent, that he has some idea of what he is talking about, and that he is playing straight with them, and that is about all,” Brinkley concludes. An anchor, he adds, “is famous only for being famous.”

He leaves out, though, the one element that perhaps counts the most in how anchors and commentators influence the way viewers perceive the news, and that is temperament. Walter Cronkite’s temperament, commonly called avuncular, was steady; Dan Rather’s is more aggressively combative. Brinkley’s was more than wry; it was in large part disdainful of many of the people, most of them politicians, he talked about.

“The American people,” Brinkley writes, “tend to believe little of what they hear from their government; they tend to assume that whatever they are told by political leaders is a pack of lies ... [and] remarkably often, they are right.” Another word for that attitude is “cynicism.” It can be argued that Brinkley in his long years in broadcast news made no little contribution to public cynicism toward politicians -- deserved or not.

Characteristically he writes that President Lyndon B. Johnson’s hopes for improving the conditions of Americans’ lives through government action “inspired dreams of something like utopia,” an obvious impossibility, he says, “because deep down inside most Americans is an admiration for those who have overcome difficulties and risen to achievement by their own efforts.”

Like nearly all TV personalities his age, Brinkley got his start as a newspaper reporter, and in his accounts of people he encountered, he displays a reporter’s eye for the telling detail. He recalls some people now nearly forgotten, like the odious and ignorant racist Sen. Theodore Bilbo, a Mississippi Democrat, and Rep. Martin Dies, the opportunistic Texas Democrat who served as the first chairman of the notorious House Un-American Activities Committee. He is a little gentler on FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover -- “the perfect bureaucrat” -- and even on Republican Sen. Joseph R. McCarthy of Wisconsin, emphasizing his personal kindness, charm and alcoholism in addition to the damage he did to so many lives in his publicity-inspired pursuit of Communists here, there and everywhere.

Brinkley’s generally neutral approach to his subjects darkens and tightens when he discusses Robert F. Kennedy. He writes that he did not share “in the love affair that so many Americans had with John F. Kennedy” -- he disliked their father, the use of family money to win elections, the family’s connections with McCarthy and John Kennedy’s seamy personal life.

But for Robert Kennedy, whom he considered a friend, Brinkley shows real feeling. “To me, Bobby’s death was the hardest of all to take [after the assassinations of the president and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.], partly because he was my friend,” Brinkley writes, “but also because I had never previously believed that the country was really in serious trouble.

“I had always thought that there were enough smart people with enough goodwill to pull us out of the mess we were in. And the shooting of Bobby Kennedy caused me for the first time to wonder if that was true. Sometimes I still do.”

Brinkley’s sad words about the death of his friend and the future of his country stand out in a memoir that mostly reflects his own aloofness in a lifetime of broadcasting to the nation about its hopes, disappointments, triumphs and defeats in the tumultuous last 50 years.

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.