Anton Burg, 99; Built USC Chemistry Dept. Reputation

- Share via

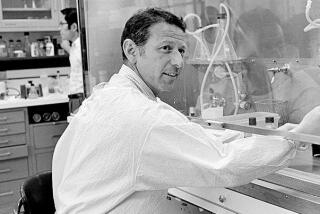

Anton Burg, 99, once the world’s leading expert on boron and the father of chemistry at USC, died Wednesday at his home near the USC campus in Los Angeles. No cause of death was given.

USC had a minuscule and undistinguished chemistry department when Burg joined the staff in 1939 -- “only one step ahead of alchemy,” in the words of one official. The emphasis was solely on teaching and no research had been performed there for years.

Within a year, the young assistant professor had become chairman of the department and embarked on a hiring program that, within a decade, made the department one of the nation’s best.

“By the early 1950s, we were third in the United States in funding per faculty member and fifth in publications,” said chemist Sidney Benson, one of Burg’s hires.

Chemist Arthur Adamson, another of Burg’s hires, recalled that the university’s president was surprised by the changes in the department.

“He was used to very subservient chairs. But Burg would not jump, and he wouldn’t hesitate to stand up for what he thought had to be done,” Adamson said.

But Burg’s passion was the study of boron. In 1927, Burg heard a lecture by chemist Gilbert Newton Lewis, who “said that nobody understood the chemistry of boron hydrides,” Burg recently recalled. He made it his business to do so.

First at the University of Chicago, and later at USC, Burg synthesized a host of boron compounds that subsequently came to have wide use in organic chemistry as tools for making more complex molecules. None of his creations became household names, but along the way he was one of the first people to see polyethylene and Teflon, both of which appeared as byproducts of his boron reactions. He recorded them in his notebooks as interesting molecules and went on with other things.

One of his practical products was a boron-based rubber that is now used in environments where it must resist high temperatures. The U.S. Army also approached him to make rocket fuels based on boron compounds -- which have very high energy densities -- but the work was aborted when it became clear that one of the reaction products was a glassy material that clogged the nozzle.

In 1934, Burg suggested that one of his young students, Herbert C. Brown, follow up on some reactions that he had discovered. The work eventually led to a Nobel Prize for Brown.

“Burg never published his initial results,” Benson said. “Brown always said that if he had published, they would have shared the Nobel.”

Anton Behme Burg was born Oct. 18, 1904, in Dallas City, Ill., the grandson of a German immigrant who made a fortune building carriages. He attended the University of Chicago, excelling as both a student and an athlete. His specialty was the high jump, and he was nationally ranked.

In 1926, the 5-feet-11 Burg cleared 6 feet 6 1/4 inches. The winning jump in the 1924 Olympics was 6 feet 6 inches. Burg barely missed qualifying for the 1928 team.

His athletic interests later turned to bicycling. Although he lived in Los Angeles for 64 years, he never owned an automobile, preferring to bicycle everywhere. His ability to get around startled others.

“After we moved to Palos Verdes in 1950,” Adamson said, “my wife and I would have annual Christmas parties for the faculty and other friends. Anton bicycled all 20 miles to get there.”

In 1994, Burg noted that he had gone through eight bicycles so far. “Of course, three of them were stolen,” he added.

Benson recalled how Burg prevented fire marshals from condemning an old Army barracks that USC was using as a chemistry lab in 1946. The marshals were concerned because there was only one exit from the second story.

Burg jumped out a second-story window, landing easily and yelling out, “See, that’s all there is to it,” Benson recalled. “The Fire Department approved the lab for use.... We ended up using it for another 20 years.”

Burg retired in 1974, but kept coming to his lab to continue his research. Following the 1994 Northridge earthquake, Benson recalled, his colleagues searched all over for Burg to inform him that his building had been condemned and he couldn’t enter. When they finally located him, he was in the lab making repairs.

Burg never married. A memorial service will be held Wednesday at 7 p.m. at the United University Church on the USC campus.