Rwanda’s Laity Isn’t Forgetting

- Share via

NYANGE, Rwanda — In the end, Charles Kagenza’s faith was stronger than the hallowed hall that once stood here. Even after all that has happened, Kagenza wanted to come to the Catholic church -- where he still prays every Sunday for God’s grace, the place where thousands were forsaken.

In fact, the proud brick temple that overlooked three valleys is gone. There’s just rubble, a couple of lonely pillars and a large mass grave.

Small and somber, Kagenza, 41, has a crease in his scalp and a blanched eye set in a broken socket, testament to the wounds he suffered here nine years ago. In this tiny mountain village, the half-blind stonemason is the only living witness to the final days of Nyange Catholic Church.

“When the killings began, many of the Tutsis in this village ran to the parish because we had the hope that none would have the courage to attack the church,” Kagenza said. “In 1973, there were also massacres and many fled to the churches and survived. So we had trust in the parishes and the priests.”

For about 100 days in 1994, Rwanda went absolutely mad. Militiamen, police officers, national troops and civilians led by the ethnic Hutu government engaged in a carefully organized government plan to kill people believed to be Tutsis, an ethnic minority in Rwanda, and Hutus sympathetic to them.

Not even churches were safe. Thousands of people ran to chapels for refuge, but most of the time church authorities were unable to stop the Hutu attackers. In a few cases, priests and nuns were unwilling to help, and some even turned against their flocks.

According to estimates by war crimes prosecutors, about 20 Catholic officials are awaiting trial in Rwanda’s genocide courts and a number of others are under investigation. Two-thirds of Rwandans are members of the Roman Catholic Church, the most influential institution in the country after the government.

Compared with the 120,000 Rwandans awaiting trial for involvement in the genocide, the number of suspected church employees is small. And priests were also victims of the slaughter, which left an estimated 800,000 Tutsis and moderate Hutus dead.

But much as molestation scandals have rocked the Catholic Church in the United States, genocide prosecutions of nuns and pastors have marred the Rwandan church’s reputation and plunged the country into a deep spiritual crisis, according to religious leaders and adherents.

The church’s image has been further damaged, many parishioners and critics say, by the Vatican’s refusal to accept any blame for the genocide on behalf of the Rwandan church. Two years after the slaughter, Pope John Paul II said individual church officials should be held accountable for any crimes, but he denied any institutional responsibility for the genocide, even though the church has had close links with every Rwandan government since the country gained independence in 1962, including the regime that planned the killings.

The church’s critics note that while the Vatican has deflected collective blame, it has paid legal fees for accused church officials, aided fugitives from the U.N. International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, denounced genocide prosecutions and occasionally tried to discourage war crimes witnesses from testifying against church employees.

“The Catholic Church has lobbied against the courts and against other reconciliation efforts as the government tries to rebuild the country,” said Privat Rutazibwa, a Rwandan journalist and former Catholic monk.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that the church’s actions have driven many Rwandans away from Catholicism. Pentecostal churches are on the rise as Catholics have switched to Protestant denominations. Other Catholics have turned to Islam, although that remains a small minority faith in Rwanda.

But the most pervasive sign of Rwanda’s spiritual struggle, according to many Rwandan Catholics, is a shift in the way many church members worship. Many Catholics say their disappointment in the church hasn’t broken their faith -- but it has been tempered.

Church members such as Dancila Nyirabazungu say they believe in God and even the sanctity of the church, but don’t trust their priests.

“The priests did nothing for us,” said Nyirabazungu, who lost 17 relatives at Ntarama Catholic Church, in southeastern Rwanda. “We used to think the priests were without sin. We used to think they had the role of God. But they’re like everyone else. And the church is just a house where you can pray without the sun shining on your head.”

Kagenza, who survived the Nyange church massacre here in western Rwanda, said, “I don’t put my faith in priests anymore, I just believe in God.”

On April 10, 1994, Kagenza and thousands of other Tutsis packed into the church to escape marauding militias. On April 15, Kagenza looked down from his hiding place in the bell tower and saw a Hutu horde massing around the parish.

Days of Horror

Hutus attacked the church over the next two days, firing automatic weapons and tossing grenades through windows.

“I could hear ladies screaming, I could hear children -- they were all dying,” he said. When the church was finally quiet, the Hutus poured gasoline over the bodies piled in the hall and set them alight. The brick bell tower survived the flames, and Kagenza and 50 others endured the smoke by breathing through their clothes.

Then two bulldozers rumbled up the hill. From his charred perch, Kagenza saw village officials ordering one of the bulldozer operators to raze the remnants of the church to finish off the survivors -- and the driver hesitating to commit the deed.

“The driver was afraid,” Kagenza recalled. “So he went to Father [Athanase] Serombe and asked him three times: ‘Do you agree that I should destroy this church?’ And the father said: ‘Destroy it. The most important thing is to survive the cockroaches [the Tutsis]. We will rebuild the church afterward.’ ”

Then Nyange’s pastor thrust the equivalent of $500 into the driver’s hand, according to later court testimony. With that, the bulldozer toppled the ruins.

Kagenza said he awoke as militiamen tried to pull him away from the rubble. They were not trying to save him -- they thought he was dead.

“I don’t know how I stood -- but I did, and I called to Father Serombe,” Kagenza said. “He asked me, ‘Who are you?’ I said, ‘It is Charles’ -- he knew me because I led Bible classes at the church. He asked me, ‘What can I do for you?’ I told him, ‘I need you to carry me away from this place,’ and he laughed at me.”

Serombe turned away as someone with a machete hacked into Kagenza’s head, he recalled. Another man swung a club into his face.

Kagenza later woke up again to find himself surrounded by the remains of about 2,500 Tutsis. Most of the Hutus had gone, so Kagenza crept down a mountainside and found refuge in a nearby convent.

After the genocide, Serombe fled to Italy. In 2001, international tribunal investigators discovered him working in a church near Florence. Serombe, who had been using the alias Father Anastasio Sumba Bura, had been conducting marriages and hearing confessions at the church. Before the investigators could arrange his arrest, the Vatican took him to another parish it refused to identify.

Delayed Justice

After intense international pressure on the Vatican and Italy, Serombe was extradited to Arusha, Tanzania, the headquarters of the international tribunal for Rwanda. Serombe, who has denied all charges against him, is awaiting trial and faces a life sentence. Kagenza said he would testify against him.

Other indicted priests have been arrested in Cameroon, the Netherlands and Switzerland.

A Belgian court handed down two of the first convictions against Catholic officials in 2001 when two Rwandan Benedictine nuns, Sisters Maria Kisito Mukabutera and Gertrude Mukangango, were sentenced to 12- and 15-year prison terms, respectively.

The court heard evidence that Mukabutera and Mukangango handed over thousands of Tutsis hiding in their abbey to government militias. Witnesses also testified that the nuns supplied the gasoline that Hutu attackers used to burn down a garage sheltering 500 Tutsi refugees.

According to witness statements and court documents, Catholic leaders in Belgium sent several emissaries to Rwanda to dissuade other nuns from testifying against the accused women.

After the nuns’ convictions, the Vatican issued a statement suggesting the church had been used as a scapegoat.

“The Holy See cannot but express a certain surprise at seeing the grave responsibility of so many people and groups involved in this tremendous genocide had been heaped on so few people,” according to the statement by a Vatican spokesman.

Accused church officials have been more successful at defending themselves in Rwanda’s national court. Two priests, who had received death sentences after being convicted of assisting the massacre at Nyange, were acquitted on appeal in 2000.

But such acquittals have not kept congregations from dwindling. Bishop Augustin Misago of the southern diocese of Gikongoro was the highest-ranking Catholic genocide suspect in Rwanda before his acquittal in 2000. He was accused of refusing shelter to 30 schoolgirls fleeing death squads and of betraying three Tutsi priests, who were executed by Hutu militiamen.

Misago testified that he turned away refugees because his church compound didn’t have room for them -- a contention disputed by several witnesses. Misago also testified that he attended genocide planning sessions with local government leaders only to encourage peace. And he testified that he tried to protect the three priests, even offering to pay off the militiamen with $1,600. But after government soldiers presented arrest warrants for the men, Misago said, he turned them over.

Misago spent a year in jail before his acquittal. Upon his release, he was immediately reinstalled at the Gikongoro diocese. Sitting in his parish offices after a Sunday Mass this month, Misago acknowledged that church attendance was down. The percentage of Gikongoro residents who attended Catholic churches fell from 46% before the genocide, he said, to 29% in 1996. The percentage has increased since then, Misago said, but not to pre-1994 levels.

Misago blamed the Rwandan government and Protestants for “trying to humiliate the church.”

“I don’t deny that one or two priests might not have done the right thing,” Misago said. “The pope himself called on every member of the church who had made mistakes during the genocide to confess their mistakes and ask for forgiveness. But the church will not ask for forgiveness, because we didn’t kill anyone and we did not ask [the militias] to come to the churches.”

Advent of the Church

Rwanda was among the last African realms to be proselytized by European powers. The Catholic Church arrived in Rwanda around the turn of the 20th century and expanded after 1916 when the kingdom became a Belgian protectorate.

The Belgians and the church favored the Tutsi ruling elite until the 1960s, when the monarch began pushing for independence. The colonial administration and church fathers then decided to back the nascent Hutu Power movement, which abolished Rwanda’s monarchy, established majority rule and led reprisals against the Tutsis.

From then on, the church became increasingly pro-Hutu. Catholic schools excluded Tutsis, and church documents show that priests routinely referred to them as the inyenzi, or cockroaches.

“The Catholic Church was as powerful as the state,” said Tom Ndahiro, Rwanda’s human rights commissioner. “They were twins. The state was a coercive machine. And the church lubricated that machinery.”

Recently, the relationship between the church and the new Tutsi-Hutu coalition government has taken a testy turn, with President Paul Kagame’s administration occasionally making derisive comments about Catholic suspects and the church taking tough stands on perceived human rights abuses by the ruling party. Religion and politics, however, are still tightly interwoven in Kigali, the capital, where the presidential palace sits next door to the archbishop’s.

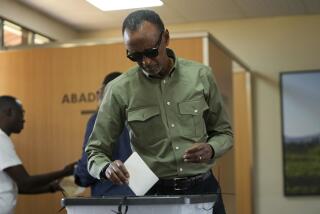

But with Kagame receiving 95% of the vote in elections last month, many ordinary Rwandans seem to have more faith in the government than in the church.

Louise Karwera, 42, lost all of her siblings, her mother and her father in the Nyamata massacre.

As in Nyange, thousands crammed into the church believing that priests would save them. Instead, the pastor drove away as Hutu militias advanced with blades, guns and explosives.

“Many of us in Nyamata hated the Catholic Church because they did not try to protect the people there,” she said. “They just left. Does a father leave his children? Is that what Jesus would do?”

Karwera has never been back to the Nyamata church -- or any Catholic church -- since the genocide.

Like many former Catholics, she attends Zion Temple Pentecostal Church in Kigali. Zion’s pastor, Richard Muya, is bullish on evangelism, having opened several churches in the region.

“This is where people can start again,” he said. “The Catholics come here with wounded hearts, and here they can heal. They know they are safe here.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.