Great Depths of Knowledge Await Below

- Share via

You can’t accuse the Bush White House of excessive imagination. The president’s latest “vision” is a replay of a 40-year-old idea stolen from JFK: men (and women) heading for the moon and beyond by 2030. Real creativity would set that crew down in another place altogether: the deep ocean floor.

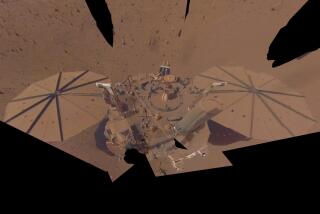

Although oceans cover more than 70% of the Earth, less than 5% of them have been mapped with the same degree of detail as Mars, and that was before the two most recent Mars rovers, Spirit and Opportunity, landed. We have rarely ventured below 6,500 meters in the oceans, although they reach more than 11,000 meters deep. We know much less about the ocean floor and the deepest layers of the oceans than we know about either side of the moon. And yet, the potential payoffs are huge.

Pundits gush over the fact that space exploration has led to its share of new technology -- for instance, NASA says the coatings that allow space capsules to withstand the heat of reentry have been used in building better pots and pans, and the miniaturization demanded by the small quarters on space vehicles has advanced such fields as laparoscopic surgery. But deep-sea expeditions could yield similar and perhaps even greater benefits. In order to freely explore the oceans’ deepest reaches, we must learn to construct submersibles that can handle extreme pressure, as much as 18,000 pounds per square inch. The resulting materials and techniques might help us design and construct homes that can withstand being buried in debris after an earthquake or a mudslide.

I hope you are not one of those Americans who hears NASA talking about life on Mars and imagines that we may find little green men who will ally themselves with us against the Chinese. The reference is merely to cells of organic material that may be present in the planet’s dust and rock. In contrast, the deep oceans are packed with complex, mysterious, intriguing creatures. In fact, it is estimated that there might be up to 2 million marine life forms that are yet to be discovered. Whenever we venture deeper, we find new species such as lithistids, a rare kind of sponge present only in deep waters. Such discoveries are likely to reveal secrets of life on Earth and even make up for other species that are being lost due to human expansion on the surface.

Mars’ organic limits mean that it is hardly a place to look for new medicines, unless one wishes to carry red mud millions of miles back to Beverly Hills so that we can all get Martian facials. But like jungles, deep-water habitats teem with life and contain the promise of new drugs and new cures for diseases. In what are still largely unexplored deep-water reef communities, the Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institution in Ft. Pierce, Fla., has already discovered what is believed to be an anti-tumor agent (discodermolide); its value for humans is being tested now in clinical trials.

And there may be other answers under the sea to Earth’s pressing problems. Scientists believe that organisms in the deep oceans can consume the methane that is seeping through the ocean floor and convert it into energy for themselves. Some theorize that we could learn to harvest such energy for our own use.

And how do Martian finds compare? I don’t know about you, but the discovery that dust on Mars is finer than previously thought or that water once may have flowed down its barren craters doesn’t bowl me over. Even the seas’ more obvious secrets are much richer -- for instance, sunken ships. Consider the Swedish warship Vasa, which sank in 1628. Raised in the 1960s, it now tells us things about where we came from, what life was like for our forebears and how far we’ve come.

Perhaps most important, the oceans are not merely the major part of our environment -- they are integral to its systems. They greatly affect the climate and the conditions that allow life as we know it to survive. And yet we have almost turned some seas -- the Mediterranean, for instance -- into garbage dumps. We need to study and measure the health of oceans because it is essential for our own well-being.

Those who believe that we can draw inspiration only from walking on the moon and not from diving into the oceans may be too young to remember the admiration with which many millions followed the explorations of Jacques Cousteau. All we need is a good race with other nations -- measured by how much ocean we cover and who can find more goodies faster -- and ocean exploration will be all the rage.

So let’s get going -- down, not up. If I had a car, its bumper sticker would read: “Blue yonder? Blue under!”