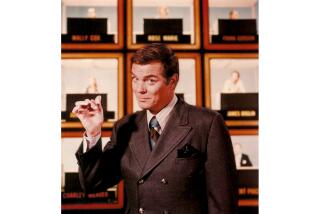

Jack Paar, 85; Blazed Talk Show Trail

- Share via

Jack Paar, who kept millions of Americans up past their bedtimes as the mercurial host of “The Tonight Show” in the late 1950s and early ‘60s and set the standard for the talk-show format with his eclectic mix of urbane and witty guests, died Tuesday. He was 85.

Paar, who had a stroke in March, died at his home in Greenwich, Conn., said Stephen Wells, his son-in-law. Paar’s wife, Miriam, and daughter, Randy, were by his side.

He was the original “King of Late Night.”

From 1957 to 1962, the onetime B-movie actor, stand-up comic and veteran of radio and daytime television ruled late-night TV in what originally was a live one hour and 45-minute weeknight broadcast -- from 11:15 p.m. to 1 a.m.

“I have little or no talent,” Paar once observed with a sly grin. “I can’t sing and I can’t dance, but I can be fascinating.”

Indeed, Paar was, by turns, charming, volatile and sentimental -- he was famously given to tearing up on camera, and had public feuds with variety show host Ed Sullivan (over the fees paid guest stars on their television programs) and newspaper columnists Walter Winchell and Dorothy Kilgallen.

Paar would tell humorous, self-deprecating anecdotes, often prefacing his stories of the unusual things that happened to him with his famous catch phrase, “I kid you not.”

And, like the neighbor next door, he’d talk about his wife and daughter -- so much so that after he was off the air a year, a cartoon caption read, “I seem to get along without Jack Paar, but I do wonder what happened to Miriam and Randy.”

But Paar was at his best chatting with his guests -- a colorful blend of actors, entertainers, writers, politicians and zanies -- in what he once likened to a “verbal barroom brawl.”

Among the more frequent visitors were the folksy raconteur Charley Weaver (played by comedian and pianist Cliff Arquette); the misanthropic artist-writer Alexander King; the rapier-witted pianist-composer Oscar Levant; the French chanteuse Genevieve; British actress Hermione Gingold; and the incomparable Jonathan Winters, who once walked on stage wearing a horned goat hat and clutching a small branch while announcing that he was the Voice of Spring.

Paar also welcomed politicians on the show, including separate appearances by 1960 presidential candidates John F. Kennedy and Richard M. Nixon.

But just as likely to drop by were the likes of James Thurber, Dorothy Parker, George S. Kaufman, the Rev. Billy Graham, Judy Garland, Beatrice Lillie -- and newcomers such as comedians Bob Newhart, Woody Allen and Dick Gregory.

“Jack was the beginning of talk,” said entertainer and entrepreneur Merv Griffin, a former Paar guest and substitute host who presided over his own talk show for 24 years. “Steve Allen preceded Jack with ‘The Tonight Show.’ That was more skits, man-on-the-street, music -- that kind of stuff -- and occasionally interviews, but not very deep.”

But Paar, Griffin said, “was the first to sit down and really have conversations. He made small talk huge.”

“The Tonight Show,” which eventually attracted a nightly audience of up to 8 million, became so successful that NBC renamed it “The Jack Paar Show.”

“There has never been anybody remotely like him, even though he influenced people,” said former talk-show host Dick Cavett, who was on Paar’s writing staff in the early 1960s. “Jack was just a meteoric talent.”

Anyone who watched Paar during his heyday, Cavett said, “realized you’re in touch with a quirky genius that you’re not in any danger of seeing anyone else like. It’s impossible to overestimate what he was on that show.”

What was said or done on Paar’s show frequently became water-cooler fodder the next day.

Griffin recalled the time Paar had Elsa Maxwell, the society arbiter and hostess, on as a guest.

“As she walked on, Jack said, ‘Elsa, you’re so perfectly dressed, but I hate to tell you, your stockings are wrinkled.’ She said, ‘I’m not wearing any.’

“All of us remember great moments with Jack.”

Many of those moments were featured in a 1997 “American Masters” tribute to Paar on PBS:

* Muhammad Ali (then Cassius Clay) reciting his poetry while Liberace accompanied him on piano.

* Paar mischievously shuffling the cue cards during a duet that paired Judy Garland and Robert Goulet.

* Paar asking Levant, a notorious neurotic and hypochondriac, what he did for exercise -- and Levant replying, “I stumble and then I fall into a coma.”

* Richard Burton recalling performing “Hamlet” on stage while Winston Churchill sat in the front row audibly reciting the lines along with Burton.

But Paar also got out of his New York studio, taking viewers with him on filmed visits to Africa to meet medical missionary Albert Schweitzer, to Cuba for an interview with Fidel Castro, to Hawaii to visit a leprosarium and to Germany to see the newly built Berlin Wall.

Washington Post TV critic Tom Shales once described Paar as a “raconteur, world traveler, virtuoso conversationalist and wicked wit. He was sort of a cross between Lowell Thomas and Noel Coward.”

“Jack Paar was so good,” Shales wrote, “he seemed to be in color when TV was still in black-and-white.”

What kept viewers tuning in was Paar’s unpredictability. One Hollywood star showed up on the show so inebriated that Paar asked him to leave. And it wasn’t unheard of for Paar to insult or even ignore a guest who said or did something not to his liking.

“It’s the only show where you watch the interviews and hope they’ll postpone the entertainment,” comedian Joey Bishop, a frequent Paar guest, told TV Guide in 1962. “You don’t know what stunning thing will build up out of the talk.”

Indeed, Newsweek magazine called the Paar show “Russian roulette with commercials.”

That was never more true than in 1960, when the NBC censor cut Paar’s humorous story dealing with a British couple who wanted to rent a cottage and the Swedish real estate agent’s confusion over the letters W.C. -- the common British abbreviation for a water closet, which the agent assumed to mean wayside chapel.

By then, the show was being taped earlier in the evening and the network censor cut the nearly five-minute story without informing Paar.

Paar, concerned that the censored joke made viewers think he had committed a “terrible obscenity,” stunned his audience -- and announcer Hugh Downs -- the next night by walking off the show.

“I’m leaving ‘The Tonight Show,’ ” an emotional Paar told his audience. “There must be a better way to make a living.”

About four weeks later, after making peace with NBC, Paar was back in front of the cameras: “As I was saying before I was interrupted

The audience greeted his return with rousing applause.

“Everybody has a go at trying to describe what his magic was,” Cavett said. “Jack used to have a saying, ‘This thing is all a personality contest.’ He’d say that sort of contemptuously, but in his case it was certainly true. He had a mercurial, magical, neurotic, dangerous something or other in him that made it impossible to watch anybody else on the screen with Jack.”

Winters said Tuesday that he “had a lot of good times with him” on the show, but added that Paar was “a very complicated guy” who “ran hot and cold.”

“He had a very short fuse, and when you were rolling he might very well stop you in the middle of a roll and say, ‘OK, I’m tired of that now.’ Which stopped you dead in your tracks, and it would take a couple of seconds to pick up the stick again and go.”

Despite his continued popularity, Paar grew tired of the grind and quit his late-night show in March 1962. That October, after a succession of interim hosts, Johnny Carson began his 30-year run as host of “The Tonight Show.”

“We all admired Jack,” said Griffin, who began his own talk show the same time as Carson. “Everybody who came out of talk shows realized he was the root of talk shows, and his form continued on through every talk show, which was the desk, the chair and the couch. I admit I copied my show right after him and, of course, Carson did too.”

In a comment carried by the Associated Press on Tuesday, Carson said he was “very saddened” to hear of Paar’s death. “He was a unique personality who brought a new dimension to late-night television.”

And current “Tonight Show” host Jay Leno issued a statement Tuesday noting that “Jack set the bar, and he set it very high. I was fortunate enough to have him as a guest on the show. He will be sorely missed.”

For a man who made his living talking in front of an audience, Paar was fundamentally shy.

Nervousness, Paar told the New York Times in 1991, caused him to pace, mumble to himself and wash his hands compulsively. And, he conceded, his opening monologue, which he memorized by writing it over and over in longhand, remained an ordeal.

“He was just on the edge all the time,” said Griffin, recalling walking down the hallway with Paar before an appearance one night when Paar said, “See that guy leaning over the piano? He’s been following me for weeks now. I see him everywhere.”

“Jack, it’s your saxophone player!” Griffin replied. “He’s been with you for three years.”

Paar, Griffin said, “had that edgy paranoia that was just fascinating to an audience. That was his key. He was so volatile. You never knew when he was going to blow up, cry or go after a guest.”

Cavett feels he knew Paar as well as anybody.

“Nobody who knew Jack -- even those who knew him in the Army days -- ever pretended to have the key to Jack or to be able to predict what he might do when he got off the elevator that day for work,” Cavett said. “In a way, it was almost like having an alcoholic parent: Each day it was, ‘How is he today?’

“It must have taken a tremendous toll on Jack’s nerves to be that ratcheted up and high-strung, but it just made a personality that burst through the screen.”

For his part, Paar in later years acknowledged that he was the same on and off the air. At heart, he was a talker.

The son of a New York Central Railroad division superintendent, Paar was born May 1, 1918, in Canton, Ohio.

Growing up in Canton and later Detroit and Jackson, Mich., Paar stuttered badly. In an attempt to cure his childhood stuttering, he’d close his bedroom door and put buttons in his mouth and practice reading aloud. His speech gradually improved.

At 14, Paar contracted tuberculosis and was bedridden for eight months. His father, who built radios as a hobby, installed a bedside workbench for him and taught him about radio, electronics and carpentry -- lifelong fascinations for Paar. After he was cured, Paar joined a railroad gang during the winter to toughen up, and he wrestled in high school.

But at 16, he dropped out of school after landing a job announcing the station breaks at a local radio station. A succession of other radio jobs throughout the Midwest followed.

Displaying a flair for humor, Paar eventually became a comic disc jockey. He was fired from one station for making a sarcastic comment after the owner announced there would be no Christmas bonuses.

In 1942, Paar volunteered for the Army and was assigned to the 28th Special Service Company, which provided camp entertainment directors. He met Miriam Wagner, who was related to the Hershey chocolate family, at a dance. They were married in October 1943, before Paar shipped out to the South Pacific. Jose Melis, an Army buddy, who became his “Tonight Show” musical director, played the organ at the ceremony.

In the South Pacific, Paar made a name for himself as an irreverent camp-show comedian who fearlessly ridiculed the enlisted man’s favorite targets: officers.

War correspondent Sidney Carroll caught up with Paar’s act in New Caledonia and Esquire magazine ran Carroll’s article on the brash young soldier. The story reported such nuggets as Paar telling an officer who insisted on talking during one show, “Lieutenant, a man with your IQ should have a low voice, too.”

As a result of the Esquire article, Paar was offered a contract with RKO after getting out of the Army in 1946.

A year later, he received his first big break in radio as summer replacement for comedian Jack Benny. He later substituted for Eddie Cantor on “Take It or Leave It” and for Don McNeill on the “Breakfast Club,” but his career in radio never really took off. Radio comedian Fred Allen referred to Paar at the time as “that guy who made a meteoric disappearance.”

Paar’s movie career was even less lustrous. He wound up playing minor roles in just five films, including “Love Nest,” a 1951 comedy with a newcomer named Marilyn Monroe.

Work in television followed, including “Up to Paar,” a short-lived NBC quiz show in 1951. He also hosted a couple of other TV game shows and, in 1954, co-hosted CBS’ “The Morning Show,” an entertainment-oriented show that failed to attract enough sponsors. That was followed by his hosting a little-watched half-hour weekday afternoon show on CBS.

Then, in 1957, came “The Tonight Show.”

After leaving late-night TV in 1962, Paar returned to NBC that fall with an hourlong prime-time Friday night talk-variety show, “The Jack Paar Program.”

But after three years, he left the show and, not yet 50, retired from the airwaves.

Except for a few specials and a short-lived TV comeback in 1973 -- a once-a-month 90-minute talk-variety show on ABC called “Jack Paar Tonight” -- Paar was content spending time with his family and friends, traveling, painting, playing tennis and puttering in his home workshop.

“It was not like some performers, for whom the spotlight is like oxygen is to you and me,” Downs told AP in 1997. “He didn’t really care that much about being on the air.”

Cavett had Paar on as a guest on his late-night ABC talk show twice.

“He was just smashing from the first word out of his mouth to the end of the 90 minutes both times,” Cavett recalled. “It was just a lesson in something that can’t be learned. He was hilarious.”

Paar made only sporadic public appearances in recent years. On those rare occasions, he’d tell young people in the audience, “I’m the fellow who used to entertain your mothers and fathers late at night. Obviously, I didn’t do a very good job, or you wouldn’t be here.”

In addition to his wife and daughter, Paar is survived by a grandson.

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.