Argentine Ceremonies Cast Light on ‘Dirty War’

- Share via

BUENOS AIRES — Four angry generals, five miffed governors and a pair of missing oil paintings were not enough to prevent President Nestor Kirchner from commemorating the dead of Argentina’s “dirty war” with two powerfully symbolic acts Wednesday that hit hard at the legacy of the country’s former military dictators.

Kirchner dedicated the Museum of Memory at the Navy Mechanics School, former site of a concentration camp where thousands of prisoners were tortured and murdered from 1976 to 1983 under military rule.

“I come to ask for forgiveness on behalf of the state for the shame of having remained silent about these atrocities during 20 years of democracy,” Kirchner said at a rally outside the school. “And to those who committed these macabre and sinister acts, now we can call you what you are by name: You are assassins who have been repudiated by the people.”

Hours before the dedication ceremony, four generals resigned in protest against Kirchner’s decision to remove the portraits of two former junta members from the National Military College on Wednesday, the 28th anniversary of the coup.

Jorge Rafael Videla and Reynaldo Bignone were among the most notorious leaders of one of the most bloody regimes in Latin American history. On Wednesday morning, the current head of the army, Gen. Roberto Bendini, climbed a small ladder to remove their portraits from a wall in the college’s Hall of Honor.

“Never again can we allow constitutional order to be subverted in Argentina,” Kirchner said at a separate ceremony at the college. “It is the people of Argentina, with their vote, who will define the destiny of Argentina.”

About 13,000 people were killed by military and paramilitary forces whose war against a small number of leftists quickly became a widespread purge against all forms of dissent.

For more than 20 years, Argentina’s democratically elected governments resisted probing too deeply into the past. And in the days before Wednesday’s commemorative acts, there were several indications that the issue remains divisive.

Military sources said the original oil paintings of the two junta leaders had been removed days earlier, a small act of defiance against the president’s desire to commemorate the crimes of the past. The missing oil paintings were replaced with framed photographs in time for Wednesday’s ceremony.

Also, five governors from Kirchner’s Peronist party reacted angrily to being excluded from the dedication ceremony at the Museum of Memory. Relatives of the dead had objected to their presence, saying the politicians were responsible for human rights violations in their provinces.

“If they [the governors] go, we won’t be there,” said Hebe de Bonafini, a leader of the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, a group of relatives of the slain and disappeared. There is a widespread belief here that some provincial police forces have been complicit in kidnappings, extortion and other crimes.

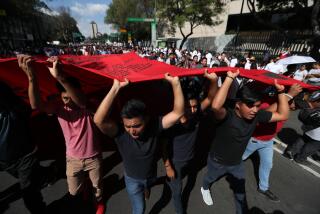

But, for the most part Wednesday, the focus was on the crimes committed a generation ago by the military regime in the name of order and anticommunism. The iron fence around the Navy Mechanics School was adorned the names and photographs of the dead.

Among those who spoke at a rally outside the Museum of Memory were two young people who were born at a maternity ward the military regime set up inside the concentration camp. Female prisoners gave birth there before being slain; their children later were given up for adoption, often to families of military officers.

“This place still contains the horrors of the past,” said Maria Isabel Greco, 26, whose mother was kidnapped in early 1978 and later killed. “But it also contains the love of the people who died here, the people who died loving their country, and who died loving us, their children.”

Times staff writer Andres D’Alessandro contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.