In Iraq, Army of Private Contractors Is Set to Stay Entrenched

- Share via

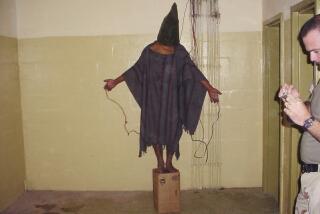

Judging from the headlines, not to mention the photographs, the outlook would seem ominous for U.S. contractors that provide support services to the military in Iraq.

In March, four men working for Blackwater Security Consulting were killed in Fallouja, their charred bodies dragged through the city before at least two were hung from a bridge over the Euphrates River. More recently, employees of Titan Corp. and CACI International have been identified as taking part in the horror show at Abu Ghraib prison.

In turn, some members of Congress are up in arms. Lawmakers are demanding greater oversight of private companies operating in Iraq. Some are threatening legislation that would prohibit contractors from working as interrogators, for example.

In general, Sen. Charles E. Schumer (D.-N.Y.) asserted Friday, “private contractors should be the last resort -- not the first.”

Yet the senator’s rhetoric notwithstanding, the use of private companies to handle tasks that once were the province of the armed forces is likely to grow in the months and years ahead. As Iraqis assume increasing responsibility for policing their own country, U.S. companies plan to play a large and profitable role in the process, training and assisting the locals.

This is especially true, given that (at least right now) there is a dearth of other countries willing to commit troops to the effort, leaving a wide-open field for American industry to play upon.

“U.N. peacekeepers would do some of this work if they had been involved here,” says Deborah Avant, a professor of political science at George Washington University.

Already, there are at least 20,000 private-contractor employees serving the military in Iraq. These folks -- who provide security for convoys of food and supplies, maintain vehicles and weapons, guard U.S. officials and translate Arabic to English -- stand in addition to the legions of private-sector workers who are undertaking the actual reconstruction of Iraqi ports, pipelines and other facilities.

Experts figure that expenditures for such support services could be running as much as $12 billion a year -- and the number is sure to increase with the Pentagon facing very limited options for adding more military personnel in the region.

“As a practical matter,” says Peter Singer, a national security expert at the Brookings Institution in Washington, “contracting will boom.”

The work is lucrative, affording salaries that average one-third more than comparable pay in the uniformed military. Indeed, the Pentagon’s goal isn’t to save money. It is to be able to concentrate on “core competencies -- training for and making war,” says Loren Thompson, director of the Lexington Institute, an Arlington, Va., firm that does consulting work for the Defense Department.

Such assignments aren’t for the timid, of course. Estimates are that 40 workers from private companies have been killed in Iraq in the last year. Three hundred contract employees have been wounded.

This bloodshed, coupled with the prison abuse scandal, has drawn fresh attention to private military contracting. But it is not a new trade. In 1990, at the end of the Cold War, the military stepped up its outsourcing of routine services such as food preparation, relieving soldiers of traditional KP (kitchen patrol) duty. Before long, more sensitive tasks such as managing information technology were privatized too.

Some suggest that things have gone too far, with private companies now performing “mission critical” functions, such as providing armed muscle for L. Paul Bremer III, the top U.S. civilian administrator in Iraq.

“I think we’ve crossed the line,” says Lawrence J. Korb, an assistant secretary of defense in the Reagan administration.

He raises a host of tricky issues: The armed forces are under military law, but private employees are not. Soldiers are expected to dig in and fight until they receive orders indicating otherwise. “Private employees,” Korb points out, “can walk away from dangerous duty.” In the end, then, how much control does a military commander really have over his battle zone?

For all these concerns, though, the bottom line is that there will be no major shift from using contractors. With U.S. forces stretched thin -- the active military has shrunk to about 1.4 million troops from 2 million in 1990 -- there is nowhere to turn but to private industry.

And so it is that two companies with Southern California connections -- Vinnell Inc., a subsidiary of Northrop Grumman Corp., and Computer Sciences Corp.’s DynCorp unit -- are training army and police forces in Iraq under contracts from the Defense and State departments.

Inter-Con Security Systems Inc., a Pasadena firm, is also headed to the Middle East with a contract from the State Department. Its aim: to train specialized Iraqi security forces on how to protect local power plants and electric grids.

Meanwhile, the MPRI division of L-3 Communications Holdings Inc. is competing for the renewal of the translation contract held by San Diego-based Titan, which has a deal to be acquired by Lockheed Martin Corp..

Out of this flurry of activity, one thing is clear: For better or worse -- or maybe both -- the private military is here to stay.

*

James Flanigan can be reached at jim.flanigan@latimes.com. For previous columns, go to latimes.com/flanigan

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.