In Italy, Being a Jailed Hit Man Has Its Perks

- Share via

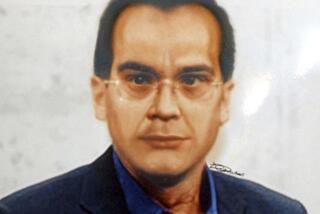

ROME — As mobsters go, Giovanni “The Butcher” Brusca makes Tony Soprano look like Snow White.

Among the 100 murders that Brusca has claimed to have committed are two of the most heinous crimes in Italian lore: the bombing assassination of crusading anti-Mafia prosecutor Giovanni Falcone, and the strangulation death of an 11-year-old boy, whose body was then dissolved in acid.

So the news this week that Brusca, imprisoned since 1996, is getting occasional time out for good behavior has created a storm of protest and revived questions about a controversial Italian law that gives breaks and perks to Mafiosi who turn state’s evidence.

Justice Minister Roberto Castelli, saying he was “outraged,” ordered an investigation. Other politicians from the ruling right and the opposition left said Brusca’s furloughs were absurd and a perversion of the judicial system.

Newspapers from Brusca’s home region of Sicily reported this week that a court last spring ruled that the former crime boss could be let out of prison periodically to spend time with his family. He is spirited to a secret location once every 45 days, the reports said.

His lawyer, Luigi Li Gotti, confirmed that Brusca had been allowed out of jail but insisted that his freedom wasn’t all it’s cracked up to be.

“The benefits he gets do not involve days of fun and swimming in the pool,” Li Gotti told Italian news agency ANSA. He doesn’t get free use of a telephone, for example.

The 47-year-old Brusca is most infamous for the 1992 murder of prosecutor Falcone. It was Brusca who pushed the remote-control button that detonated the bomb on a Sicilian highway as Falcone drove past. The prosecutor, his wife and three bodyguards were killed.

And then there was the vendetta slaying of Giuseppe Di Matteo, whom Brusca strangled and dissolved in acid. The 11-year-old was the son of a rival Mafioso who had become an informer.

Later, after his arrest, Brusca himself became a snitch and informed on his colleagues as part of Italy’s so-called turncoat law, which allows leniency for gangsters who cooperate with authorities. In exchange, he was sentenced to 26 years in prison instead of a life term for killing Falcone.

The same 1991 law is being used to grant Brusca his periodic outings from jail.

Prosecutors credit the law with the arrests of major gangland figures during the last decade. The testimony of turncoats has sent hundreds of mobsters to prison.

Critics, however, have long complained that wily criminals lie and otherwise abuse the law, which also gives some informants huge amounts of cash and refuge in a witness-protection program. Many return to crime.

The loudest protest this week came from families of Brusca’s victims.

“Someone who should have gotten 100 life sentences is already getting a concession with 20 years,” Falcone’s sister, Maria, said in a statement. “But the sentence must be served in prison.”

Falcone’s successor in the Sicilian capital of Palermo, prosecutor Piero Grasso, declined to comment on Brusca’s case. But he defended the law, saying that without incentives to turncoats, authorities would not be able to crack down on organized crime.

“Collaborators constitute an inalienable instrument for uncovering the secret structure of the Mafia organization,” Grasso told reporters.

“Even in the United States, collaborators are given immunity.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.