Turning Your Life Into Bits, Indexed

- Share via

‘I think we’ve got the Memex dream down,” Gordon Bell told me when I greeted him at Microsoft Corp.’s downtown San Francisco laboratory.

To technology aficionados his allusion would be instantly recognizable. “Memex” was a machine envisioned by Vannevar Bush, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s science advisor, in a prophetic 1945 Atlantic Monthly article titled, “As We May Think.” The device was an intriguing preconception of today’s personal computer in which, as Bush wrote, “an individual stores all his books, records, and communications” for easy retrieval through a form of indexing based on the associative properties of the human mind.

Bell’s version, embodied in a system known as MyLifeBits (soon to be formally renamed “Memex”) aims at nothing less than creating a digital archive of a person’s entire life.

The effort is not as much of a technical challenge as it sounds. It merely exploits two modern phenomena: the digitization of information and the plummeting cost of digital storage. Documents, snapshots, telephone conversations, music and home movies are now constituted from digital bits rather than ink on paper, chemical emulsions or analog waves.

The cost of storing all this material is minuscule and falling fast. Bell and his research associate, Jim Gemmell, estimate that a person’s entire lifetime production of paperwork, phone conversations and sounds and images can fit on a one-terabyte hard disk; that’s only eight times the size of the 120-gigabyte drive often found inside today’s medium-sized PC, and can be had for about $800, retail.

Bell, 70, is a distinguished engineer revered within the fraternity of computer scientists as a genuine pioneer. A cheerful, informal personality, he was the lead architect of whole families of groundbreaking 1960s-era minicomputers at Digital Equipment Corp. After leaving DEC and spending a few years running a National Science Foundation program and investing in start-ups, he joined Microsoft Research’s Bay Area lab in 1995.

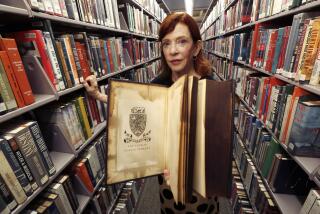

He had been pondering the digitization and storage cost curves for some time, but action was forced upon him a few years ago when he received a shipment of his old DEC papers from the company’s successor, Compaq. He solved the resulting storage crisis by scanning his books and papers into a computer, where the texts could theoretically reside, compactly, for eternity.

MyLifeBits took off from there. “We scanned every piece of paper he owned,” recalls Gemmell, 40. Then they moved onto photos and CDs, even the designs of promotional coffee mugs and T-shirts issued by companies Bell had founded or financed. When the process ended, virtually the only remaining physical objects were those with a sort of totemic significance, such as diplomas and award certificates. These went into a big black leather album.

The digital archive came to about 16 gigabytes, tiny in computer storage terms. Gemmell and Bell next considered how to retrieve items from this digital shoebox. The real achievement of their project is an indexing system that embodies Bush’s ideas about mental associations by cross-referencing each object with its various properties.

A photo shot by a digital camera, for example, might be linked to an address-book entry for a person in the photo, to a dot on a map showing where it was taken and a calendar showing where and when, and to written or spoken annotations. A user trying to recover the photo could track it down via any or all of those paths. (“All I remember is that I took it at lunch on July 5 in Yosemite ... “)

Gemmell showed me how this works on his office computer. He brought up a map of Southern California. A sinewy blue line began to trace the route he had taken on a family drive (including a meandering loop or two), based on continuous readings from his GPS device. Red dots appeared at various points, signifying locations where he had shot a photo.

Once the bare bones of a retrieval system were in place, Bell’s digital storeroom expanded from legacy material like technical articles, books, photos and videotapes to real-time recordings of his daily life -- conversations, phone calls, computer keystrokes, even his temperature and pulse rate.

Microsoft’s British lab contributed a device called the SenseCam, which hangs on a neck lanyard and snaps a low-resolution picture of one’s environment every few minutes. (Bell tested it for a few hours a day.) A new version also will record ambient audio and one’s location via GPS. The device will allow the user to play back an entire day -- 16 hours of wakefulness compressed into 1,000 photos -- in minutes.

By this May, the archive held 206,000 items in 101 gigabytes, including 84,300 e-mail texts, copies of 53,400 Web pages Bell had visited, 38,600 pictures and more than 15,000 documents. It grows at a pace of about 1 gigabyte per month.

The assiduous archiving of every aspect of personal experience may seem wacky to people today, who have enough trouble culling their family snapshots. But the idea has taken hold among computer engineers: A sold-out 2004 workshop Gemmell organized on what is now known as CARPE, for “Continuous Archival and Retrieval of Personal Experiences,” started participants thinking ahead to its social and legal implications. “Can we avoid subpoenas of a person’s digital memory?” Gemmell asks.

Bell and Gemmell have tried, thus far unsuccessfully, to interest neuroscientists in applying MyLifeBits for patients with memory loss, such as victims of Alzheimer’s. The idea may yet be too novel.

But they are convinced that the passive automated recording of one’s life is too logical, and will be too easy, to resist. “It’s like bucking the trend toward literacy,” says Gemmell. “That reduced our ability to remember things orally, but gave us the permanency of books.”

Bell, for his part, remains deeply committed to ferreting out and archiving all those records of his life still resisting his digital grasp. “I’m on a crusade right now to get all my EKGs,” he says.

*

Golden State appears every Monday and Thursday. You can reach Michael Hiltzik at golden.state@latimes.com and read his previous columns at latimes.com/hiltzik.