Vernon Ingram, 82; Biochemist Found Sickle Cell Anemia’s Cause

- Share via

In the quiet of a laboratory on the campus of England’s Cambridge University, biochemist Vernon M. Ingram made a discovery in 1957 that would prove to be a groundbreaking moment in the history of molecular medicine and sickle cell research.

Building on the work of Nobel Prize-winning chemist Linus Pauling, Ingram compared the hemoglobin of a normal red blood cell to the hemoglobin of a sickle cell.

Using a technique that he developed, Ingram discovered one small, but hugely meaningful difference: An amino acid found in normal hemoglobin cells was replaced with a different amino acid in the sickle cell. That one substitution caused a normal cell to take on the shape of a sickle, or crescent.

“What that did is create a tremendous amount of attention and hope in the area of sickle cell disease,” said Dr. Charles M. Peterson, director of the Division of Blood Diseases and Blood Resources at the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. “It led to the kind of momentum that generated the 1972 Sickle Cell Anemia Act.”

Ingram, a Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor who joined that university’s faculty in 1958 and was known to some as the “father of molecular medicine,” died Aug. 17 from injuries suffered in a fall. He was 82.

In recent years Ingram’s work focused on neuroscience, including Alzheimer’s disease. But he was most known for his 1950s discovery and its effect on the search for a cure or treatment for sickle cell anemia.

“In terms of really getting to a cure or a taking away of the horrible pain sequences that come with sickle cell disease, we’re probably halfway there,” Peterson said in an interview with The Times. “But Ingram and Pauling’s contributions in terms of mobilizing science for the public good just can’t be underestimated.”

MIT biology professor Graham Walker called Ingram’s discovery “one of the absolutely seminal discoveries in the history of molecular biology.”

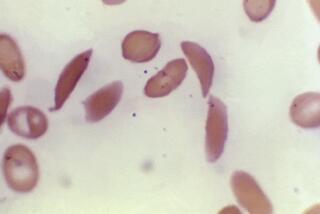

Sickle cell anemia is an inherited blood disease characterized by the presence of sickle-shaped red blood cells. Normal red blood cells are disc-shaped and concave. The sickle cells tend to clump together and obstruct blood flow. The result is an episode of extreme pain for a person with the illness. Damage to tissue and organs also occurs.

Nationwide, sickle cell anemia affects an estimated 72,000 people. About one in 12 African Americans has the sickle cell trait, or the gene that can cause the disease, according to estimates of the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, a part of the National Institutes of Health.

When Ingram began his work, researchers knew that the disease stemmed from a defect in hemoglobin, a protein inside oxygen-carrying red blood cells. In 1949 Pauling determined that the hemoglobin of sickle cells had a different electrical charge than the hemoglobin of healthy cells. He then made a conjecture that the charge was different because of a single amino acid substitution.

In 1952 Ingram turned his attention to sickle cell hemoglobin, urged on by Francis Crick, one of the discoverers of the double-helix structure of DNA in 1953.

Ingram developed a technique known as fingerprinting that mapped the amino acids in a protein. He compared the fingerprints of hemoglobin from a normal cell with the fingerprints of hemoglobin from a sickle cell and found a difference in their amino acid sequences.

In 1957 Ingram demonstrated that the difference was one amino acid. Normal hemoglobin includes glutamic acid. Sickle cell hemoglobin substitutes valine.

“It is astounding that the difference in structure is so small -- only about a dozen atoms out of 10,000 in the molecule are different,” Pauling said in 1958, commenting on Ingram’s findings.

Ingram’s discovery proved Pauling’s hypothesis correct, Peterson said, “and led to the whole explosion in molecular biology, looking for difference in protein structure to account for disease.”

The finding, an important link in understanding the disease, also helped increase research, public awareness of and funding for sickle cell disease. The 1972 Sickle Cell Anemia Control Act provided funding for the establishment of sickle cell anemia screening and counseling programs, research and training. The National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute was given the responsibility of developing and supporting a national sickle cell anemia program.

“In 1972 the average lifespan for a person with sickle cell disease was probably in the mid to late teens,” Peterson said. “Now a person with sickle cell disease has a life expectancy of 50-plus.”

Ingram was born in Breslau, Germany, to a family that fled the Nazis and settled in England. At Birbeck College at the University of London, Ingram received a bachelor’s degree in chemistry in 1945 and a doctorate in organic chemistry in 1949.

For the next two years he worked in the United States at the Rockefeller Institute and studied peptide chemistry at Yale.

In 1958 Ingram joined the faculty at MIT for what was intended to be a one-year visit. “I liked it so much that I stayed,” Ingram told the National Academy of Sciences in 2002.

Most recently Ingram ran a small laboratory at MIT and was pursuing new research.

“He was a dyed-in-the-wool, inveterate experimentalist,” Walker said. “He was going at full speed right up until the end.”

Ingram’s survivors include his wife, Elizabeth; a son, Peter; and a daughter, Jennifer.