STEEL HORSE

- Share via

CLINTON, N.C. — A sign at Clinton High offers visitors a friendly warning. “Danger,” it reads, “you have entered Dark Horse Territory.”

It refers to the unusual nickname of the school’s athletic teams -- Dark Horse Stadium, home of the five-time Class AA state football champions, sits next to the sign.

But it could also refer to a graduate named Willie Parker.

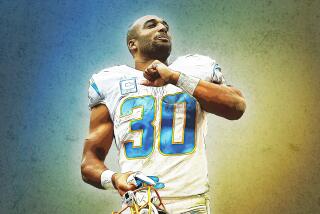

The Pittsburgh Steelers’ 5-foot-10, 209-pound running back is not the first player from this rural town of about 8,600 to have made it to the NFL, nor will he be the first to have played in the Super Bowl when the Steelers meet the Seattle Seahawks on Sunday at Detroit.

But he undoubtedly is the first to have raced a pit bull as a teen, caught the eye of an NFL owner’s son while still in high school, and all but disappeared in college before reemerging as an improbable 1,000-yard rusher for an AFC championship team.

A descendant of slaves who worked a farm not more than 10 miles from Clinton, Parker is the product of a blue-collar environment. Hog farming and hog processing drive the economy in Sampson County, and, when the wind blows just so, unsuspecting visitors had better brace themselves when stepping from their cars. Otherwise, the smell might knock them right off their feet.

Parker’s father, Willie Parker Sr., was a hog gambrel before a shoulder injury put him on disability. Day after day for 27 years, he lifted the 200- to 300-pound beasts onto hooks for butchering.

The youngest in his family of six had much grander plans.

“When he was 5 or 6, he stood in front of the TV and he’d say, ‘Me want to play for Carolina,’ ” his mother, Lorraine, said of the boy who did grow up to play for the Tar Heels. “I said, ‘Get out from in front of the TV and go sit down.’ And then when he was 10 or 11, he’d say, ‘Me going to play for the NFL.’

“I said, ‘If you don’t get your behind out from in front of that TV ... ‘ “

Parker got moving, all right.

Speed always set him apart.

One Thanksgiving, noting that a cousin’s pit full was so well-trained that when his owner whistled from across a field the dog would run toward him in a full sprint, Parker asked whether he could race it.

“The dog’s name was Tyson,” Willie Sr. said, “and Tyson would come full speed toward my nephew. And my son would try to beat the pit bull. It looked pretty good at the beginning, but the dog ran away from him.

“But he actually tried to beat that dog. He did it several times, and you could see from the muscles in his legs that he was giving it his all.”

Two-legged challengers posed less of a threat to Parker, who could step right out from the side door of the modest, three-bedroom house where he grew up and run for miles without ever encountering a car, much less a pit bull.

Across the street was a kid’s dream -- Royal Lane Park, an 80-acre recreational facility -- and that’s where Parker set about chasing his dream.

It didn’t seem unrealistic because of Clinton’s glorious tradition.

“This is a unique place as far as football,” said former Clinton High coach Bob Lewis, whose teams at various stops have won six state championships. “People love football. Friday night, the stands are packed full. You would think maybe you were in a place like Pennsylvania or Texas, that kind of environment.

“That’s the kind of environment Willie came up with; he was in the weight room working out with guys that had played in the NFL.”

Three other players coached by Lewis -- running backs Leonard Henry and Jerris McPhail and defensive tackle Ronnie Dixon -- played in the NFL. And Clinton grad Dennis Owens, who graduated before Lewis arrived, played nose guard for the New England Patriots in the 1986 Super Bowl.

“I can’t explain it, nobody can explain it,” Lewis said of Clinton’s fertile training ground. “It’s like these guys crawl out of the woodwork.”

Clinton won two state titles during Parker’s three varsity seasons, and by the time he signed with North Carolina after rushing for 1,801 yards as a senior in 1998, Lewis considered him a can’t-miss prospect, at least as gifted as the three dozen other players he had sent to Division I college programs.

A former North Carolina high school assistant -- Pittsburgh scout Dan Rooney Jr., son of the Steelers’ owner -- also thought highly of him. At the same time Parker was averaging more than 10 yards a carry as a high school star, Rooney lived for about 1 1/2 years in Clinton. His wife, a doctor, worked at the same clinic as the high school’s team physician.

Parker, though, never caught on at North Carolina.

The coach who signed him, Carl Torbush, was fired after Parker’s freshman season. And then, in August 2001, while Parker was in Chapel Hill preparing for his sophomore season, his best friend, Jamar “Marty” Smith, was gunned down in a drive-by shooting in Clinton.

“That just took something out of him,” his father said. “I mean, he cried, cried, cried. It took him awhile to get out of it, and by the time he decided he was going to get out of it, he’d done lost his position.”

Parker was nicknamed “the Clinton Bypass,” a reference to his supposed reluctance to run between the tackles. And the new Tar Heel coach, John Bunting, utilized him less each season. He didn’t play at all in his final game, against Duke on Senior Day in 2003.

“That was like a slap in my face,” Parker said Tuesday in Detroit. Of his overall experience at North Carolina, Parker said, “That was like a rainstorm, and I wasn’t prepared for that rainstorm coming out of high school. ...

“I won’t blame it all on the coaches. I take some of the blame myself. We just didn’t see eye to eye. It was just one of those situations where the coach is always going to be right and the player’s never right.

“They decided not to play me and I had to live with it.”

Whatever the reason for his disappearance at North Carolina -- he rushed for 1,172 yards in four seasons, only 181 in 48 carries as a senior -- Parker still believed that somehow, some way, he had a shot at reaching the NFL.

Undeterred, he returned to his roots at Royal Lane Park.

“He came home and just started running across those fields, training like he was going somewhere,” his mother said, gesturing across the road.

Interjected Willie Sr.: “I thought he was trying to kill himself. I even said something to him. He said, ‘It’s called getting prepared.’ ”

Parker wasn’t drafted, but Rooney remembered him, and, acting on a recommendation from the owner’s son, the Steelers signed him as a free agent.

As Lewis said last week, “That’s a heck of a connection.”

Rooney said that while living in Clinton he had naturally gravitated to the high school football games because they were such a big deal in the town.

And not only did he recommend Parker, he recruited him too, the scout calling Parker regularly in the days and weeks after his final game at North Carolina to tell him that the Steelers were still interested.

“It was just a matter of taking a guy with speed,” said Rooney, who now lives upstate in Gastonia. “And I knew coming from a serious high school program that he wouldn’t quit, that he’d keep driving. Willie took it from there.”

A rookie last season, Parker was inactive for nine of the Steelers’ 18 games, including both playoff games. He carried only 13 times in eight other games. But in the regular-season finale, with Coach Bill Cowher resting most of his starters for the playoffs, the former Dark Horse from Clinton announced his arrival with 102 yards in 19 carries against the Buffalo Bills.

And when injuries sidelined Duce Staley and Jerome Bettis in training camp last summer, Parker moved into the starting lineup and never left.

Bringing a “home run threat every time” to the usually more power-oriented Steelers, as teammate and receiver Hines Ward put it, the fast-moving Parker ran for 161 yards in the opener against the Tennessee Titans and 111 in Week 2 against the Houston Texans.

By regular season’s end last month, he had turned in three more 100-yard efforts and rushed for 1,202 yards, making him the sixth 1,000-yard rusher in Steeler history and the first since Bettis in 2001.

He carried 255 times, only 30 fewer than he had in four seasons at North Carolina, and averaged 4.7 yards -- fifth in the NFL for backs with at least 200 carries, behind Shaun Alexander of the Seahawks, Tiki Barber of the New York Giants and Larry Johnson of the Kansas City Chiefs, the league’s top three rushers, and Warrick Dunn of the Atlanta Falcons.

He had nine runs of 20 yards or longer, Cowher telling reporters that Parker’s speed brought to the Steelers, “the one thing that we never had.”

Said Rooney: “He’s a real good kid. It’s been nice to watch.”

Sunday, he and Clinton will watch Parker in the Super Bowl.

“I don’t have the words just yet,” Parker’s father said. “Is this really happening? I never thought that that little bad boy would be playing in the Super Bowl. He was just a little picky fellow, you know what I’m saying?

“It’s a great feeling. I’m good and proud of him.”

*

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX)

Fast company

Pittsburgh second-year running back Willie Parker finished the regular season with 1,202 yards rushing, and his 4.7 yards per rush ranked him fifth in the NFL for those with a minimum of 250 carries:

*--* PLAYER, TEAM YPC ATT YDS Tiki Barber, N.Y. Giants 5.2 357 1,860 Larry Johnson, Kansas City 5.2 336 1,750 Shaun Alexander, Seattle 5.1 370 1,880 Warrick Dunn, Atlanta 5.1 280 1,416 Willie Parker, Pittsburgh 4.7 255 1,202 Clinton Portis, Washington 4.3 352 1,516 L. Tomlinson, San Diego 4.3 339 1,462 Rudi Johnson, Cincinnati 4.3 337 1,458 Thomas Jones, Chicago 4.3 314 1,335 E. James, Indianapolis 4.2 360 1,506

*--*

Source: NFL.com

*

Clinton, N.C.

Population: 8,600 (2000 census).

* Area: 7.1 square miles.

* Median annual household income (2000): $25,904.

* Median home value (2000): $78,700.

* Nearest big city: Raleigh, N.C., 60 miles northwest.

* Best known for: Hog farming. An 800,000-square-foot processing plant in town employs about 1,200 and annually processes more than 9.1 million hogs.

* Fun fact: Terry Holland, who coached Ralph Sampson at Virginia, is a Clinton High alumnus, as are Leonard Henry, Jerris McPhail, Ronnie Dixon and Dennis Owens -- all former NFL players.

*

THE SERIES: For glitz, glamour and overkill, perhaps no sporting event in the world can match the Super Bowl. But many of the game’s participants are products of humble, small-town environments far from the bright lights. Today is the second of four profiles - Willie Parker, Pittsburgh Steelers Running back from Clinton, N.C.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.