A Case That Tests Limits

- Share via

Not everyone was stunned by the news this week that follow-up testing had cleared Marion Jones of a potential doping violation.

While secondary results almost always confirm an initial positive, experts say that Jones fell into a category of difficult cases.

The sprinter was suspected of using an endurance booster called erythropoietin. The testing for EPO, which has evolved steadily in recent years, can be hard to interpret.

“Our sense is that it’s a very reliable test,” said Dick Pound, chairman of the World Anti-Doping Agency. “The trickiness is having enough experience in the particular lab that is conducting the test to know what they are seeing. You can get a difference of opinion.”

Travis Tygart, general counsel for the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency, which polices doping among American athletes, said his agency does not comment on active cases. A call to the UCLA Olympic Analytical Laboratory, where the tests were conducted, was not returned.

Meanwhile, some in the drug-testing business wondered about the viability of EPO tests.

“They’re applying the best technology available,” said David Black, head of a Nashville lab. “But the question remains, is it good enough?”

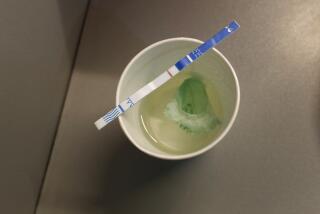

The Jones case began when she gave a urine sample at the U.S. championships in late June.

The 30-year-old sprinter had fallen on hard times after winning three gold medals and two bronze at the 2000 Sydney Olympics.

Her ex-husband C.J. Hunter and ex-boyfriend Tim Montgomery had been suspended for doping violations, and her former coach Trevor Graham had been sanctioned.

Jones also had been swept up in the BALCO scandal, confronted with allegations of steroid use, which she steadfastly denied.

The U.S. championships, where she won the 100 meters, were supposed to be part of a comeback.

Instead, news of her initial positive result joined a list of disturbing reports, allegations against Tour de France winner Floyd Landis and top male sprinter Justin Gatlin.

If found to have used EPO, Jones faced a two-year ban.

Under general protocol, urine samples are divided in two. If the “A” portion tests positive for a banned substance, officials cannot allege a violation unless the “B” portion provides confirmation.

With EPO, which increases the oxygen-carrying capacity of blood, the process is difficult because it involves a hormone that occurs naturally in the body. Testers are not looking for mere presence, but for evidence of EPO being introduced from an outside source.

“It’s a whole ‘nother step to look for things that are endogenous like testosterone or hormones like EPO,” said Tygart, speaking in general terms. “And EPO is a more complex molecule.”

The test can take several days, increasing the risk of human error in the lab. Results are more open to interpretation than with some other kinds of tests, experts said.

“Depending on your scientific point of view, you’re either more inclined to say, ‘It’s close but I think it’s positive,’ or you’re more inclined to say, ‘It’s close but I’m not confident enough to say it’s positive,’ ” Pound said.

This scenario was complicated by the fact that word of Jones’ positive “A” sample, supposed to be kept confidential, was leaked to the media.

“The leaking business is a nasty business,” said Steven Ungerleider, an Oregon researcher and anti-doping expert. “It’s destructive to every piece of the system, harmful to both the athletes and the testers.”

In the universe of drug testing, it is extremely rare for “A” and “B” results to conflict.

But at least two athletes -- including miler Bernard Lagat -- initially tested positive for EPO and were subsequently cleared.

Allen Murray, an Irvine biochemist, told the Chicago Tribune that he reviewed Jones’ “A” result and witnessed the testing of the “B” sample on her behalf. He said the initial positive result should have been thrown out because of unanswerable questions about the data it contained.

Pound said he was waiting for USADA and the UCLA lab to provide details of the testing.

As word of the negative “B” result spread Thursday -- made public by Jones’ attorneys -- the athlete said in a statement that she was “absolutely ecstatic.” Her manager told Reuters that she planned to resume competing at a World Cup in Athletics meet in Athens next week.

Anti-doping officials, meanwhile, found themselves on the defensive.

Tygart remained adamant about USADA’s continuing to support the EPO test and Pound, speaking by telephone from his office in Montreal, refused to view the situation as a defeat for drug testing.

“I think it shows the system works,” he said. “In close circumstances, the benefit of the doubt goes to the athlete. I think athletes should be delighted.”

Ungerleider, while suggesting that testers continue to police EPO use, called it a “reality check.”

“The technology is there,” he said. “But there are mistakes that can be made.”

*

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX)

Timeline

Marion Jones has battled doping allegations for years:

* Fall 2003: Jones is among several athletes to testify before a federal grand jury in San Francisco investigating BALCO.

* Dec. 7, 2004: The IOC opens an investigation into doping allegations against Jones after BALCO founder Victor Conte -- who served a four-month prison term for his role in the steroid scandal -- alleged he supplied her with an array of banned drugs before and after the Sydney Olympics.

* Aug. 18, 2006: Jones’ “A” sample tested positive for the banned endurance-boosting hormone EPO at the June U.S. track and field championships in Indianapolis, people familiar with the result tell the AP. For the next month, she is faced with the possibility of a two-year ban from the sport.

* Sept. 6, 2006: Jones’ backup, or “B” sample, is negative, her attorneys say. She is cleared of any wrongdoing and allowed to return to competition. “I am absolutely ecstatic,” she says.

Source: Associated Press

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.