Search for an E. coli defense

- Share via

Barbara and Mike Kowalcyk knew E. coli was a food-borne illness that could make people sick. But the Wisconsin couple were entirely unprepared for what they heard five years ago as their stricken 2-year-old son lay in a hospital bed nearby.

“The doctor sat my husband and I down in this little, tiny waiting room and said, ‘Mr. and Mrs. Kowalcyk, we are so sorry -- this is possibly the worst thing that can happen to your child. There is no treatment. There is no cure,’ ” Barbara Kowalcyk recalled last week. “I could not believe there was nothing they could do. It was horrific.”

Their son, Kevin, died of acute E. coli poisoning eight days later, and, true to the doctor’s word, there was very little anyone could do.

That could change.

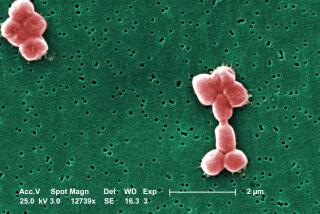

Part of the alarm over cases of E. coli poisoning, such as the current spinach-linked outbreak blamed on the 0 O157:H7 strain, has been the difficulty in treating the most severe cases -- when toxins produced by the bacterium cause kidney failure. But researchers have been working for two decades to learn more about the illness and now think they will eventually have ways to limit the damage.

“There is a tremendous urgency to find treatments,” says Dr. Howard Trachtman, a pediatric nephrologist and expert on E. coli at Long Island Jewish Medical Center in New Hyde Park, N.Y. “It’s a very serious disease. It affects previously healthy kids, and the morbidity is so high. Three to 5 percent die.”

The O157:H7 strain releases a toxin, called Shiga toxin, that attacks the intestines, causing bloody diarrhea and intense cramping. Sometimes the intestines bleed and break down. The toxin also can cause hemolytic uremic syndrome, in which the kidneys shut down due to damage in the small blood vessels. Both complications can be fatal, but kidney failure causes most E. coli-related deaths.

Doctors are essentially helpless to reverse hemolytic uremic syndrome once the process has begun, Trachtman says.

Instead, they try to keep the patient hydrated while providing electrolytes to maintain the body’s nutritional balance. Some patients need kidney dialysis, the use of a ventilator, blood transfusions and blood pressure medication to keep them alive while the body fights the infection and toxins.

With enough supportive care, most are able to pull through. The body’s immune system fights off the infection, and the kidneys are able to heal themselves. A few patients -- usually children and elderly people, who have weaker immune systems -- are unable to recover.

Most people fare best if they seek medical help quickly and are admitted to a hospital with expertise in treating hemolytic uremic syndrome, says Dr. Phillip Tarr, a professor of pediatrics at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. Tarr treated many of the children who fell ill in 1993 in the Pacific Northwest from E. coli poisoning involving contaminated, under-cooked meat. The O157:H7 strain was also blamed in that outbreak. Much of the current research focuses on intervening earlier in the biological process, before the kidneys fail.

Several research groups are trying to create antibodies to the Shiga toxin, substances that would recognize and help fight the poison.

“We’re making headway on therapeutics designed to neutralize the Shiga toxin,” says Tom Obrig, a professor of medicine at the University of Virginia and an expert on E. coli poisoning. “Some have been tested in animal models, and there are promising results for those.”

One company, Caprion Pharmaceuticals Inc. in Montreal, announced last week that its anti-toxin antibodies had been proved safe in 40 healthy adult volunteers. The company plans to conduct clinical trials on the drug, Shigamabs, next year.

“I think the antibody approach is the furthest along,” says Alison O’Brien, chair of microbiology and immunology at Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, a federal school of medicine and nursing in Bethesda, Md. “The belief is that if you give this early enough, you can neutralize the toxin,” meaning that the toxin could be inactivated while it is in the bloodstream so that it cannot attach to the cells.

Other researchers are trying to develop drugs that protect the kidneys from severe damage by reducing toxin-induced inflammation.

“The toxin damages the host cells in the kidney, but it does it in a way where we think we can intervene,” Obrig says. “The kidney damage doesn’t occur for several days after the bloody diarrhea. So there is this window of opportunity.”

Using standard anti-inflammatory drugs, such as aspirin, won’t limit damage to kidney cells caused by Shiga toxin, he says. However, researchers have identified a specific class of chemicals called adenosine-based compounds that appear to reduce inflammation in the kidneys and in other areas of the body.

Finding ways to reduce kidney inflammation is of growing importance for other conditions as well, says Dr. Joseph V. Bonventre, director of the renal division at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. Each year, thousands of people suffer acute kidney injuries due to a variety of causes, including infections, medications and blood pressure problems. Currently, there is little that can be done to limit this damage, he says, but many researchers think anti-inflammatory drugs for the kidney can be developed.

Doctors are also aiming to identify kidney damage at earlier stages, Bonventre says, using chemicals in the urine that signal dysfunction.

“Biomarkers in the urine could tell us when the kidney is in trouble,” he says. In the case of an acute E. coli poisoning, for example, ‘we’d be able to take children who have diarrhea -- and where there is some question of them being exposed to this type of bacteria -- and ask them for a urine sample. We could say, ‘OK, we think you’re in trouble. We want to bring you to the hospital.’ ”

Urine tests for biomarkers could become available in a few years, he says.

A vaccine could also be a possible weapon against E. coli poisoning. Children who are being immunized against other illnesses, such as diphtheria and tetanus, could get a vaccine that would also protect against Shiga toxin.

O’Brien’s research team recently announced that it had created a vaccine that successfully protected mice against developing hemolytic uremic syndrome when exposed to a Shiga toxin. It has not yet been tested in humans.

The most immediate advance may come in the form of better tests to identify E. coli O157:H7 infection, O’Brien says. Most toxin-detection tests take one day or longer to produce results. But a rapid-result test kit, which could reach the market next year, could more quickly determine which patients need intense treatment.

As for new medications to treat patients, researchers say they are mindful of the hurdles ahead. Although several animal studies have looked promising, no one knows how a drug or vaccine may work in humans. In 2003, scientists were disappointed when the first treatment for acute E. coli poisoning, a drug designed to bind to the toxin and absorb it, showed no benefit.

Moreover, because severe E. coli poisoning affects so few people, some health experts wonder whether a pharmaceutical company would be interested in commercial development of a drug or vaccine, O’Brien says.

However, Obrig notes E. coli O157:H7 is now listed on the nation’s select agent list of possible substances that could be used in bioterrorism attacks. That status, he says, could lead to more funding for research.

Despite the need for better treatment, Barbara Kowalcyk says the priority should be to eliminate the bacteria from the nation’s food supply. The couple believe their son was sickened by a hamburger, though proof was never found. The family now lives in Ohio, and Barbara Kowalcyk is president of a nonprofit consumer group that advocates for better food safety measures called Safe Tables Our Priority.

“I advocate completely looking for a cure,” she says. “But in the meantime, it’s really important to prevent it from getting to American tables in the first place.”

*