On a money trail to fix ailing schools

- Share via

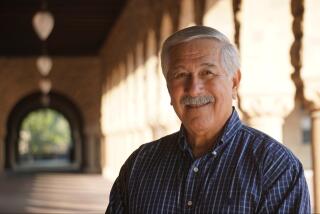

EDUCATION advocate Paul F. Cummins has always stood out among L.A. activists. A member of the Westside elite -- a former teacher at the Harvard School before it merged with Westlake, co-founder and former headmaster of the Crossroads School in Santa Monica -- his philosophy about education and virtually everything else is anything but elitist.

Though known for a signature private school and for championing charter schools, Cummins’ biggest passion is meaningful reform of public schools; like Jonathan Kozol, he staunchly believes that America cannot survive, let alone thrive, as a free and just society until and unless it takes the job of educating its young people seriously and in a manner commensurate with its immense wealth.

It doesn’t take an education expert to see that this has not happened. It’s also clear that the inequities in public schools are so long-standing as to now be conventional wisdom: urban schools are by definition poor, colored and failing, while suburban schools are affluent, white and successful. Not even the current school-reform fervor, with its loud pledges to uphold standards and excellence, does much to disturb this fact.

In his book, “Two Americas, Two Educations: Funding Quality Schools for All Students,” Cummins seeks to shock us out of our complacency by showing us the money. Most people assume that there is simply not enough money to fund schools adequately, let alone well; Cummins says that’s bunk. He says the real culprit is a gross, carefully maintained imbalance of money that, like the poor state of education, we’ve come to accept. Cummins argues that such a status quo is not only bad for underfunded schools, it’s bad for the health of democracy itself.

Yet Cummins doesn’t want to force the bitter medicine of reality down our throats so much as he wants us to get well. With an impressive array of facts and figures, plus sobering quips from writers and thinkers as varied as Thomas Friedman, J. Pierpont Morgan and Bill Moyers, he lays bare a tax system and pattern of government policies skewed so heavily in favor of big corporations and the rich that it’s a wonder public services function as well as they do.

Cummins feels that too many people are not contributing their fair share of taxes, that too much of that burden falls on the poor, and that the dollars we do collect are not properly prioritized. In a surprisingly brisk 168 pages, Cummins balances lots of mind-blowing but potentially eye-glazing data -- between 1983 and 1998, the top 15% of wage earners nabbed 90% of the increase of wealth and income, for example -- with his own sense of outrage.

He insists that what looks overwhelming and intractable is fixable; all we need to do is have everyone pay a proportionate amount of taxes, which Cummins believes should be based not simply on income but on how much business negatively affects the environment, public health and other things. Among the many solutions Cummins offers to ease the educational crisis and the equity crisis in general is a reformation of California’s property-tax capping Proposition 13, an overhaul of corporate welfare, a progressive Social Security tax and a “sin” tax on gun manufacturers, auto makers and other companies whose products are responsible for a disproportionate number of deaths and environmental destruction.

Of course, this all probably smacks as too much socialism not only to business hawks and conservatives but to ordinary Americans who aren’t necessarily either but who cling to the notion that the rich are bootstrap heroes who we can all theoretically become one day. Cummins understands this deep investment in the idea of Americanness -- he’s invested in it too.

He wants to make the point, as the book title suggests, that right now it is an idea divided against itself and that striving for equality and balance -- educational, racial, social -- is at least as American as self-aggrandizement and cheating on taxes. Yet even Cummins wonders, given all the grim stats, if he is foolish to expect change on the scale that it needs to happen. He decides that he has no choice but to stick to core beliefs about this country that have always guided him. “There is a fundamental decency and sense of justice in the American psyche, and in the long run these qualities lead Americans to sense and to do the right thing,” he writes. That may be socialist, but it’s also as old-school as it gets.

*

Erin Aubry Kaplan is a contributing editor to The Times’ Op-Ed pages and a former staff writer for LA Weekly.