3 win Nobel for gene work

- Share via

Two Americans and a Briton were awarded the 2007 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine Monday for their work in creating “designer mice” -- experimental animals in which genes have been added or removed to test theories about the links between genes and disease.

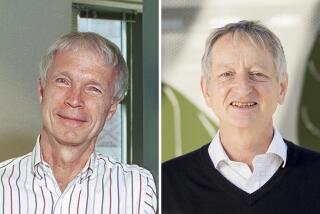

Mario R. Capecchi, 70, of the University of Utah; Oliver Smithies, 82, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; and Martin J. Evans, 66, of Cardiff University in Wales will share the $1.54-million prize for work that the Nobel committee said “has revolutionized life science and plays a key role in the development of medical therapy.”

Evans isolated embryonic stem cells from early mouse embryos, providing a tool that could be used to introduce new genes into mouse strains. He is widely considered to be the father of embryonic stem cell research. Researchers hope that such cells, which have the ability to turn into any other type of cell in the body, will eventually be useful in treating a host of diseases.

Capecchi and Smithies independently developed techniques to target individual genes within an organism and eliminate or replace them with a slightly altered form that could then be passed down to descendants.

The “knockout” mice, in which specific genes have been eliminated, allow researchers to demonstrate exactly what the gene does in a living organism. Smithies compared the idea to removing the steering wheel from a car to see what role it played in driving the vehicle.

Since the researchers reported their results in the 1980s, mouse strains have been produced in which about half of the mouse genomes’ 22,000 genes have been individually eliminated. Researchers expect all of the mouse genes to have received the treatment within the next few years.

The knockout mice also provide animal models for diseases, allowing researchers to test new drugs and treatments.

In 2001, the three scientists received the Albert Lasker Award for Basic Medical Research -- an award that is often assumed to be a precursor to the Nobel.

Jeremy Berg, director of the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, which funded most of Capecchi and Smithies’ research, said both awards were richly deserved because the men’s work had “dramatically reshaped the research landscape” and created “an indispensable tool for biomedical research.”

Ironically, the institute rejected Capecchi’s initial grant proposal, arguing that “the experiments would never work,” Capecchi said in a telephone interview. He used funds from other grants from the National Institutes of Health to validate his ideas.

“It was a gamble,” he said. “Fortunately, it succeeded.”

Capecchi’s life story is perhaps the most dramatic of any recent Nobel winner. Born in Verona, Italy, in 1937, he became a street urchin at age 4 when his mother was captured by the Nazis and carted off to the Dachau concentration camp. He survived on the streets and in orphanages throughout the war until he was reunited with his mother at age 9.

Mother and son then moved to the United States to live with his aunt and uncle, and he was enrolled in the third grade, even though he spoke no English.

When Capecchi got a 3 a.m. call from Sweden about the award, he said, it was “a very pleasant and wonderful surprise” that kicked off a day of celebrations. “The only thing that has kept me surviving is coffee.”

Smithies was born in Yorkshire, England, and educated at Oxford University before immigrating to the U.S. in the 1950s at the suggestion of his research supervisor Sandy Ogsten. “I wasn’t particularly keen on it,” but it worked out well, he said.

He said the Nobel financial reward was not as important as “the feeling that people appreciate the science you have done.”

“I’ve spent 50 years as a bench scientist, and the first paper [on the Nobel-winning research] came after I was 60 years old. It shows that . . . one shouldn’t be in a hurry to throw people out because they are old.”

Evans was visiting his daughter in Cambridge, England, when he received news of the prize. “I haven’t come to terms with it yet,” he told the Associated Press. “In many ways, it is the boyhood aspiration of science, isn’t it?”

He was knighted by Queen Elizabeth on Jan. 1, 2004, his 63rd birthday, for his contributions to medical science.

The trio will receive their awards Dec. 10 in Stockholm.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.