Designer melded emotion and utility

- Share via

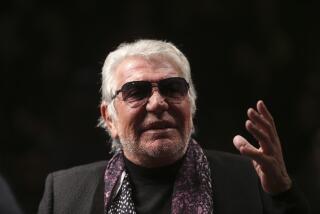

Ettore Sottsass Jr., the influential Italian designer and architect whose creations -- including the now-iconic red Olivetti portable typewriter -- were designed to change the perception of functional objects and enhance the experience of using them, died of heart failure Monday at his home in Milan, according to news reports. He was 90.

In the United States, Sottsass is known primarily as the patriarch of the Memphis Group, a collaborative whose provocative furniture creations in the early 1980s challenged the tenets of modern design.

But long before Memphis, Sottsass had earned a vaunted status with his philosophy that design should evoke an emotional response beyond function. That view led him to create works that critics described as full of poetry, personality and passion -- words that were not often linked with objects like typewriters or bookcases.

In a career that spanned 65 years, Sottsass produced a body of work -- furniture, jewelry, ceramics, glass, silver work, lighting, office machine design and buildings -- that defies easy categorization, yet has inspired generations of architects and designers.

In 2006 the Los Angeles County Museum of Art showcased the works of Sottsass in his first major museum survey exhibition in the United States.

“Basically what unites all his work . . . is that he was opposed to a rigidly ideological modernism,” said Wendy Kaplan, department head and curator of decorative arts and design at LACMA. “He advocated a playfulness, a design for delight. He would talk a lot about enhancing life, he would say things like, ‘Buildings affect the entire body.’ ”

For Sottsass, who was also a social critic, philosopher and poet, design was “a way of discussing life.” In his choice of materials, he was an egalitarian. He used precious metals, but he took equal delight in plastic laminates. He created new hues for Corian, DuPont’s acrylic/mineral countertop.

Sottsass also sought to imbue architecture with emotion and delight. He designed the Mayer-Schwarz Gallery on Rodeo Drive in Beverly Hills, with its dramatic doorway made of irregular folds and jagged angles, and the home of David M. Kelley, designer of Apple’s first computer mouse, in the Bay Area city of Woodside.

“The house had to have different spaces, different psychological movements: sad, happy, light, dark, to take care of life,” Sottsass said in a 2002 San Francisco Chronicle article.

Sottsass was born Sept. 14, 1917, in Innsbruck, Austria, and grew up in Milan, where his father was an architect.

In 1939 he graduated from Politecnico di Torino with a degree in architecture. He was called to serve in the Italian military and spent much of World War II in a concentration camp in Yugoslavia.

“There was nothing courageous or enjoyable about the ridiculous war I fought in,” Sottsass said in a 2007 article in Cabinetmaker.

After the war, Sottsass married Italian writer Fernanda Pivano (whom he divorced in the 1970s) and opened his own architectural and industrial design studio. He played an important role in the postwar resurgence of Italy.

Beginning with his work as a design consultant to companies such as Olivetti in the late 1950s, Sottsass began breaking away from the rationalist, industrial design that dominated that era.

In 1959 he won Italy’s highest design award for his redesign of the casing for Olivetti’s huge mainframe computer. Sottsass lowered the height of the machine so workers could see one another. By adding color blocks, he distinguished various components of the computer from one another.

For Valentine, the portable typewriter with a lightweight plastic casing that he designed with Perry King, he chose red, the color of the Communist flag, of blood and of passion. Compared with the typical drab typewriters of the day, the 1969 Valentine was more pop art than industrial machine -- and the public loved it.

In the early 1980s, Sottsass and a group of friends, all in their 30s except for Sottsass, came together to form the Memphis Group. They were sitting around drinking and listening to Bob Dylan, whose “Stuck Inside of Mobile With the Memphis Blues Again” gave them the name of the group.

The designers created furniture and other objects with flair; they used bright colors, slick surfaces, odd shapes and sizes. “We are trying to show that there are other ways of doing things,” Sottsass said in a 1985 Washington Post article.

Buyers included fashion designer Karl Lagerfeld, who is said to have walked into a Memphis opening and said, “I’ll take one of everything.”

“Memphis is like a very strong drug. You cannot take too much,” Sottsass said in a 1986 Chicago Tribune article. “I don’t think anyone should put only Memphis around: It’s like eating only cake.”

In Italy and much of Europe, Sottsass’ contributions are well-known.

“It was Sottsass and a few others, notably Achille Castiglioni, who showed how contemporary design could go beyond the utilitarian, or the cynically manipulative, and become a genuine form of cultural expression,” Deyan Sudjic, director of London’s Design Museum, wrote in Design Week. Last year, the museum mounted an exhibition of Sottsass’ work.

Max Palevsky, the philanthropist and friend of Sottsass who funded the LACMA exhibition, met resistance when he first took the idea to other museums in the U.S.

Yet Sottsass’ influence is far-reaching. He never retired and was determined, it seemed, to continue producing work that “reflects the moment when you are still surprised by life.”

“For me, as an Italian, I think that life is a commedia; it’s not a mathematical drawing,” he once said.

Information on survivors was incomplete.

--

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.