Artworks that cut deeply

- Share via

OFF to the side, near the floorboards, rests a freshly cut silhouette. Not yet entirely separated from the whole, this single sheet of paper looks innocent enough: flat black paper, a trail of flowing, eloquent blade cuts sweeping through it.

It lies in wait, soon to be set in place, affixed to a gallery wall amid the ordered chaos of preparation -- crates being unpacked, lighting tested, wall text configured and a boom box booming -- just two days from the opening of artist Kara Walker’s career retrospective at the Hammer Museum: “My Complement, My Enemy, My Oppressor, My Love.”

Just beyond the crates, the thrum of the staff at work, a couple of dozen more of Walker’s intricate cutouts animate the expanse of a bright white wall. They’re delicate, graceful, even elegantly old-timey at first glance. Then something shifts abruptly. Reading the tableau left to right: A Southern belle in a hoop shirt and her beau romance beneath a moss-draped tree, but close by something else is at work -- a slave boy has wrung the neck of a fowl, a slave girl with pickaninny plaits lifts one leg, dropping babies as if she is defecating them, a young slave boy fellates what might be the master’s son, and so on.

As the story broadens, or rather, disintegrates, the world isn’t what it at first seems. Those silhouettes -- a suspended parade of violence, raw sexual fantasy and a cakewalk of antique black stereotypes -- seem to float in time and in space between phantasm and nightmare.

This is the slipstream that is Kara Walker territory: Walker, the woman who wields the blade.

A polarizing figure

This piece, “Gone, An Historical Romance of a Civil War as It Occurred Between the Dusky Thighs of One Young Negress and Her Heart,” spread out across a 52-foot wall, in many ways the exhibition’s centerpiece, has served as both breakthrough and lightning rod for Walker, whose career has walked paths both storybook and nightmare. At a moment when she was being lauded (a MacArthur Fellow -- the youngest -- at 27), she was being vilified for dealing in stereotypes in an opportunistic way, playing to the white art-world establishment. (Artist Betye Saar called for a boycott, calling the work’s content “revolting,” a betrayal of African Americans.)

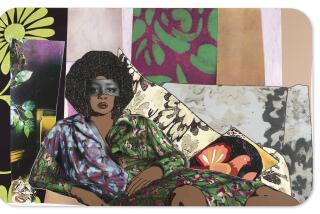

It might seem that age 38 is far too soon to take a long, thoughtful look back on a career. But Walker and her expansive trajectory seem ready for deeper assessment. Her work gazes unwincingly at the reverberations of oppression, violence, sexual abuse, hatred, stereotypes, racism. Much of it revisits the ragged scar of American slavery through silhouettes, puppetry, film, cycloramas, watercolors, colored projections, paintings, pen and ink, and more recent work including collage, film and video and mixed media. And along the way, Walker’s art has unleashed a gunnysackful of passions, both accolades and criticism.

What has kept the work trenchant, honed its edge keen, says Thelma Golden, director of and chief curator at the Studio Museum in Harlem, “is that it is incredibly honest and incredibly direct. There is a lot of work that is about a distancing [from the pain of slavery], about distancing a viewer’s reaction. But Kara speaks to it directly. You feel her very directly in the work. And that feeling is what you can’t turn away from. You both want to walk in deeper and walk away.”

The response to the work has left Walker in the space between, a space she had become somewhat accustomed to over time -- the territory between dark and light, interior and exterior, oppressed and oppressor and here and not there; power and powerlessness. “I’m interested in those moments,” says Walker, “when the subject and their peccadilloes overwhelm any kind of intellectual arguement.”

Walker, who lives in New York, is hoping for a little piece of Southern California sun, so she finds a place outdoors to converse, away from the echoes of the workers, away from the echoes of the work itself. She is tall and swan-like, with a long, graceful neck and gentle, probing eyes. She seems to float rather than walk, taking long, languorous strides, and too, there is something that feels innocent about her -- but a sharp flash of wit and conspiratorial laugh signal something else, something more: That things are not what they seem.

Of late, Walker has been in reflection mode, back in the spotlight as this exhibition, which originated at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis (organized by Philippe Vergne), has made its rounds to the ARC/Musee d’Art moderne de la Ville in Paris and New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art. The Hammer is the final stop.

This show reunites Walker with the museum’s director, Anne Philbin, who first gave Walker her breakthrough New York show at the Drawing Center in 1994 and suggested that she affix the cutouts to the wall. “She showed up with an X-acto knife, a roll of black paper and some glue,” Philbin recalls, “and then disappeared into the basement to make this staggering piece -- ‘Gone.’ She was all of 24. It was as if she was born a full-blown artist. The work was fresh. Mature.”

Though this is one of the few interviews she’s agreed to along the way, she’s been present, giving talks and participating in a handful of public events and is ready for whatever else -- conviviality or controversy -- lies ahead. “You know . . . I just walk down the street with banners with my name on it. I’m no longer ‘little me,’ ” she says, then lets float a quiet smile.

Her work grew out of explorations, physical and interior, of swampy, murky territories -- the incongruities and dualities, the unlikeliest of intersections, territories both real and imagined, both feared and longed-for. While the pieces take on the relationship between master and slave, oppressed and oppressor, they also point to how stereotypes and cliches continue to manipulate our consciousness and shape the notion of our selves.

Old issues live on

The South isn’t dead in her work, because the South and its story are still alive in her imagination. Unhealed is the wound of slavery and unresolved the nightmare of racism in her world or in ours. Walker’s work pulls away the facade of the master’s house, literally and figuratively, the behind-closed-doors bedlam and abuses, and in doing so she is mining those shadows.

“She’s taken what’s thought of as old-fashioned, 19th century ladies work and made it so fresh and so astonishing,” says Gary Garrels, the Hammer’s senior curator, who became aware of Walker at the Drawing Center show. “There is such elegance and beauty, but all of a sudden, it’s a nightmare that kind of creeps up on you. And once it catches you, it becomes difficult to disentangle.”

Born in Stockton, Walker relocated to Atlanta with her family at 13, when her father, a painter and college professor, accepted a job there. She began to have dreams “like a vague sort of stereotype-of-the-South dreams, like I had Klansmen nightmares,” she says. “And it makes me laugh now because the nightmares I should have been having should have been about the Atlanta child murders, which were current,” says Walker. “The thought: There’s a killer on the loose, and he’s after black children, and I’m one.”

Past often trumped present there. Juxtaposed against her early years in California, Atlanta was like a theme park with its Civil War memorials and “Gone With the Wind” parties, and yes, even a Klansmen rally. But the rally, instead of being a nightmare, says Walker, “it was sort of perfect. I didn’t get hung. Nothing bad happened. It was just a reminder of like putting black people -- or white supremacy -- in its place. Like a resurrection of these kinds of, what I thought might be ancient values. It was kind of like stumbling through teenage years and always running across something where history slaps you in the face.”

There too was a strange social stratum to piece together: Back in Stockton, she had begun to understand herself in relation to mixtures -- “All my friends were Chinese. Nobody wanted to be white. I didn’t know any white people.” But in Atlanta, she says, “I felt like a Martian. There were black people and there were white people.” So she just clung to the middle space. “You have to keep in mind that my getting bearings means kind of like . . . well, I was kind of like inward and sort of spent a lot of time fantasizing and dreaming things up. And you know, trying to figure out what people were talking about, without really asking questions,” says Walker, “because that would get me in trouble.”

So she kept to herself: reading, collecting images, drawing -- dreaming herself into being. Walker tried her best to feel her way through this space, “tripping through adulthood, maturing sexuality, where all of these things are compounded, yet again.” She was picking up clues everywhere -- the romance novels women would buy by the gross at her part-time bookstore job (“I thought: Well, there’s something [here] not being met in real life”), erotic art. “I was also interested in the way that objects accrue and then lose history or meaning, in how those objects, or icons, reassert their presence or their strengths,” she says.

The work of that period makes her cringe: “What does it matter?” she says dismissively. But there were the roots of something, she says: “Naked bodies flying through the air.”

Being a black girl

For quite some time, Walker didn’t make art that was overtly about blackness. Not as an undergraduate at the Atlanta College of Art, where she was criticized in class for that choice, and not, at first, at the Rhode Island School of Design, where she began working on an MFA. But there, freed from Atlanta and its hovering ghosts, “I was feeling embroiled.” She’d begun to think more about the effects of the echoes of history, of sexuality, of race, of simultaneously being seen and not being seen. Why did stereotypes still possess so much power? And she decided to confront what was at the center of all this swirl for her, the thing she had been deflecting: “What was this thing about being a black girl?”

Something going on in her periphery caught her full attention, the alleged rape, later revealed as a hoax, of a young black woman, Tawana Brawley, based in Wappingers Falls, N.Y.

“That event sort of pushed a silent button,” she says. “The moment that it was revealed that nothing happened, that there was this fantasy concocted that was so viable . . . I felt it made a victim out of all black women.

“Maybe this is very impersonal of me, but what was it to be in a place, like in the romance novels, where you actually feel like you have this bodice-ripping, provocative figure to sort of justify your being here? Your womanhood, your sexuality or your victimhood -- or all of it? The messy jumble of it.”

It was like a gantlet thrown down. “If my work wasn’t black enough, well, then I’ll make it so black! I’m not dodging it anymore.”

The image that emerged was a large piece -- not a painting this time, but a silhouette. “I’d [been] looking at . . . these silhouette cutouts when I realized that they were cutouts of white people,” she says. “There was a sort of funny reference to minstrelsy, and was there some sort of desire to be black? What is the desire for the shadow? Is it the dark side of the psyche? It was almost like one of these rolling thoughts that kept growing. Everything kept coming back to the silhouette . . . this idea about this blank space; this idea of sort of being present but removing my presence sort of thing. That’s when I realized I had to take the black paper and take the image away from it.”

The first piece wasn’t dodging anything: “A white guy [having sex with] a pregnant Aunt Jemima figure in a kerchief and him shushing her. And it’s all sort of ecstatic. It was too involved for the paper to stay upright. But it did get a pretty good reaction -- “ she pauses: “Silence.”

Precautionary measures

Silence. Fury. Unease. Awe. Confusion. Her own fury ignited fury. This work that had come out of Walker’s own simmering disquiet still taps into something so painful and unresolved that you can’t not have a reaction. With that in mind, the Hammer is prepared if, or when, someone takes umbrage. Senior staff, says Garrels, is being trained, and handouts explaining the artist’s intentions and the works’ context will be distributed.

But, says Golden of Harlem’s Studio Museum, Walker has “been stronger than the words put to her. She knows who she is and is fierce about it. I don’t know if the response to the work has died down. But there has been acknowledgment of the work’s power. Now the conversation has turned: It is about the work, not about the controversy.”

People do still react, says Walker, “but it doesn’t feel as ‘furious.’ I think the culture has changed; some of the raw quality of the work has leeched out,” she says. Another smile drifts across her face, yet just as quickly her expression shifts, sobers.

“But there’s this other weird thing, you know. People come who never have been to an art gallery, but they’ll come to my show because they saw an article and they are just pleased to see that there’s a woman -- a sister -- making it. And I don’t quite know what to do with that,” she says. “Would it be better to go back to the ‘I hate it!’ ‘You’re controversial!’? You know? Maybe this isn’t the stuff to be ‘celebrating.’ This isn’t about celebration. Something bad happens to all of these people.”

--

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.