Fans fight to keep their field Wrigley

- Share via

CHICAGO — Over the last eight years, baseball fans have watched Pacific Bell Park in San Francisco become SBC Park -- and now cheer on home runs from the seats in AT&T; Park. Fans in Houston tried to have a sense of humor when Enron Field became Minute Maid Park -- by nicknaming it the Juice Box.

But many Chicago Cubs fans vow they won’t accept a new name for their beloved Wrigley Field.

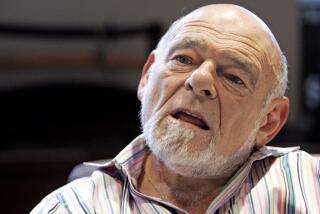

When an $8.2-billion privatization deal gave local real estate magnate Sam Zell control over Tribune Co. -- as well as the Cubs and the second-oldest ballpark in the major leagues -- in December, the new owner said he planned to sell both the team and the field.

But the emotional firestorm now roiling residents and Cubs fans is the result of Zell’s comments on CNBC last month that he was considering selling the naming rights to the 94-year-old ballpark.

Local talk radio listeners have burned up the airwaves, while sports blogs have been flooded with screeds against Zell. The Chicago Tribune newspaper’s rival, the Chicago Sun-Times, launched a contest over the issue: It has offered $1,000 to the person who writes the best song about the potential name sale and turns it into a YouTube video.

For these outraged fans, the ballpark is an enshrined piece of the city’s soul, and the bustling North Side neighborhood surrounding it -- and named after it -- a haven to Chicago’s past. And in a town where the baseball team you cheer for says much about your economic status and neighborhood loyalties, heaven help anyone who dares to change that shrine.

“Congratulations on becoming the most despised man in Chicago,” wrote one of the outraged on a Sun-Times online forum. “You have quite the legacy to look forward to.”

This is a town that cherishes its traditions. Residents here still mourn the passing of the Marshall Field’s brand. Protesters occasionally gather in front of the department store’s former downtown jewel, now a Macy’s.

Zell, whose Tribune Co. owns the Los Angeles Times, declined to comment for this article. When asked by CNBC about the outcry, he replied: “Excuse me for being sarcastic, but the idea of a debate occurring over what I should do with my asset leaves me somewhat questioning the integrity of the debate. I think there’s a lot of people who would like to buy the Cubs and would like to buy the Cubs under their terms and conditions and, unfortunately, they have to deal with me.”

Zell later said, “Perhaps the Wrigley Co. will decide that, after getting it for free for so long, that it’s time to pay for it.”

(On Wednesday, Wrigley Co. Executive Chairman Bill Wrigley Jr. told shareholders that he and his family shared a “great passion” for the team and baseball, but the company hadn’t decided whether it would make a bid to control the park’s name.)

The debate reignited in recent days after Crane Kenney, the Tribune Co. executive in charge of the Cubs, said that three corporations were interested in the naming rights, though no deal was pending. He also told reporters last week that the famous red-and-white Wrigley Field marquee might be able to be altered, regardless of the park’s status as a city-designated landmark.

Saying the structure of the marquee itself is landmarked, Kenney told the Chicago Tribune: “We believe the 1st Amendment protects what letters we write on the marquee. . . . [T]hroughout the ballpark, we’ve always maintained that with the city, with our advertising, nobody can tell us what our advertising can say or won’t say.”

A Cubs spokeswoman said Wednesday that Kenney stood by his earlier statements and had no more to add.

The news comes at a key time for Cubs fans, arguably among the country’s most superstitious. With less than three weeks until the season opener, this year marks the 100th anniversary of the last time the Cubs won a World Series, believed to be the longest streak of futility in major American professional sports.

The ballpark, built on the grounds of a Lutheran seminary, was dubbed Wrigley Field in 1926 in honor of the team’s then-owner, William Wrigley Jr. That Wrigley happened to also be the name of the chewing-gum company he founded was more happy coincidence than a savvy corporate marketing move, said Ed Hartig, a historian who specializes in baseball research.

“For many years, they didn’t even sell Wrigley gum in the ballpark,” Hartig said. “It didn’t have the company logo out front.”

But these days, the naming rights of baseball fields is big business: The New York Mets have finalized a 20-year, $400-million deal to name their new ballpark Citi Field, after years of playing at Shea Stadium.

Some Cubs fans see a ray of hope: The Illinois Sports Facilities Authority, the state agency that owns and runs U.S. Cellular Field, the South Side stadium where the Chicago White Sox play, said it expected to make an offer to buy Wrigley Field this month -- which, if completed, may help move along plans for multimillion-dollar renovations to the park.

Still, such hope is wrestling with fans’ anger and, for some, resignation.

Each year, Kurtis Evans and his girlfriend, Carolyn, make a ballpark pilgrimage from their home in Toronto. They wander along Wrigleyville’s tree-lined streets, where signs in the row-house windows warn pedestrians to watch out for foul balls.

“As far as I’m concerned, they can call it the ‘Budweiser Presents the Sears Center at Wrigley Field, on the Best Buy grounds in Chicago,’ as long as the money goes into the players and maintenance of the ballpark,” said Evans, 28, who co-founded the fan blog Goatriders of the Apocalypse. “In the end, we’ll still call it Wrigley.”

--

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.