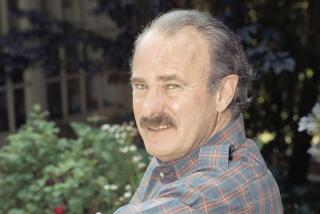

Ohio State’s Kurt Coleman is a true leader

- Share via

The phone call came three years ago this month. Kurt Coleman remembers it as if it happened yesterday.

It’s hard to forget the night your father called to tell you he was dying.

“It was Dec. 3, 2006,” said Coleman, Ohio State’s All-Big Ten strong safety. “And he basically just said ‘I have cancer.’ I started laughing. Why are you joking?

“And he was like, ‘No, I’m serious.’ ”

It was breast cancer, a disease so rare among males it strikes fewer than 2,000 American men a year. But it kills more than 20% of those it attacks.

In the time it took for the laughter to turn to tears, football took on a new role for Coleman, then an Ohio State freshman. If millions of people were willing to hang on his every word just because he could run fast and jump high, he figured he might as well take advantage of it.

So Coleman, now an Ohio State team captain, started a campus group to raise money and awareness for the fight against little-known diseases such as male breast cancer, kidney cancer and Charcot-Marie-Tooth (CMT), a debilitating neuromuscular disorder similar to muscular dystrophy.

The results have far exceeded anything the eighth-ranked Buckeyes have accomplished on the field this season.

“I can’t speak higher of Kurt,” said David M. Hall, chief executive of the Charcot-Marie-Tooth Assn., a national nonprofit education and awareness group. “For Kurt to, on his own, adopt the cause and reach out to us, brought us a degree and an awareness and a spotlight that, quite frankly, we didn’t have before.

“Kurt created a momentum that helped us in everything we did this year.”

That included pressuring Congress for a recently awarded $1-million allocation to help diagnose and treat the disease.

“I can’t tell you what it says about these guys,” Hall said. “Kurt Coleman, in my opinion, will be running for office one day. He’s a leader.”

Ohio State Coach Jim Tressel agrees, and Coleman’s teammates voted him most valuable player.

Tressel says that leadership comes not from Coleman’s team-leading five interceptions or his 64 tackles. Nor from the various honors that, with a win over Oregon in Friday’s Rose Bowl, would make him the most accomplished player on the winningest senior class in school history.

Those qualities, Tressel says, were forged not in on-field success but rather in tragedy, beginning eight months before his father’s cancer was discovered.

“Adversity, in my experience, is probably one of the few things that makes you strong,” Tressel said. “It’s just the kind of person he’s become.”

Coleman’s strength was first tested just weeks after he graduated from high school, on an otherwise ordinary play during spring practice at Ohio State. A walk-on wide receiver named Tyson Gentry ran a simple curl pattern in front of Coleman and as he turned to run upfield, Coleman made the tackle, snapping a vertebra and leaving Gentry paralyzed.

“When I had to go see him for the first time, it was honestly a very hard experience,” remembers Coleman, who was so distraught he nearly quit football. “His family kind of came and hugged me and said everything was all right. And then [Gentry] came and told me everything was OK. Ever since then, our friendship, it’s been getting closer and closer.”

Coleman needed friends that winter when his father received his diagnosis of cancer.

“It’s a life-changer for you, the whole family,” said Coleman, who found himself drawn first to the Bible, then to hospitals, where he would visit the sick or work with disabled children.

With former teammate Matt Daniels, whose father had kidney cancer, Coleman founded a campus chapter of Uplifting Athletes, a nonprofit organization established to help those with rare diseases.

“I’ve always felt like I’ve been a person that’s been mature for my age. And going through that I had to lean on God,” Coleman said. “But I think [those events] kind of built me to who I am and I think they made my family a lot stronger.”

Coleman says his father, Ron, a high school assistant principal in Ohio, “is 100% cured” and has embarked on his own educational crusade about male breast cancer.

Gentry, who has regained some motion in his extremities, may walk again someday. “He’s still got a long way to go, but he’s made so much progress,” Coleman said.

So has Coleman, who has turned the two tragedies into something positive.

“He knows when he was going through tough times there were people there for him,” Tressel said. “He has the podium, per se, to be able to help out his teammates.”

He used the platform he had as a star athlete last summer when he staged a well-attended benefit to combat CMT, the inherited neurological disorder that plagues the father and aunt of Ohio State quarterback Terrelle Pryor.

“What Kurt did, that’s cool,” Pryor said. “He went out of his way and picked that because it was my father’s illness.”

For Coleman, who knows what it’s like to have a sick parent, it’s a way to give back.

“We’re blessed with so many things, people in our position,” Coleman said. “It doesn’t take a lot of time, it doesn’t take a lot of energy. It just takes a lot of heart.

“And I feel like if more people could do it, this world could be a lot better. I’m just fortunate enough to be in a position where I can make a difference in someone’s life.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.