Why death doesn’t end the debate on Updike

- Share via

In an often-overlooked 1992 novel with perhaps the most intentionally dull title in literary history -- “Memories of the Ford Administration” -- John Updike has fun with an issue that long deviled his career. He introduces a character named Brent Mueller, a “rapid-speaking fellow with the clammy white skin of the library bound” who had “deconstructed Chaucer right down to the ground.”

Mueller serves as antagonist to the novel’s narrator -- both are professors at a New Hampshire college -- and becomes a campus cult figure by deeming every masterpiece “a relic of centuries of white male oppression, to be touched as gingerly as radioactive garbage.” The protagonist, in return, cuckolds the deconstructionist throughout the book.

This was the author’s way of playfully pushing back at his critics and detractors.

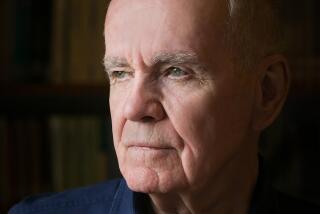

Updike’s death last month was met with the usual fulsome praise and sighs of sadness. But the writer, who was regarded as a gracious, decent man, was not unanimously loved or respected in the literary world. Over the years, he had become a symbol of the out-of-touch, tweed-wearing realist to younger, more experimental writers, a lightning rod for arguments over what contemporary fiction should be.

Updike was attacked by both figures from the cultural right (Norman Podhoretz, Tom Wolfe) and left (Sven Birkerts, Cynthia Ozick). Harold Bloom damned him as “a minor novelist with a major style,” while James Wood, possibly the most influential critic of his generation, slashed the “provincial” and “complacent” Updike every chance he got.

“This astonishingly gifted and creatively vital writer, who started to ‘win’ at the age of 22 when the New Yorker bought a story and a poem that he had submitted,” wrote Lee Siegel on the Daily Beast, “this literary genius had, by the end of his career, become either a target of ridicule or been forgotten by literary culture altogether.”

For many, Updike was perhaps the most famous American writer. His quartet of novels about Harry “Rabbit” Angstrom are on a very short list of postwar books that rank in the antique category of the Great American Novel.

He was widely admired for his stories, many of which chronicled what he called “the American Protestant small-town middle class,” as well as his literary and art criticism and his sheer output.

“Maybe we’re all jealous of him because he was so prolific,” offered Mona Simpson, a novelist and UCLA English professor and an admirer of Updike’s Maples stories. Indeed, even in death, he continues to publish: “Endpoint and Other Poems” comes out in April, and “My Father’s Tears and Other Stories” will appear in June.

Few challenge the beauty of Updike’s writing. But this has led to one of the main charges: that his was a style without substance. David Lipsky, writing in “The Salon.com Reader’s Guide to Contemporary Authors,” judged that Updike, despite being “the most successful literary writer of his era,” induced discomfort and impatience: “He’s probably still the best word-by-word, thought-by-thought, sentence-by-sentence writer we have, but isn’t it time he moved on?”

Others considered his subject matter too lightweight. Unlike novelists who tackled conspiracy, assassination, drugs, politics, mass murder, war and the whirl of pop culture, Updike aimed “to give the mundane its beautiful due.”

Two writers dedicated to extreme and public subjects were among his harshest critics. Norman Mailer called Updike “the kind of author appreciated by readers who knew nothing about writing.” Don DeLillo, author of sweeping works such as “Libra” and “Underworld,” said he wrote novels that took place “around the house and in the yard.”

“There’s this false narrative,” said Samuel Cohen, assistant professor of contemporary literature at the University of Missouri, “that the history of 20th century American literature is about moving further and further from realism.” The bias goes back, Cohen said, at least as far as Frank Norris, exponent of a rugged naturalism, who dismissed the realist writing of his day as the drama of broken teacups.

By the late 1960s and 1970s, Cohen said, realism is “seen as aesthetically reactionary. If you’re not a fabulist or a postmodernist, you’re writing in an old-fashioned, boring way.”

Perhaps the most famous attack came from David Foster Wallace. In a now-notorious 1997 essay for the New York Observer, he tarred Updike, Mailer and Philip Roth as the Great Male Narcissists, or GMNs. “Most of the literary readers I know personally are under 40,” he wrote, “and a fair number are female, and none of them are big admirers of the postwar GMNs. But it’s John Updike in particular that a lot of them seem to hate. And not merely his books for some reason -- mention the poor man himself and you have to jump back.”

Wallace was getting at a generational shift that had to do with more than literature. “I’m guessing that for the young educated adults of the ‘60s and ‘70s,” he wrote, “for whom the ultimate horror was the hypocritical conformity and repression of their own parents’ generation, Mr. Updike’s evocation of the libidinous self appeared redemptive and even heroic. But the young educated adults of the ‘90’s -- who were, of course, the children of the same impassioned infidelities and divorces Mr. Updike wrote about so beautifully -- got to watch all this brave new individualism and self-expression and sexual freedom deteriorate into the joyless and anomic self-indulgence of the Me Generation.”

Not all writers born in the 1960s felt the same way. “I’m roughly the same age as the writers who were complaining,” said Bret Easton Ellis, “but I learned so much from those older writers. Was it just time for the Angry Young Men to clear the mantel?”

Maybe Updike, who was devoted to “middles” of all kinds, occupied the central place in American letters for so long that he became an obligatory figure to revolt against.

Throughout his career, he played the role of a consistently retro figure -- his first published work was light verse. He played golf, non-ironically.

Although he grew up a teacher’s son in small-town Pennsylvania, his literary background was Harvard and the New Yorker; his publisher was Alfred A. Knopf. The fact that he’d supported the Vietnam War just filled in the caricature.

A writer’s reputation is shaped as fully after death as when he or she is alive. Publications, scholarship and other factors keep a writer in the canon, or not. In academia, Updike’s stock is a few notches higher than Ayn Rand’s.

“He does not get written about as often as you would think,” said Cohen. Updike, Cohen continued, doesn’t appear in dissertations as often as DeLillo, Toni Morrison or Thomas Pynchon. And he doesn’t show up as often in conversation with students as Raymond Carver, who in addition to being a powerful writer had the mystique of being a self-destructive alcoholic.

“Writers go in and out of fashion,” said Simpson. “I don’t know that my students are reading James Joyce right now. They may not be reading Updike, but they may be in 20 years. He’s not a writer like Carver who’s had legion of influences -- he’s a more transparent writer, so he can’t be as easily imitated.”

It may be that while some writers transcend their time and place, Updike’s best quality was his ability to chronicle them accurately and in detail.

“There’s not going to be another writer charting what’s going on in his generation in the same way,” said Ellis. “Who gets on the cover of Time the way he did, and became a national debate: ‘What does John Updike mean?’ ”

Lipsky called Updike the literary world’s “class president”; that world may never again support such an office. In a world without a center, he seems from another age.

Will there ever be another figure so many can disagree about?

“It’s another nail in the coffin,” said Ellis, “of a kind of American literary culture. Which makes those four Rabbit books even more important -- that is the main text people will go back to.”

--

Timberg blogs at scott-timberg.blogspot.com.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.