War’s true cost -- my friend Ben

- Share via

I thought I knew the cost of combat. I recommended plans to spend billions of dollars in Afghanistan from my desk at the White House Office of Management and Budget. But it was not until last month, as I stood on the tarmac at Tweed-New Haven Regional Airport in Connecticut watching my friend’s flag-draped coffin come home, that I truly understood the price of war.

Army Capt. Ben Sklaver, 32, was killed in a suicide attack in what was the deadliest month for U.S. soldiers since the war in Afghanistan began in 2001. At the time, he was trying to meet with local leaders in a village outside Kandahar to see what infrastructure they needed. To those at home who see our troops strictly as combatants, this is not a traditional soldier’s role. But Afghanistan is a new type of war, and Ben was on the front line.

Ben was in a civil affairs unit, tasked with showing tangible progress to counter the Taliban’s effort of intimidation. The work appealed to him. Bringing people basic infrastructure such as water and schools fosters hope in a region desperately lacking it. Ben was eternally optimistic, and despite numerous close calls, he proudly told me a week before his death that he was making progress.

Such optimism and sense of purpose had previously led him to start a nonprofit organization, ClearWater Initiative, focused on bringing fresh water to conflict-ridden regions in Uganda after his first tour with the military there in 2007. Villagers whom his organization helped thanked Ben for his “miracle” of water.

Ben’s death robs not only his fiancee of a husband and his family of a son, it denies the world his unrealized potential, including the “miracles” that may have been in Ben’s mind for Afghanistan on his return. This is a price our leaders must consider as they define our new strategy in the region. The cost of war is not just the billions spent on guns and bullets, but a trade-off between losing the future of soldiers like Ben for the hope that a greater good is achieved.

For too long, that full accounting of war was hidden from our national emotional balance sheet. The media were prevented from showing the return of the dead; even families of the deceased were unable to make the trip to Dover Air Force Base to view their loved one’s arrival.

Watching my former roommate unloaded from a plane in a silver container brought an indescribable pain. But for family members and those close to the soldier, watching the arrival is an important step in coming to terms with the loss. The ritual, the simplicity, the slow process of salutes and patriotic symbolism offer an important modicum of comfort for what is one of the worst experiences life can provide. It brings home the reality of death, both physically and emotionally.

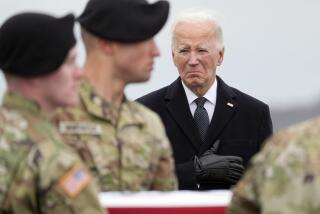

President Obama’s decisions to allow media coverage of returning coffins, to assist families of fallen soldiers to come to Dover and to attend a ceremony himself last month are significant steps for us as a country to fully account for war. They highlight the total price of war -- not just the more than $200 billion spent so far but also the thousands of lost futures both here and in Afghanistan.

What’s most disheartening this Veterans Day is that many of us, including some in government, are still too far removed to truly appreciate that our troops are engaged in battle daily. Maybe it is because the money we spend is too large, the costs too abstract or the fighting too far away from our daily lives to comprehend. I have no doubt that sentiment was true for many in southern Connecticut. That is, until Ben came home.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.