Blake Edwards: an appreciation

- Share via

Every one of us working in film comedy today is a descendant of Blake Edwards. Some of us more than others, to be sure, but one way or another, in ways both overt and subliminal, Edwards’ films have influenced film comedy ever since.

I remember watching his “Pink Panther” films as a kid and reveling in the pure, unabashed silliness of Inspector Clouseau’s high jinks. As I grew into adulthood and a career in film comedy, I revisited Edwards’ films and was struck not only by the enjoyable-as-ever zaniness but also with a newfound appreciation of the more nuanced elements at work.

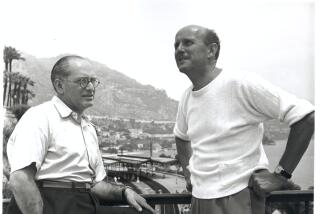

Edwards’ most famous collaboration was, of course, with the brilliant Peter Sellers. Together, Edwards and Sellers crafted a character whose hilarity across several films remains one of the landmark icons of cinematic comedy.

Edwards somehow managed to imbue in Clouseau a blend of arrogance and pathos, obliviousness and savvy. Edwards’ “Pink Panther” films were deceptively complex in their construction. Like all great comedy, they employ a variety of kinds of humor, seamlessly blending both verbal and physical comedy, the latter of which in particular remains among the high-water marks in film history.

Edwards had a nose for frame size, using tighter close-ups when a verbal joke required a more focused payoff, while lying back in wider, head-to-toe frames and longer editorial pieces needed for physical comedy. Edwards’ mise-en-scène was unobtrusive and fluid, often using the blocking and movement of actors to keep refreshing and reconstituting the composition within the frame. Edwards embraced and exploited the wide shot in ways still emulated by many of us making comedies now. He gave his actors — and his one central star in particular — room to breathe, room to perform. He recognized that for certain performers, of which Sellers was surely one, the entire body was required to convey a performer’s mojo.

(I learned this lesson the hard way, once shooting Ben Stiller in a medium close-up, cut at the chest, only to watch dailies and realize that Stiller’s gesticulations were a critical part of his comedic performance. I rarely framed his hands out in comedy scenes again.)

Which brings me to what may be one of the most instructive aspects of Edwards’ oeuvre: his collaborative relationship with his actors. Edwards recognized that directing comedy was in large measure the construction of a scene, a sequence, a film, that was tailored to the specific talents of one’s star. In the “Pink Panther” films, we can bear witness to one of the greatest-ever such collaborations. Throughout shoots that were hardly without difficulty or friction, Edwards recognized the ineffable elements that made Sellers brilliant, and his films with Sellers (both the “Pink Panther” series as well as “The Party)” betray a canny and supremely confident orchestration of those talents.

These are just a few of the instructive gifts that Edwards’ films gave those of us who work in film comedy. Of even greater value, however, are the films themselves and their place in our collective cultural memory. From “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” through the Clouseau films, “10” and “Victor, Victoria” (to name but a few), Blake Edwards’ movies gave us characters to remember and laughs that sneaked up on you and laid you out cold. Edwards himself compared his comedy to “blindsiding” the audience, saying: “A quarterback will be looking to throw a pass downfield when all of a sudden, he’ll get nailed by a tackler he hasn’t seen. Suddenly, he’s wiped out, and I think that’s my job — to sort of blindside people in order to shake them up.”

Well, Mr. Edwards, you certainly did that: shook us up and laid us out, leaving us with laughs and cinematic memories that will endure long, long after the lights come up.

Director Levy’s credits include “Night at the Museum,” “Date Night,” the remake of Edwards’ “The Pink Panther” and next year’s “Real Steel.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.