A Nobel’s long gestation

- Share via

There’s a good chance that you know, or know someone who knows, one of the more than 4 million couples worldwide who have had a child through in-vitro fertilization. The procedure isn’t considered a big deal these days, just another option for people who have had trouble conceiving.

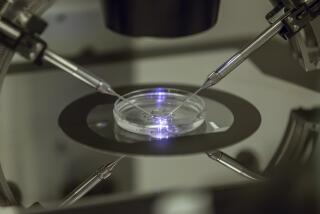

In fact, it’s hard to imagine the amazement, and in some quarters dismay, that greeted the 1978 birth of Louise Brown, the first test-tube (more accurately, petri-dish) baby, who recently celebrated the birth of her own child. Infertile couples suddenly saw new hope. The Roman Catholic Church and other religious groups criticized the new procedure as radical interference in God’s design for procreation. Bioethicists wondered where it all would lead. If we could create human life outside the womb, they asked, what sort of new procedures might be developed as science leaped ahead of societal consensus on the issue?

Seldom has a recent Nobel Prize winner in physiology or medicine more directly affected the lives of millions than Robert G. Edwards, the British biologist who was named as the 2010 recipient this week. And seldom has a winner confronted so many societal hurdles. The British government refused to provide funding for the work, so Edwards and his late colleague, Patrick Steptoe, obtained private grants. Many observers suspect that religious and other opposition kept the pair from winning the prize long ago.

Today, most of the criticism has faded away, and although the Vatican still formally objects to in-vitro fertilization, it says little about the subject. Yet the bioethicists had it right; in-vitro fertilization not only allowed the births of millions of babies but opened a whole new chapter of debate about what constitutes a human life.

As happy as society is for the families created through in-vitro fertilization, we’re back to the original discussion when it comes to supporting other, even greater breakthroughs the procedure might make possible: the discovery of new cures for serious illnesses through embryonic stem-cell research. Again, a national government — our own — refused to provide the needed funding under the George W. Bush administration. Proposed loosening of restraints by the Obama administration is being fought in court. Discussions of the moral limits of science help to guide the rules for progress, but they should not be allowed to hold back ethically conducted research in this promising field. If those dreamed-of cures become reality in a few decades, there will be new celebrations, new prizes won and distant wonder that anyone could have objected to such a contribution to humanity.