On view: ‘China Modern: Designing Popular Culture 1910-1970’

- Share via

Sometimes, a litchi box is more than a litchi box. In a designer’s hands, it can become a work of art, a cultural artifact or a piece of propaganda.

“Graphic design can be put to a number of services and uses,” says Bridget Bray, assistant curator at the Pacific Asia Museum in Pasadena, where a new exhibition explores “the ways such artistry and relativity were in full effect in 20th century China.”

“China Modern: Designing Popular Culture 1910-1970” features more than 160 posters, porcelain figures and everyday objects produced, says Bray, as the country moved from imperial dynastic rule to Western-influenced capitalism to Communism under Mao Tse-tung. “There are limited times in history when such a large populace undergoes such a sea change in such a compressed period. The takeaway for our visitors is understanding how dynamic China is and how that shift from capitalism to communism felt day to day as seen in people’s homes and through graphic designers whose goal was to sell something, either products or politics.”

The show, which closes Feb. 6, was inspired by the 2004 book “Made in China” by Reed Darmon with assistance from Kalim Winata. Darmon, an Oregon collector and designer, lent many of the items on display. Winata, a San Francisco artist and independent curator, serves as guest curator.

“China Modern” examines advertising and packaging in Shanghai in the 1920s and ‘30s when foreign styles and lifestyles were promoted with images that blended Western marketing and Chinese aesthetics. One of the best-known examples is the modeng xiaojie (“modern miss”), the bobbed-hair beauty who adorned calendar posters and cosmetics containers.

After the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, the emphasis shifted from merchandise to Communism and Mao — who appeared on seemingly everything, including posters and teapots. Young women now were depicted as revolutionary heroines happily toiling away, often in jobs traditionally held by men.

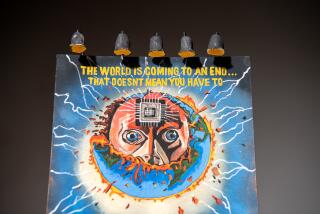

The exhibition ends with a brief look at contemporary takes on retro themes by Asians and non-Asians, including Alan Chan’s multimedia pieces, a Vivienne Tam textile and a Shepard Fairey print. “The Shanghai and Communist era styles were extremely strong,” says Winata. “It’s hard for a Chinese artist today not to have been exposed to these images. Even those not in China have found meaning in them.”

calendar@latimes.com

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.