Voices of Black Los Angeles: He finds comfort in the corporate world

- Share via

This story originally ran in 1982 as part of the “Black L.A.: Looking at Diversity” series. Please note: Our standards on certain terms have changed, but we have preserved the original text in order to provide an accurate account of the work in print.

Tim McChristian’s memory of the civil rights movement is only an image on a black and white television screen, alongside assassinations, war and “Leave it to Beaver.”

Yet McChristian, at age 13, became a direct beneficiary of the civil rights movement when in 1968 he participated in a minority program for high achievers called “A Better Chance.” That program placed him in a prestigious school, Phillips Exeter Academy in Andover, Mass., where McChristian, the son of a metal cutter and a postal worker, mingled daily with sons of the heads of state. Yale University was next, then a master’s degree from USC.

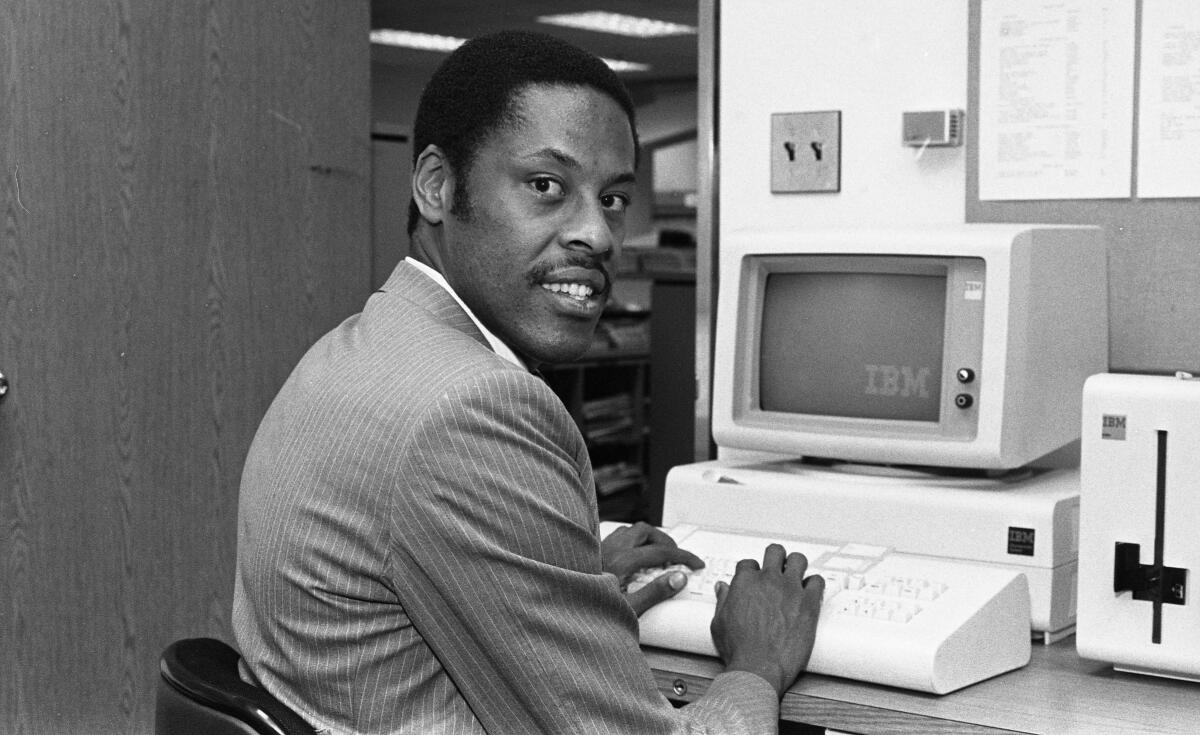

The result—a confident, ambitious dapper single man whose 6-foot, 4-inch frame fits well into tailor made shirts, but who still prefers basketball garb on his days off.

In the summer of 1982, The Times published a series on Southern California’s Black community called “Black L.A.: Looking at Diversity.”

McChristian, 27, is a computer salesman who made approximately $35,000 last year. He talks at length about what is “marketable.” Still, he remains friends with most of the same buddies he knew when he used to play pickup street ball at John Muir Junior High School near USC.

He believes that struggling for economic freedom is a practical alternative to protest marches; his activism takes the form of “networking” with other black professionals who can help each other and the coming generation climb up the economic ladder.

Corporate Environment

McChristian, a black man in a largely white corporate environment, moves between the corporate world and his personal world with seeming ease. He says that is because he understand “you don’t mistake friendship for fellowship or fellowship for friendship.”

But the transition to prep school more than a decade ago was not easy.

“It was total culture shock. I grew up here in L.A., in the community, and the next thing I know I’m in Andover, Mass. But because I was so young I had no biases. Basically you live in a vacuum when you grow up in the city. You hear about the valley and all that but you usually only see it through the back seat of your mother and father’s car.

I’ve provided myself with options. For my children, I would want them to be comfortable. I want them to have options—that’s really the whole key.

— Tim McChristian

“So that was the first time I ever lived with white folks. You know, lived with them. I went from A to Z. It was the first time I’d ever seen snow falling. It just totally tripped me out.

“Now it’s no problem out there dealing in the marketplace. This is the environment I want to be in, doing what I’m doing and being successful. I’m very comfortable in the corporate environment.

‘There’s always going to be a line’

“I have a great time with the fellas at work, we go out and drink. But there’s always going to be a line that very few of them will ever be able to cross. It’s just realistic. Now I’ve been around long enough to know there are cool white dudes just like there are cool brothers. But personally, I share very little in common with those guys, other than, you know, I like to drink beer.

“Just like the Holmes-Cooney fight. One of the guys I work with has a wide-screen TV and he invited all the marketing reps to his house. I said ‘No, that’s all right, I’m going to look at it with some friends.’

“I knew I didn’t want to see that with white folks. I just realized I wouldn’t feel comfortable over there. I also realized the situation potentially of someone getting drunk and saying ‘Beat the nigger up,’ and I would be sitting there in one of those situations you don’t want to be in.

“That’s why basketball is so important to me. It’s something I’ve been able to keep as a link with my buddies. One guy’s a bus driver. One works for the post office. Another buddy has his master’s degree in counseling, and another is a marketing representative. I don’t care. They happen to be my partners and that’s what they happen to do.

“I’ve provided myself with options. For my children, I would want them to be comfortable. I want them to have options—that’s really the whole key.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.