Review: Unrequited love fuels the ‘Fiery Heart’ biography of Charlotte Brontë

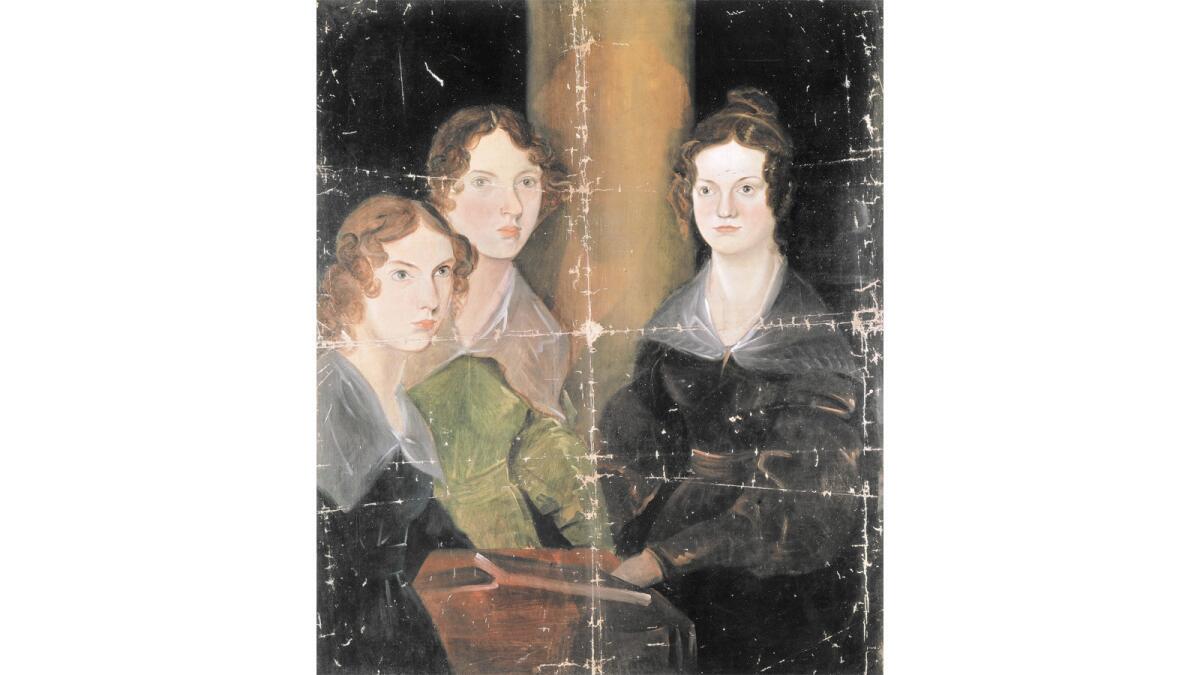

A portrait of Anne Bronte (Thornton, 1820 — Scarborough, 1849), Emily Bronte (Thornton, 1818 — Haworth, 1848) and Charlotte Bronte (Thornton, 1816 — Haworth, 1855), English writers. Oil on canvas by Patrick Branwell Bronte (1817-48), circa 1834.

- Share via

The contours of the Brontë story have been burnished over time into legend: those bleak, wind-swept moors; that isolated West Yorkshire parsonage; the children whose sole playmates were one another; the gender-bending pen names, and finally the Gothic poetry and novels that seemed to prefigure early death.

The longest surviving sibling, best known for “Jane Eyre,” was lionized two years after her 1855 death by friend and fellow novelist Elizabeth Gaskell. Gaskell’s biography, “The Life of Charlotte Brontë.” had the virtue of immediacy but suppressed details of Charlotte’s unrequited love for her married Belgian schoolmaster. Later biographies, including Lyndall Gordon’s “Charlotte Brontë: A Passionate Life” (1994), rectified the omission.

Claire Harman puts the frustrated romance at the center of “Charlotte Brontë: A Fiery Heart,” depicting it as the key to Brontë’s psyche and her work.

The biography begins with a prologue that takes us to Sept. 1, 1843. In vivid, novelistic prose, Harman chronicles a solitary summer vacation at the Pensionnat Heger, a Brussels boarding school where Charlotte Brontë has studied and taught. The “desperately unhappy” 27-year-old is hopelessly in love with her headmistress’ husband, “a man of impressive intellect and spirit” and mercurial moods who would become the template for Jane Eyre’s employer, Mr. Rochester.

After encouraging Charlotte’s talents, Constantin Heger, who has been teaching her French literature, has grown more formal, signaling that he “will never see her in a romantic light.” Ultimately, Harman writes, he will “cost her two years of intense heartache, humiliation and futile hope.”

As she recounts in a letter to her sister Emily and, later, in the novel “Villette,” Charlotte wanders forlornly into a cathedral, an unfamiliar haunt for the daughter of a Church of England minister with Methodist inclinations. There she confesses, in French, to a priest. The experience “solaced” her and “gave her an idea not just of how to survive or override her most powerful feelings, but of how to transmute them into art,” Harman writes.

Publishing this biography to coincide with bicentenary of Charlotte Brontë’s birth in April, Harman assiduously credits previous scholars, especially Margaret Smith, editor of “The Letters of Charlotte Brontë” (1994-2004, in three volumes). Harman mines the latter, which she credits as “the fullest and most suggestive source to date of Charlotte Brontë’s behavior and private opinions,” with considerable subtlety.

Among the extant letters are almost 600 to Charlotte’s school friend, Ellen Nussey, and four heartbreaking epistles to the schoolmaster for whom she pined, Constantin Heger. Harman skillfully interweaves the correspondence with other sources, including autobiographical passages from the novels, to produce as intimate and nuanced account of the writer’s life as we are likely to get.

From the prologue, the narrative flashes back to a depiction of Charlotte’s Irish father, Patrick Brontë. With modest resources but a prodigious work ethic, Brontë attended Cambridge University, published poetry and fiction, married the sensitive, intelligent Maria Branwell and settled at Haworth in West Yorkshire.

His luck turned when his wife died of cancer at 38, leaving five daughters and a son. Her death began a pattern of continual, repeated bereavement — extreme even for the Victorian Age — that would haunt the Brontë family.

Harman is no fan of the widower, a man of “intransigence, pride and emotional blindness.” Not a pure villain nor quite as eccentric as gossip suggested, Patrick Brontë nevertheless aged into a petty tyrant who demanded absolute fealty from his children and almost wrecked Charlotte’s solitary hope of marital happiness.

Tough as life was at Haworth, the Brontë siblings — including the relatively pampered son, Branwell — mostly thrived there, united by their precocious literary and artistic pursuits. They fared less well when sent off, periodically, to boarding school. While away, the eldest sisters, Maria, 11, and Elizabeth, 10, contracted fatal cases of consumption (modern-day tuberculosis), nudging the surviving siblings even closer.

Branwell — creative, well-educated and “holding the trump card of maleness,” as Harman pointedly notes — did the least with his intellectual assets. A failed portraitist, he had an affair with an older married woman, incurred debts and succumbed to alcoholism and opium addiction at age 31.

Despite her academic talents, Charlotte was ill-suited to work as a teacher or governess. But her otherwise disastrous Belgian sojourn inspired her to write her first novel, “The Professor,” “a painfully obvious piece of wish-fulfillment” based on her relationship with Heger. Though rejected repeatedly — it would not be published until after her death — the novel drew respectful notice from her future publisher.

By then, Charlotte and her younger sisters, Emily and Anne, had financed publication of a poetry collection that they attributed to Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell. It would sell, at first, just two copies.

Then came “Jane Eyre,” the novel that in 1847 would (pseudonymously) make Charlotte’s name. Currer Bell’s Jane and Mr. Rochester became lovers for the ages. The book’s “astonishing vividness,” Harman writes, derives largely from an “articulation of long-pent-up-sorrows.”

With its success, Charlotte’s horizons expanded, and she began a second unrequited romance, with her charming, generous and handsome young London publisher, George Smith.

The literary highs were followed by almost unimaginable lows: Branwell’s death in September 1848, then Emily’s in December and Anne’s five months later, both of consumption.

(Emily’s “Wuthering Heights” is often rated the greatest of the Brontë novels, while Anne, the youngest, produced “Agnes Grey” and “The Tenant of Wildfell Hall.”)

Charlotte’s life was assuming the grimness of Jacobean tragedy. Stoical, she soldiered on, enjoying at least a few glimmers of happiness. She published two more novels, “Shirley” and “Villette”; dined with literary peers such as William Makepeace Thackeray, and cultivated friendships with female writers such as Gaskell and Harriet Martineau.

Despite “a notable absence of suitable men,” Charlotte earlier had received — and rejected — two marriage proposals. Harman suggests a member of her publishing firm, James Taylor, likely also raised the possibility of marriage to a reluctant Charlotte before leaving for a multiyear sojourn in India and losing interest. And in 1852, largely in deference to her father’s wishes, she declined yet another proposal, this one from the long-suffering Irish curate Arthur Bell Nicholls.

But touched by Nicholls’ loyalty and devotion, she eventually changed her mind. However slow-burning, theirs, to Harman, was a poignantly real romance — love at last requited. Just months into the marriage, though, tragedy again struck: A disastrous pregnancy led to agonizing illness, killing her when she, like her mother, was just 38.

Charlotte Brontë’s end seems to have been harrowing. But at least Harman’s meticulous, affectionate biography reassures us that her afterlife is in good hands.

Klein, a cultural reporter and critic in Philadelphia, is a contributing editor at Columbia Journalism Review and a contributing book critic at the Forward. Follow her on Twitter @JuliaMKlein.

::

Charlotte Brontë: A Fiery Heart

Claire Harman

Alfred A. Knopf: 480 pp., $30

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.