Pfizer shows that its Allergan merger was only a tax dodge

- Share via

When it announced its record-setting $160-billion merger with Allergan, the maker of Botox, last November, the giant drug company Pfizer tried valiantly to pretend that the deal wasn't mostly about cutting its tax bill.

"We are doing this because of the strategic importance of the franchises, the revenue growth we believe we can get within the U.S. and internationally, and the importance to combine the research approaches," Pfizer CEO Ian Read told investment analysts on Nov. 23, after the merger was announced. He also said, a bit lamely: "I want to stress that we are not doing this transaction simply as a tax transaction."

I want to stress that we are not doing this transaction simply as a tax transaction.

— --Ian Read, Pfizer CEO, Nov. 23, 2015

Yet now that the deal has collapsed, one is forced to conclude that the driving force in the merger always was taxes. That's because all that's changed about Pfizer's and Allergan's business prospects since Nov. 23 is that the U.S. government put the kibosh on the tax savings. Both companies still have strategically important franchises, both could probably make more money together than apart, and both could theoretically gain from combining their research approaches. But all the talk of "compelling" synergies between these two companies now looks to be, in a word, flapdoodle.

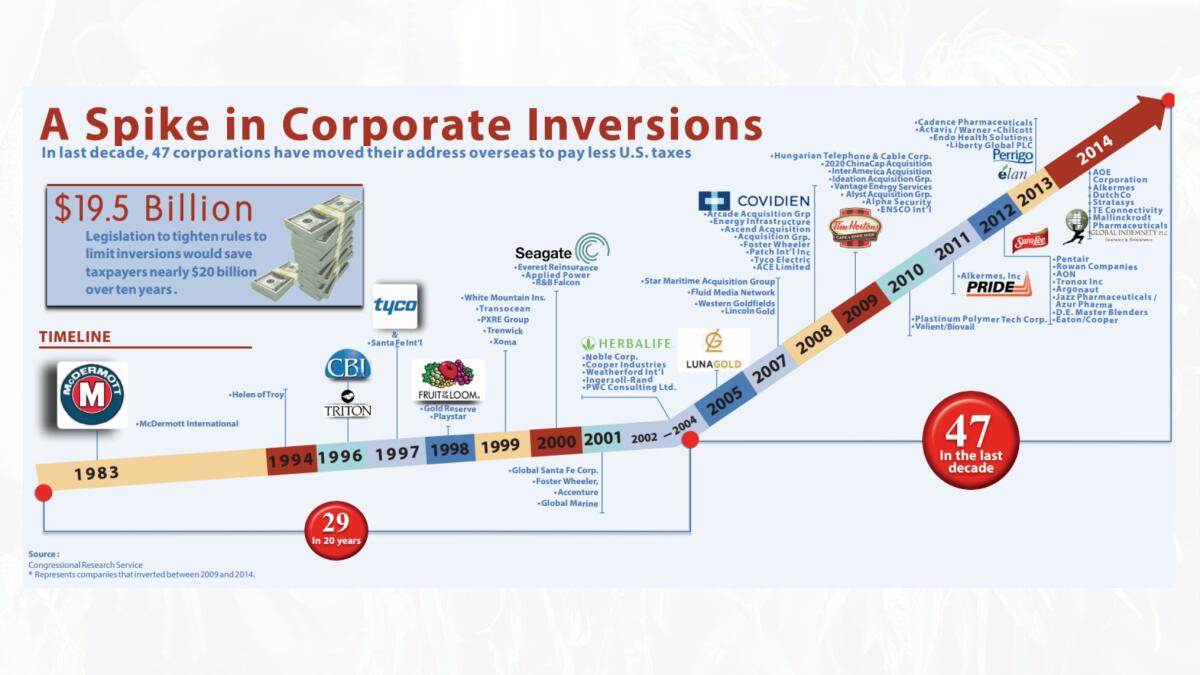

Here's the background. The merger was structured from the beginning as an "inversion." That's a transaction in which a smaller overseas company ostensibly buys a bigger U.S. company, after which the U.S. company moves its nominal headquarters to the smaller firm's home country. The key is that the corporate tax rate in the foreign country is lower than in the U.S. For example, Allergan is domiciled in Ireland, where the corporate tax rate is 12.5%. The U.S. top marginal federal corporate rate is 35%, though almost no company actually pays that, especially Pfizer. (More on that in a moment.) As it happens, Allergan's Irish domicile is the result of an earlier inversion deal, in which it was putatively acquired by Ireland-based Actavis. Its U.S. home is Parsippany, N.J.

Pfizer was a quintessential inversion candidate not merely because of its love for tax breaks, but because it also has about $148 billion in corporate profits parked offshore, according to a 2014 estimate by Citizens for Tax Fairness. The company could not repatriate this sum for use in the U.S. without paying U.S. taxes on it; but as an Ireland company, it could employ all sorts of maneuvers to use it without incurring full tax liability.

Inversions have attracted vehement denunciations from U.S. business watchdogs and U.S. politicians. They include President Obama, who blasted these financial fugitives as "unpatriotic," for pursuing "evasive tax policies" to exploit a "loophole." What makes inversions especially odious is that the U.S. companies typically don't move to the foreign home -- they keep their operations here, enjoying all the benefits of U.S. residency without paying their fair share of the costs.

I examined the tax advantages of Pfizer's proposed merger last year, after it was announced. I've also reported on the inversion craze here, here and here.

U.S. authorities have tried to attack inversions by tampering with technical regulations. Up to a point, this approach can be effective. Certainly it scored its biggest victory by destroying the Pfizer-Allergan deal. Under the old rules, a merger would not gain the full tax benefits of inversion if the shareholders of the larger firm ended up with more than 60% of the combined company. The deal was structured so that Pfizer shareholders would hold about 56% of the total.

But under rules issued Monday, the calculation of the size of the foreign firm had to ignore any acquisitions it made of U.S. companies in the previous three years. That's a period during which Allergan engorged itself through several inversions, including the Actavis deal. Subtracting those meant that the Pfizer shareholders would be deemed to own 80% of the merged company, nullifying the tax benefits.

The speed with which Pfizer canceled the merger underscores how little the "strategic" synergies of the deal really meant, compared with the tax benefits. Pfizer executives haven't bothered to explain why the Allergan merger wouldn't be worthwhile even without the benefits of inversion-driven tax savings.

That's unsurprising, in light of Pfizer's history of squeezing the tax code for advantages until it screams for mercy. Citizens for Tax Fairness and other sources have asserted that the company's effective tax rate, stated as 22.2% in its 2015 annual report, is effectively closer to 7.5%, thanks to international accounting stratagems. Even so, the company was estimated to be in line for $1 billion a year in tax gains if the Allergan merger went through.

The government's attack on the Pfizer-Allergan deal shows that it's serious about stemming inversions, but the question remains whether its approach is the best one. Tinkering with tax technicalities works in specific cases, but as USC tax expert Edward Kleinbard has argued (and as I reported here) a more lasting approach would be to attack inversions at the root -- by reducing the gap between the tax treatment of corporate income in the U.S. in comparison with the rest of the world. This would shut off corporations' incentives to play one country's tax regime against another's.

As long as the average tax rate paid by American corporations on foreign income is about 16.7% (according to a survey by two Dutch economists), while it's 5.6% in Ireland and 3.8% in Britain, corporate tax attorneys will try to earn their pay by looking for ways to capture the difference. Kleinbard believes that the right solution is "worldwide tax consolidation at a fair rate." That could mean reducing the U.S. corporate rate from 35% to somewhere in the mid-20s, he says, but the result will be a cleaner, fairer and perhaps even a more productive corporate tax.

Keep up to date with Michael Hiltzik. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see his Facebook page, or email michael.hiltzik@latimes.com

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.