Column: Allegations of a hospital chain’s ruthless price-fixing explain why you pay so much for healthcare

- Share via

When big hospitals merge, the merger partners’ mantra is almost always the same: The deal will deliver lower costs to the lucky patients, with no sacrifice in quality.

California Atty. Gen. Xavier Becerra has just fired a high-caliber bombshell into this argument. In a lawsuit filed at the end of March, Becerra alleged that Sutter Health, a nonprofit chain that is the dominant hospital system in Northern California, ruthlessly exploited its size and reach to extract “illegally inflated prices” from insurers, employers and patients.

Sutter’s market power, Becerra says, has driven up in-patient costs in Northern California to the point that they’re as much as 70% higher there than in Southern California. And that has “injured the general economy of Northern California and thus of the state.” Rising healthcare prices, Becerra observes, force wages lower or allow them to rise more slowly than they might otherwise. Sutter Health says Becerra’s filing is “factually inaccurate” and “fails to adequately account for Northern California’s robust and competitive health care environment.”

If you don’t allow employers or health plans to put more expensive facilities in a higher co-pay tier, you are undermining consumerism.

— Kristof Stremikis, California Health Care Foundation

Becerra’s lawsuit provides a window into the role played by the consolidation of healthcare providers in the nation’s stubbornly high healthcare spending. Sutter is not a unique case, though the allegations are so extreme they have led to a move in the Legislature to outlaw the system’s alleged practices.

“The pattern holds in many other parts of the United States,” says Kristof Stremikis, director of market analysis at the California Health Care Foundation. Becerra’s focus on Sutter Health and Northern California doesn’t suggest that Southern California is immune from the same trend, although none of Sutter Health’s 24 hospitals is located south of Santa Cruz. “Southern California is not unconcentrated, just a little less concentrated than Northern California.” Indeed, Southern California is becoming more concentrated via the growth of systems such as Dignity Health, a Catholic hospital system operating statewide.

Nor is Becerra’s lawsuit the first time that similar allegations have been launched against Sutter Health. The system is the defendant in a 2014 class-action lawsuit filed in San Francisco Superior Court, the same venue chosen by Becerra, making almost identical allegations. The case has been bogged down in procedural motions, and Sutter says it has not “had the opportunity” to present facts to disprove the plaintiffs’ allegations.

The case, initially filed by a health plan associated with the United Food and Commercial Workers union, involves at least 2,000 and as many as 9,000 employers and unions whose health plans contracted with Sutter since 2002, covering potentially millions of employees. The plaintiffs calculate that they may have overpaid as much as $700 million for services at Sutter facilities; under federal antitrust law, that could put the hospital system on the hook for up to $2.1 billion in damages.

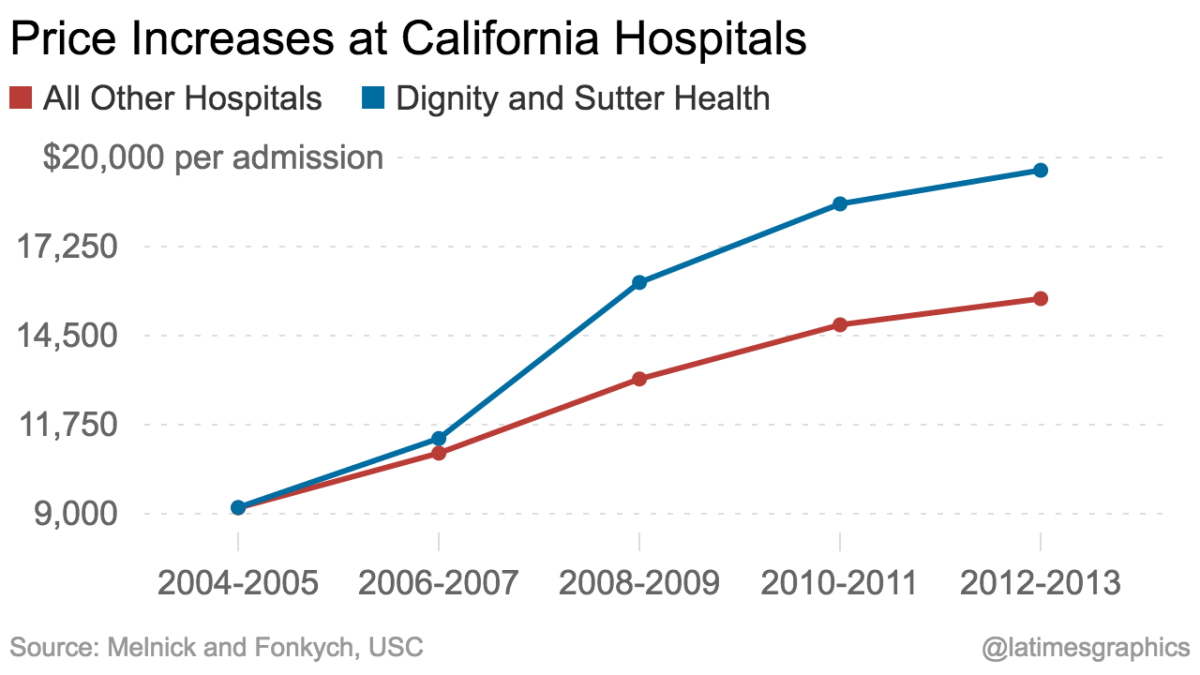

Sutter Health’s role in driving Northern California healthcare costs higher also has been examined by academic researchers and government analysts. A study published in 2016 by Glenn Melnick and Katya Fonkych of USC documented that while average prices per admission rose 76% for all California hospitals from 2004 through 2013, they rose 113% at hospitals that were part of the Sutter Health and Dignity Health systems. The data, they wrote, painted “a potentially troubling picture both for California and the rest of the country,” since the sharp run-up in hospital prices seemed to be “driven in part by increased market power by large, multi-hospital systems.”

And in 2008, the Federal Trade Commission staff reexamined Sutter Health’s 1999 acquisition of Oakland’s Summit Medical Center, which was located only 2.5 miles from its Alta Bates Medical Center in Berkeley. Summit’s prices had been lower than Alta Bates’, but after the acquisition, its prices shot up by as much as 72%, a rate that was “among the largest of any comparable hospital in California,” the staff found. “The merger of a higher-priced hospital with a lower-priced competitor produced two higher-priced hospitals.”

Sutter Health’s prices tend to draw competitors’ rates higher. “These guys set an umbrella price, and everyone else floats up,” Melnick told me.

What’s most interesting in the Becerra and class-action lawsuits is what they assert about how Sutter Health uses its size to immunize itself from competition. They highlight an “all or none” rule that Sutter began imposing in its contracts with health plans in 2002. Sutter wouldn’t allow any of its hospitals to be excluded, or even relegated to lower tiers that allowed patients to choose them at higher co-pays.

This poses a dilemma for payers, because many Sutter hospitals are “must-have” institutions for insurers or their clients, whether because they’re highly valued by patients because of their reputations, or are the only suitable hospitals within particular geographic regions. But the restriction prevents insurers or employers from steering patients to lower-cost hospitals, either by placing high-cost institutions outside the network or charging higher co-pays.

“If you don’t allow employers or health plans to put more expensive facilities in a higher co-pay tier, you are undermining consumerism,” Stremikis says. Healthcare experts are divided over whether using higher co-pays to steer patients away from some institutions or procedures necessarily produces better healthcare outcomes, but there’s no question that it reduces spending. Take away the option, and “you’re tying the hands of the health plan or employers to try to manage costs.”

Sutter Health told me through a spokeswoman that “health insurance companies are able to include or exclude parts of the Sutter Health system from their networks” and have been for many years. But that’s misleading at best.

According to testimony in the class-action lawsuit from Anthem, Blue Shield and other insurers, Sutter Health placed such punitive conditions on exclusions that payers typically gave up the effort. Among the conditions, according to declarations by insurers filed with the class-action case, was that the health plans would have to pay 95% or more of billed charges for any out-of-network services used by their members.

Since it was likely that some Northern California residents would end up at non-network Sutter hospitals at some point, chiefly via their emergency rooms, this was a major threat — Blue Shield determined that Sutter Health would collect a 270% profit over its costs for any services billed at that rate. For members of the Pacific Business Group on Health, a consortium of Northern California employers, “it is not economically feasible … to have a network that does not include Sutter facilities,” David Lansky, CEO of the group, said in a declaration, because it is not “economically feasible … to pay for Sutter’s services at non-contract, out-of-network rates.”

Among the other anticompetitive practices alleged by the attorney general and the plaintiffs in the class-action lawsuit is an arbitration and confidentiality agreement that insurers and, by extension, employers must sign to have access to in-network rates. The agreement prohibits employers from disclosing the Sutter Health contract to any third parties.

It should be plain that, as Becerra contends, there’s no “legitimate explanation” for price-fixing of this sort. It happens because Sutter Health has the ability to exploit its market position. Lawsuits are one remedy, but litigation takes time — the class-action case is in year four, with trial not expected to start until next year at least.

Legislation might be a better answer, in the form of a measure introduced in Sacramento by Senate Majority Leader Bill Monning (D-Carmel) that would flatly outlaw “all or none” contracts or confidentiality provisions.

Hospital mergers are a wave that won’t be receding anytime soon. But that doesn’t mean they have to lead to profiteering and rent seeking on the scale described by the allegations against Sutter Health. Not only their patients pay the price; we all do. That’s reason enough for regulators and legislators to step in.

Keep up to date with Michael Hiltzik. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see his Facebook page, or email michael.hiltzik@latimes.com.

Return to Michael Hiltzik’s blog.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.