No surprise: Conservative sneers that public employees like their pensions

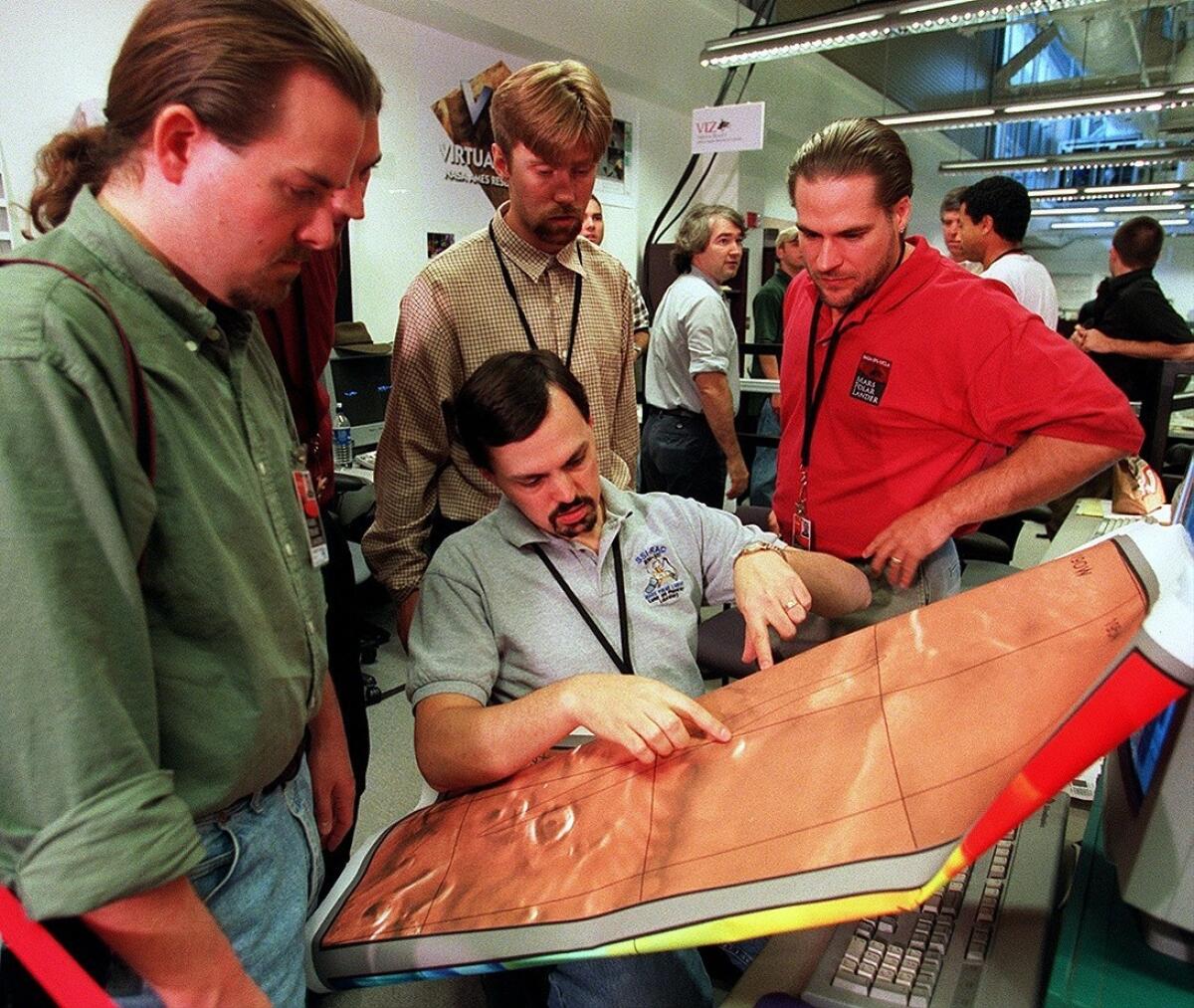

Typical public employees? UCLA scientist Mark Lemmon (holding map) and other planetary scientists at UCLA examining a map of Mars in 1999.

- Share via

A recent Gallup poll finding that public employees are happier than private-sector workers with their pension plans and other benefits has elicited a condescending response from the conservative American Enterprise Institute’s economics blogger, James Pethokoukis.

At least we think it’s condescending. His post is headlined: “No surprise: Government workers are way happier with their pension plans than private-sector counterparts.”

It’s possible, one supposes, that Pethokoukis thinks the superiority of public pension plans is a good thing, and that he’s implicitly arguing that private employers ought to meet the public sector’s higher pension standards in order to keep their employees happier today and comfortable in retirement.

But that’s unlikely, for it would run counter to his own employer’s general outlook on public pensions, which is that they’re overly generous. Most of his post is dedicated to quoting a 2014 screed by AEI’s pension expert, Andrew Biggs, who wrote that public plans turn many public workers into “pension millionaires.” (If you want an undistilled look at conservative hostility to public and, indeed, private workers, take a gander at the anti-union platform just released by Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker, a Republican who’s running for president.)

Gallup reported that 82% of government employees were completely or somewhat satisfied by their retirement plans, compared with only 57% of private employees. There was a similar divergence on health insurance and vacation time. Public and private workers showed fairly close levels of satisfaction (factoring in margins of error) on job security, wages and their bosses. Public workers tended to report slightly lower levels of satisfaction with the recognition they receive on the job and with stress levels.

Let’s turn to Biggs’ analysis, which Pethokoukis cites.

We can start with Biggs’ assertion about “pension millionaires,” which is based on calculations such as that “in Nevada, an average full-career state worker can expect to receive $1.3 million in lifetime pension benefits. Alaska, California, Colorado and Oregon all pay lifetime benefits exceeding $1.2 million.”

We’ll do Biggs the courtesy of not presuming that he intends these scary figures to mislead, although it’s hard to think of any other reason to use them. According to government statistics, the average 60-year-old can expect to live almost another 23 years; the average 65-year-old almost 20 more years. In other words, Nevada’s figures translate into average annual benefits of $56,500 to $65,000, California’s to averages of $52,000 to $60,000. It’s unclear if Biggs is using the present values of a two-decade income stream or just adding annual benefits together, but obviously an annual retirement income of $52,000 doesn’t sound as shocking as “lifetime” income of $1.2 million. If it did, here’s betting that Biggs would have used it. In any case, an annual income of even $65,000 won’t make anyone a “millionaire” in the conventional sense of the term.

Moreover, Biggs acknowledges that these are the benefits for “full-career” state workers -- that is, those who worked at least 30 years, and possibly more than 40, at their public jobs. “For employees who spend a career in state government,” he wrote, “generous pensions put retired public workers among the highest earners in their state.” But how representative are they of the public workforce?

The answer is, not very.

According to CalPERS, the California state retirement system, the average length of service for a state retiree is just under 20 years. The average annual benefit comes to between $32,800 and $36,000. CalPERS says its average member retires at age 60, so with an average life expectancy of 83, even the highest-earning average retiree will collect, over his or her retirement, $828,000--not quite a millionaire.

Biggs writes that in California, “a typical full-career worker retiring today receives $61,560, plus roughly $20,000 in Social Security benefits.” This requires some unpacking. To begin with, CalPERS says that 40% of its members don’t receive Social Security; indeed, public employees are the last remaining category of worker in the U.S. to be exempted from Social Security in large numbers. (CalPERS doesn’t say so, but many government workers who do receive Social Security get pared-back benefits, thanks to a curious formula for their benefits that long has been crying out for revision. We reported on that here.)

In other words, it’s hard to create a “typical” California retiree who receives Social Security benefits, since 40% of them don’t.

The real tilt in Biggs’ analysis is the focus on “full-career” workers. Treating them as typical inevitably misrepresents the overall picture of public employee pensions. But it’s not unusual in conservative circles. Consider an analysis by the anti-public union California Policy Center, which wrung its hands over the lavish pensions earned by California employees by citing extrapolations of those real-life 20-year service averages to careers of 30 or even 43 years. And why not? If the average actual CalPERS pension of $33,653 seems reasonable enough, why not cite the pension for the average 43-year employee, $70,040. Never mind that the latter appears to be a rare, if not largely mythical, beast.

Another trick used by critics of public employees to make their compensation appear unduly lavish is to compare them to pensions in the overall U.S. workforce. But the workforces aren’t comparable. Public employees typically are older (that is, more experienced), have more advanced education and, according to the Congressional Research Service, are more likely to be employed in higher-paid “management, professional, and related occupations,” 56.2% to 37.8%.

It may be fashionable to think of the typical public employee as a hallway sweeper at the DMV, but the reality is they’re teachers, professors, scientists and administrative workers. (Biggs, to his credit, leaves public safety employees such as police and firefighters, who often collect the most generous pensions, out of his calculations.) More than 25% of all public employees are in education or related occupations; in the private sector, that share is 2.3%.

The question raised by the Gallup survey is why public employees are so much happier with their retirement benefits than their private-sector counterparts. Gallup implies that the reason isn’t so much that their benefits are higher, but that they’re more dependable.

“Many government workers likely have pension plans -- something increasingly rare in the private sector,” the survey firm says. By this Gallup means traditional defined-benefit pensions, which are based on years of service and average pay. They differ from defined-contribution plans such as 401(k) plans, which are based on how much the employee and employer contribute, but are vulnerable to market downturns and typically underfunded by the worker’s own (unwise) choice.

Defined contribution plans have their virtues, but as a complete substitute for defined benefit plans--the trend in the private sector--they’re leaving millions of Americans unready for retirement. As Pethokoukis says, it’s “no surprise” that public workers are happier with their plans--in fact, it’s a testament to their wisdom.

Keep up to date with the Economy Hub. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see our Facebook page, or email michael.hiltzik@latimes.com.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.