Who are the 1 percent? Two new views

- Share via

Nobel Prize-winning economist Robert M. Solow has leveled a blast at a recent attempt by Harvard economist N. Gregory Mankiw to explain rising income inequality and the primacy of the 1% in the U.S. as the result of “just deserts” going to the talented people making important economic contributions to society.

The tenor of Solow’s approach can be gleaned from the opening words of his piece, which fault Mankiw’s analysis for its “unstated premises, dubious assumptions and omitted facts.”

Mankiw, in his return fire, dismisses Solow’s attack as “scatter-shot.”

The exchange, which appears in the latest issue of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, was prompted by an article by Mankiw last year in the same journal titled “Defending the One Percent.” Since the complaints of the one percent that they are woefully misunderstood and unfairly, even dangerously, targeted for obloquy is big these days (I’m talking about you, Tom Perkins), it’s worth taking a look at what these two creditable economists have to say about the topic.

Mankiw is a former chief economist for the George W. Bush administration and an advisor to the Mitt Romney campaign. He fashions himself a “new Keynesian,” in which guise he spoke out strongly against the stimulus package of 2009. Solow occupies the other end of the philosophical spectrum; he was a senior economist for John F. Kennedy. He’s an emeritus professor at MIT, and his 1987 Nobel was for his work on theories of economic growth.

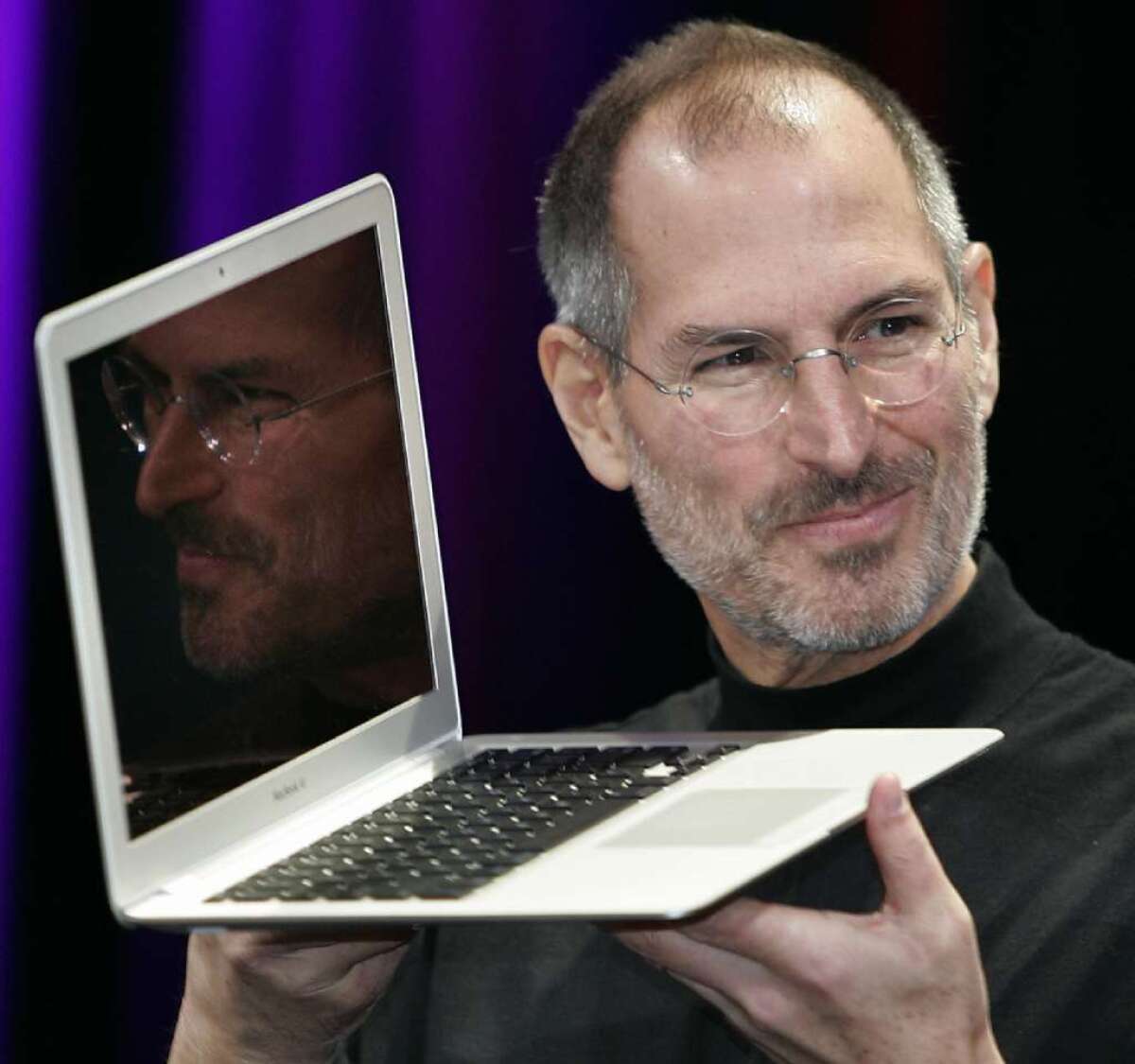

Mankiw’s original article treated income inequality as an artifact of entrepreneurship. “Think of the entrepreneur as Steve Jobs as he develops the iPod, J.K. Rowling as she write her Harry Potter books, or Steven Spielberg as he directs his blockbuster movies,” he wrote. “When the entrepreneur’s product is introduced, everyone in society wants to buy it.... The new product makes the entrepreneur much richer than everyone else.”

These newly rich, he wrote, “have made significant economic contributions, but they have also reaped large gains. The question for public policy is what, if anything, to do about it.”

Solow doesn’t buy that the “One Percent consists mainly of entrepreneurs whose innovations generate a lot of consumer surplus for the world. There would be less alarm if that were so.” Extreme inequality, he says, “is not primarily about useful entrepreneurs.”

A more important source of inequality, he says, is the capture of excessive income and wealth--”rents,” in economic parlance--by the financial industry, particularly the trading sector. That sector is innovative, he allows, “but socially productive innovation, no thanks.”

Solow faults Mankiw--fairly, we think--for largely ignoring the “most dangerous adverse consequence of extreme inequality”--the growing political power of the rich, especially since the Supreme Court took the brakes off campaign contributions in its infamous 2010 Citizens United ruling.

Mankiw in his reply says that he’s not very worried about the political influence of the rich. There are billionaires on both sides of politics, he says--the Koch brothers on the right, George Soros on the left--and after all, the nation elected a left-leaning president “committed to raising taxes on the rich.”

This is weak of Mankiw. For one thing, leaving aside the fact that conservative millionaires have consistently outspent liberals, the point is what the money is spent for.

The Koch brothers and their fellows are agitating for things like less industry regulation, less taxation and fewer government programs, most of which benefit the middle- and working class and the poor; Soros’ pet issues have included the empowerment of minority and disadvantaged communities, get-out-the-vote campaigns, immigration reform, including amnesty for undocumented immigrants, and the causes of the ACLU. (These descriptions come from a conservative website attacking Soros.) Are these equivalent expressions of social action? We leave it to the reader to judge.

As for the “left-leaning president,” his commitment to raising taxes on the rich was not nearly as strong as many progressives wished, and in any event much of that program was blocked by conservatives in Congress financially supported by millionaires on the right.

The debate over economic inequality continues, but one thing is plain: notwithstanding Mankiw’s depiction, the typical one-percenter resembles not Steve Jobs, but Jamie Dimon.