Scouting for trout

- Share via

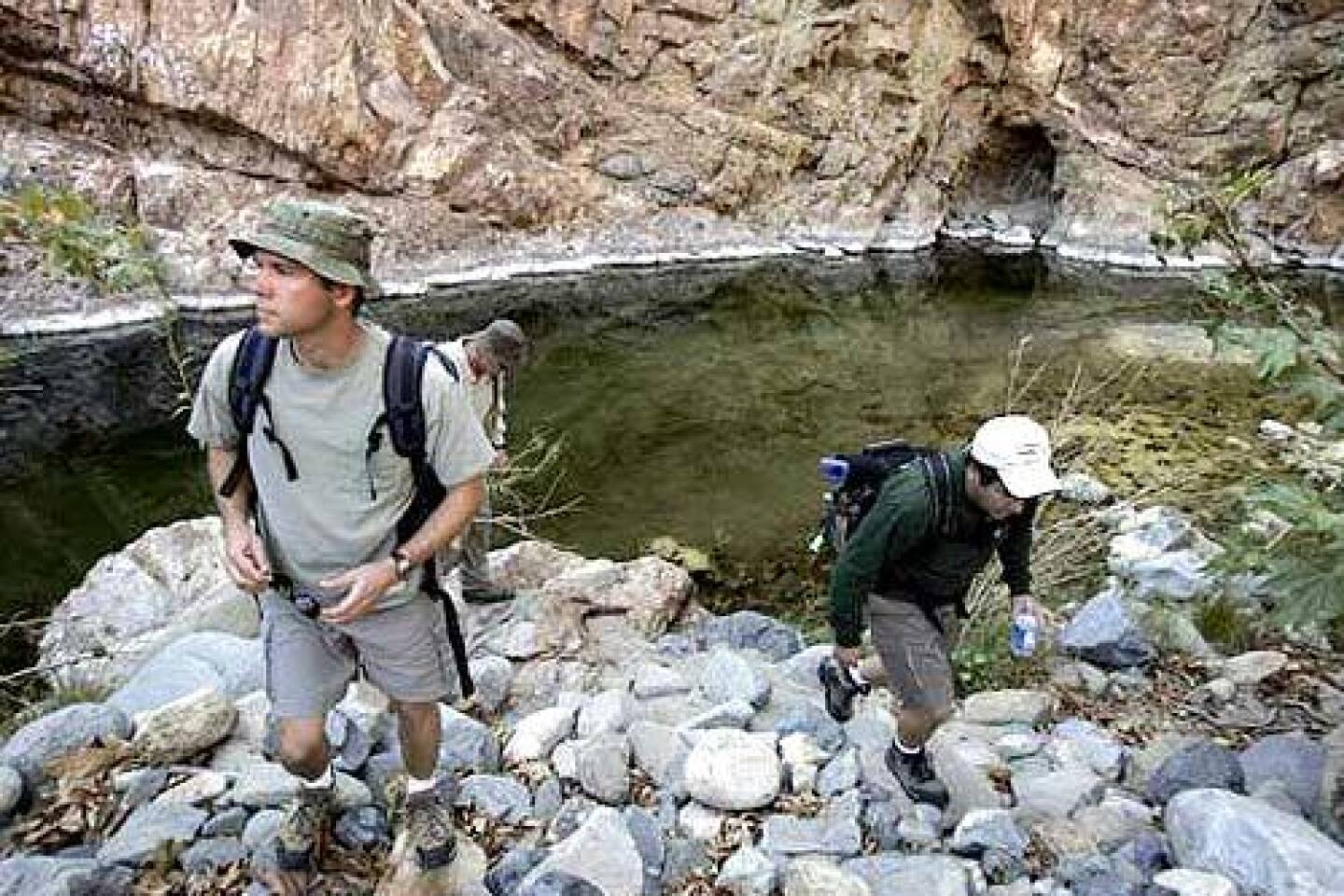

DEEP in the San Mateo Canyon Wilderness near San Clemente, the rocky floor of Cold Spring Creek is the only path through a jungle of chaparral. Poison oak covers the banks, blackberry vines form trip wires, Africanized honeybees buzz around.

The creek bed steepens, and for a trio of conservationists negotiating precipitous dry cascades and dense vegetation, it feels more like rock climbing than hiking.

FOR THE RECORD:

Steelhead trout —A map with an article in Tuesday’s Outdoors section about steelhead trout showed a location that was labeled as Mission Viejo. It should have been labeled as the Cow Camp at Rancho Mission Viejo.

“Rattlesnake!” Michael Hazzard yells, as the snake, just a few feet away, crosses the path, rustling fallen leaves before it disappears into a crevice.

“Close one,” says Ed Schlegel, who steps over it. “I didn’t even see it.”

Hazzard, 48, a Trout Unlimited official, orders his tiny column of bushwhackers to take a five-minute break. Sweat beads on his forehead as he gulps from a bottle of lemon-lime Gatorade. It’s 93 degrees and this is no ordinary fishing trip.

Hazzard; Schlegel, a 63-year-old member of the Surfrider Foundation; and Mike McDermott, 56, a U.S. Forest Service volunteer, are on their way to Devil Canyon, a remote and jagged gorge on the northeast border of Camp Pendleton Marine Corps Base. It is one of three weekend expeditions this summer by crews searching for the nearly extinct southern steelhead trout — a game fish once so plentiful in local rivers and streams the daily limit was 50.

A steelhead was last discovered in Devil Canyon in December 2003, when a California biologist found a lone adult that survived three years of drought swimming in a quiet pool. Budget cuts at the state Department of Fish and Game force the agency to rely increasingly on volunteers in the search for the fish.

“These guys are hard-core. They are my eyes and ears. We’d have a hard time doing the job without them,” says Department of Fish and Game biologist Tim Hovey, who also ventured into the wilderness on a summer trip with biologists John O’Brien and Jim Asmus.

Anglers prize steelhead for their beauty, power and meat; catching one is considered the apex of freshwater fishing. Yet so few southern steelhead remain that the federal government declared the fish, found along the Southern California coast, an endangered species in 1997.

“The first time you hook one up, it’s lightning striking your pole,” says Jim Edmondson, conservation director of California Trout. “They are tenacious, spirited fish. They refuse to give up. It’s an experience you carry for the rest of your life.”

The trekkers are not trying to catch steelhead. They carry no rods and reels. Instead, they lug snorkel and dive gear through the brush, hoping to catch a glimpse of the fish in a pool or riffle to show it has a toehold in the southernmost extent of its range. There hasn’t been a confirmed sighting in these waters since 2003.

“You really got to believe to do this work,” says Hazzard, who has made scores of trips into the backcountry in search of the legendary fish. “The exciting thing about being there is you just don’t know where they are. You could walk around a corner and jackpot.”

*

Reason for hope

HAZZARD is upbeat because San Mateo Creek burst the sand berm at the Trestles surf spot during last winter’s rains, opening a path for fish migrating from the ocean. There were unconfirmed reports of steelhead at the river mouth. Some might have made it to Devil Canyon to spawn — a swim of eight miles or more.Like salmon, steelhead hatch and grow in freshwater, migrate to the ocean and return to streams and rivers to spawn. Unlike salmon, they don’t die afterward. They look like rainbow, grow 30 inches long or more with silver sides and dark blue-gray backs. The southern species of the fish is so hardy that some people say it can live under a yucca tree.

For the men seeking the fish, the journey into Devil Canyon begins in late summer with a three-hour drive over Ortega Highway in south Orange County and dirt roads winding through the Cleveland National Forest. They spent the night under oaks at vacant Cold Spring Ranch, where Hazzard prepares breakfast on a propane stove: scrambled eggs, bacon, potatoes, fruit and coffee. The aromas fill the air.

“It’s going to be 100 degrees today,” Hazzard says, handing out bananas. “You’re going to need the potassium. Don’t forget to drink lots of water.”

Hazzard, a stocky man from San Juan Capistrano with neatly trimmed brown hair, is a part-time carpet cleaner and full-time environmentalist. He became interested in steelhead in 1999, after Toby Shackelford, a classmate at Saddleback College, caught one on San Mateo Creek, half a mile from the ocean.

It was the first confirmed steelhead on the stream in more than 50 years, a catch that led to sightings of more than 40 fish in the creek.

“I was immediately taken by this,” says Hazzard, who fished on the Kern River as a youth in Bakersfield. “I had no idea trout were here or how bountiful San Mateo Creek used to be.”

Since then, he has made at least 60 hikes — many of them lasting 10 to 15 hours — in the mountains around San Mateo Canyon Wilderness. On the 19th outing, he saw his first steelhead in San Mateo Creek, but the fish were gone by summer 2000.

San Mateo Creek is one of Southern California’s last free-flowing streams. It starts about 20 miles inland in the Cleveland National Forest and runs through wilderness before entering Camp Pendleton seven miles from the ocean.

If Hazzard and his team can find more fish, it might help opponents of a proposed Foothill South toll road, which would cross San Mateo Creek near the estuary. Sediment generated during construction and polluted runoff from the highway could threaten the species.

“The Foothill South is completely incompatible with steelhead recovery,” Hazzard says. “At stake is the last clean watershed in Southern California.”

Furthermore, evidence of steelhead could help clear the way for more research, fish ladders to help steelhead spawn upstream and elimination of nonnative species that compete with steelhead. Trout Unlimited, California Trout and San Diego Trout have secured at least $800,000 in government grants and are working to remove Rindge Dam near Malibu and Matilija Dam near Ojai so that fish can reach backcountry spawning grounds.

“We have a good chance to restore southern steelhead in the next 10 to 15 years,” says George Sutherland, who runs the steelhead recovery team for Trout Unlimited. “I might not catch one in my lifetime, but someday someone’s children will.”

*

‘The staircase’

AFTER breakfast, Hazzard and Schlegel pack their gear as McDermott, eager to start, departs for Cold Spring Creek, which leads to Devil Canyon.At 9 a.m., Hazzard and Schlegel start hiking down a dirt road to the jump-off point, a bald spot on a ridge. Despite the heat, they wear gloves, pants, boots, wide-brim hats and long-sleeve shirts to protect against ticks, poison oak, rattlesnakes and sun.

The first leg of the hike is down a trail that burrows though a tunnel of 10-foot-tall chaparral, where it is refreshingly cool beneath the canopy. The path ends more than a mile later at Cold Spring Creek, where Hazzard and Schlegel drop into the steep rocky stream bed. Hazzard calls it “the staircase.”

Footing is unstable on the cobbled floor, and blackberry vines crisscross the streambed and trip feet. Ferns grow 6 feet high, and sycamore and oak shield against the intense sun. It smells of mint, and running water gurgles under rocks.

It takes almost four hours to reach the junction of Devil Canyon and Cold Spring Creek. Tall sycamores stand at the confluence. So much water is running in Devil Canyon Creek it cools the air to 80 degrees or so.

“Welcome to the river Styx,” McDermott says. He rests on a rock in the middle of the creek and awaits the other hikers.

Green, red and cream-colored rocks mark the walls of Devil Canyon and rise 50 to 60 feet above the water. Cactuses dot the rock, their silvery needles sparkling in the sun.

Pressed for time, Hazzard and Schlegel quickly eat lunch. The 2 1/2 -mile hike took longer than expected, reducing the time available to snorkel in the creek and take samples.

Hazzard hikes up Devil Canyon to explore pools that may contain steelhead and finds a 50-foot-long stretch of creek so still it reflects canyon walls. Insects dart overhead, oaks shade the surface, the water is cool and the gravelly bottom is suitable for spawning, but it’s not deep enough for steelhead. There is no sign of the fish or grooves they make on the bottom to lay eggs.

Hazzard and Schlegel discover a second large pool upstream at the base of a 60-foot cliff. An oak shades the water, but there are no steelhead.

The results are the same farther upstream, where a chain of pools harbors cool, shallow water. Still no steelhead.

Running out of time, Hazzard and Schlegel climb back up Cold Spring Creek for the 3 1/2 -hour return trip. Both want to be back by dark, but McDermott stays the night to head down Devil Canyon Creek the next day.

Hazzard and Schlegel are exhausted but undaunted as they walk back to their car at Cold Spring Ranch. In the fading light, they toast the trip with cold beers from an ice chest.

“I definitely want to come back. This whole area contains suitable habitat,” Hazzard says. “If anything, this has just whetted my appetite.”

The odds of finding steelhead may be slim, but the elusive and tenacious fish has a way of showing up when least expected, silver ghosts that appear suddenly, perhaps after the next rainy season.

*

Dan Weikel can be reached at outdoors@latimes.com.

*

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX)

Snapshot / Steelhead trout

(Oncorhynchus mykiss)

Coloring: Steel blue with black spots on upper body; males have a reddish-orange stripe.

Habitat and diet: Steelhead need clear freshwater streams to spawn. At sea, they stay near the surface and eat squid, small fish and crustaceans.

Steelhead vs. rainbow: The steelhead is a rainbow trout that has migrated to the ocean. It returns to rivers and streams to spawn. Unlike salmon, steelhead can make the transition between fresh- and saltwater several times.

--

Shrinking range of the steelhead

Wildlife experts say steelhead trout flourished up through the early 1900s in local waterways, including San Mateo Creek, but have all but disappeared since the 1960s.

--

Sources: https://www.caltrout.org/steelhead ; NOAA; Washington state Department of Natural Resources, ESRI

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.