With ingenuity and a 3-D printer, group changes lives

Led by a film producer with no engineering background, Not Impossible tackles the physical limitations that arise from blindness, paralysis and other conditions.

- Share via

Mick Ebeling arrived in Sudan with little more than a toolbox, rolls of plastic and two microwave-size 3-D printers.

He had endured a weeklong journey from Los Angeles, with stops in London, Johannesburg and Nairobi before reaching Juba, the capital of South Sudan. From there, he flew on a small twin-engine plane to Yida, where at a refugee camp he found Daniel Omar.

Ebeling had read a magazine article a few months earlier about the 16-year-old, whose hands and forearms had been blown off two years ago during an airstrike launched by the Sudanese government. The boy's plight resonated with Ebeling, who tracked down the remote hospital where Daniel had received treatment. Over Skype, Ebeling told Daniel's doctor: I think I can help.

After meeting in Yida, Ebeling and Daniel caught an 11-hour ride in the back of a Land Cruiser to Gidel, Sudan, a volatile region in the Nuba Mountains where Daniel's doctor tends to amputees and other victims of the civil war plaguing the country.

In a small tin shed, Ebeling connected a 3-D printer to a laptop. The printer began melting plastic to form three-dimensional pieces, which he then joined together like Legos. He worked off a design created by a carpenter friend who, after accidentally severing four fingers with a table saw, had built his own prosthesis.

It took two days for Ebeling to print and construct a skeletal plastic hand bolted to an arm-like cylinder. Nylon cords attached to each plastic finger snaked up the length of the apparatus so that when the wearer flexed his or her elbow, the cords tightened and pulled the fingers into a fist.

Once the prosthetic device was fitted to Daniel's upper arm, the boy was able to wave, toss an object and feed himself with a spoon, major feats for someone who had been forced to rely on others for the most basic everyday tasks.

It was, Ebeling recalled later, "on par with watching my kids being born."

Ebeling didn't set out to be an inventor.

A Hollywood producer, he works on television shows, commercials and films, most notably executive producing the opening title sequence for the James Bond movie "Quantum of Solace." The 43-year-old graduated from UC Santa Barbara with a degree in political science. He has no medical or engineering background and no formal training in designing or building prosthetic devices.

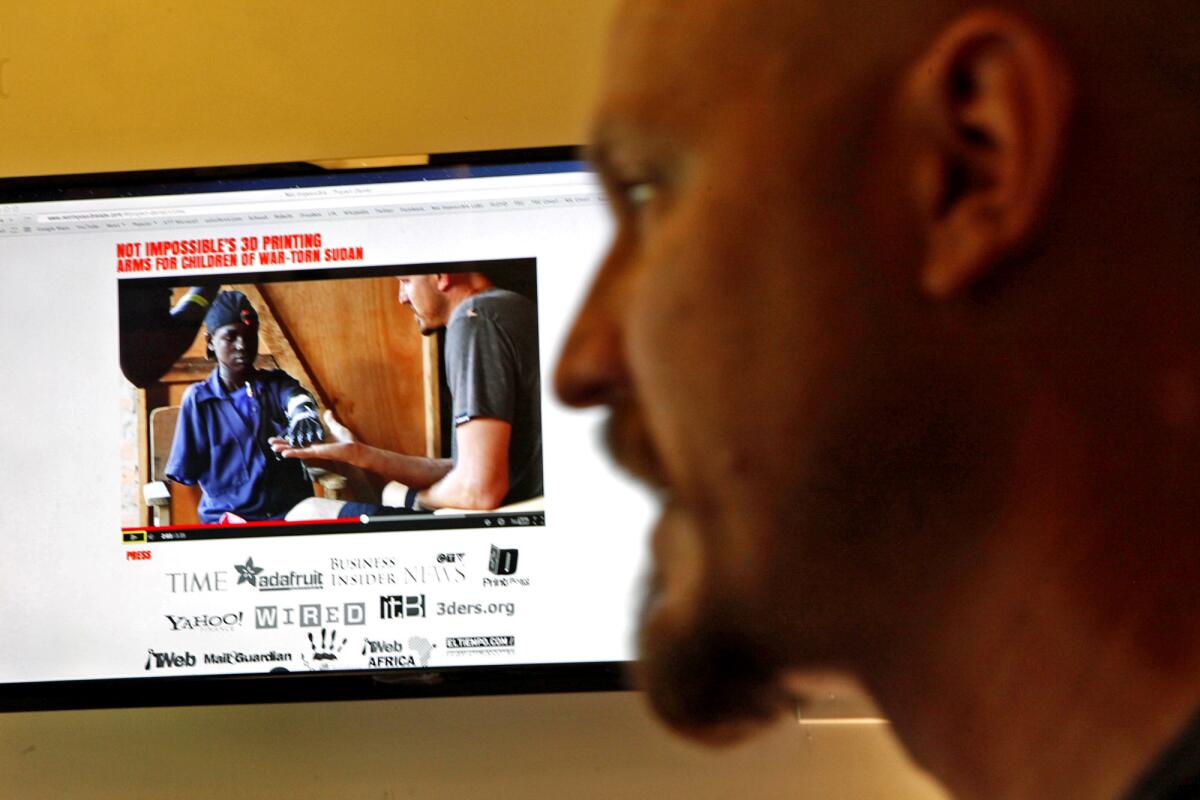

Mick Ebeling, founder and chief executive of Not Impossible, watches a film that features him fitting a prosthetic arm on Daniel Omar, a 16-year-old victim of the civil war in Sudan. (Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times) More photos

But today, Ebeling finds himself the unlikely leader of a team dedicated to tackling the physical limitations that arise from conditions such as blindness and paralysis.

The group calls itself Not Impossible. Volunteers work out of a bungalow tucked behind the Venice Beach home that Ebeling shares with his wife and their three boys.

"This is our equivalent of the Hewlett-Packard garage," he says of the light-filled two-room space with mustard-colored walls and wood-beam ceiling. A towering bookshelf brims with books and thick binders. A 3-D printer sits on a shelf in the corner. A large wooden table is covered with prototypes of prostheses and bags of screws. And on a white piece of paper tacked to a wall, someone has scrawled the word "impossible," with a red X slicing through the first two letters.

Ebeling's unexpected foray into making medical devices began in 2007, when he attended a benefit for a graffiti artist who had been diagnosed with Lou Gehrig's disease. Over time the artist, known as Tempt One, had become trapped in his paralyzed body, unable to speak, gesture or draw.

At first, Ebeling considered donating money for Tempt's healthcare costs. But after meeting with the artist's father and brother over lunch in Los Angeles, he pledged to do more.

He reached out to engineers he met at a design conference, pitching them on the idea of building a low-cost eye-tracking system. The end result: the EyeWriter, a pair of glasses affixed to a Web camera that enables people to draw on a computer with their eye movements.

Using the device, Tempt was able to create graffiti art again.

The EyeWriter was named one of the 50 best inventions of 2010 by Time magazine, and a TED talk that Ebeling gave on the glasses received more than 850,000 views after it was posted on the nonprofit's website. A team from Samsung contacted Ebeling to say it was building its own version based on the EyeWriter's design.

Mick Ebeling, founder and chief executive of Not Impossible, at his desk with prosthetic arms and hands that he created with his 3-D printer at his office in Venice. Ebeling is the unlikely leader of a team dedicated to tackling the physical limitations that arise from conditions such as blindness and paralysis. (Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times) More photos

"Thank you for your idea," a Samsung Creativity Lab team member in South Korea wrote in an email to Ebeling. "It inspires us and let us to help people in need."

The success of the EyeWriter led to the official formation of Not Impossible, a community of about two dozen innovators — PhDs, engineers, physical therapists, designers and computer programmers — from around the world who drop by the Venice bungalow or videoconference in for brainstorming and hacking sessions.

They're now tinkering away on the BrainWriter, a device that reads brain waves and eye movements to engage and disengage a computer mouse, and the Alex Mouse, a mouth-controlled joystick that enables quadriplegics to operate a PC. There's also the Chad Cane, which uses ultrasound to warn people about obstacles in their surroundings.

Ebeling is the ideas guy, coming up with a concept but then leaning on others with more expertise to execute it.

"I like to call him the action figure. He rallies people together," said Elliot Kotek, Not Impossible's chief of content.

Ebeling sees the world simply: If there's a problem, he wants to fix it. His parents were philanthropists in Phoenix, where he grew up, and he fondly recalls watching them open a shelter for abused women and a clinic that provided free healthcare to single working mothers.

"The best way to motivate me is to tell me no," he said. "It's a childish reaction, but it's who I am."

The plan is to eventually make Not Impossible's products available for purchase online and in stores. Ebeling's goal is to go a step further by putting the ability to build the gadgets into the hands of individuals who have no engineering know-how.

The best way to motivate me is to tell me no.”— Mick Ebeling

To prove that such devices are simple to make, Not Impossible is making its inventions open source: The software is available to anyone free of charge.

People who want to create their own EyeWriter, for instance, can visit Not Impossible's website to download the software and view a list of materials, many of them found in typical households. "Here's what else you'll need: 1x cheap sunglasses, 1x webcam, 1x floppy disc, 1x wire hanger, 1x wire cutters...."

The site then provides a four-step video tutorial on how to build the device. Total assembly time: as quick as one hour.

Ebeling took that teach-a-man-to-fish approach with him on his two-week Sudan trip in November, training Daniel, his doctor and eight refugees on how to print and assemble prostheses using donated laptops and 3-D printers that Ebeling left behind.

"We didn't want to show up and be the white savior," Ebeling said. "You know — show up, do a food drop, take a couple pictures with some starving African kids and then … hopefully upgrade to business class with miles on the way back and sip champagne."

Mick Ebeling, founder and chief executive of Not Impossible, rests his hands next to a prosthetic hand he created with a 3-D printer at his office in Venice. Besides making prostheses, the group developed EyeWriter, a pair of glasses affixed to a Web camera that enables people to draw on a computer with their eye movements. (Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times) More photos

When 3-D printers first became available, critics predicted the machines would be relegated to producing cheap novelty items.

But enthusiasts have touted the possibilities and say that as prices drop, the printers could one day become as ubiquitous as television sets or tablet computers; soon consumers may be able to print food, clothing and jewelry from their homes.

The printers "print" objects by melting material — usually plastic but sometimes metal, clay and even chocolate — and building it up layer by layer based on a computer-generated design.

They have already found a promising niche in healthcare. A British surgeon implanted a 3-D printed pelvis in a man who suffered from a rare form of bone cancer. Ear doctors have made custom hearing aids. A woman paralyzed from the waist down after a skiing accident received a 3-D-printed robotic suit that helped her walk again.

Richard Van As, the carpenter and Not Impossible member whose self-designed prosthetic fingers served as the prototype for Daniel's device, said people assume the technology is more complex than it actually is.

"Everybody seems to say, 'Oh, are you an engineer?' That doesn't matter," Van As said in Venice on a recent morning, wearing a T-shirt printed with the words "International Arms Dealer — in a good way."

In Sudan, he said, "people haven't seen a screwdriver, they haven't seen a drill, then Mick arrives and he's got 3-D printers and it's so simple."

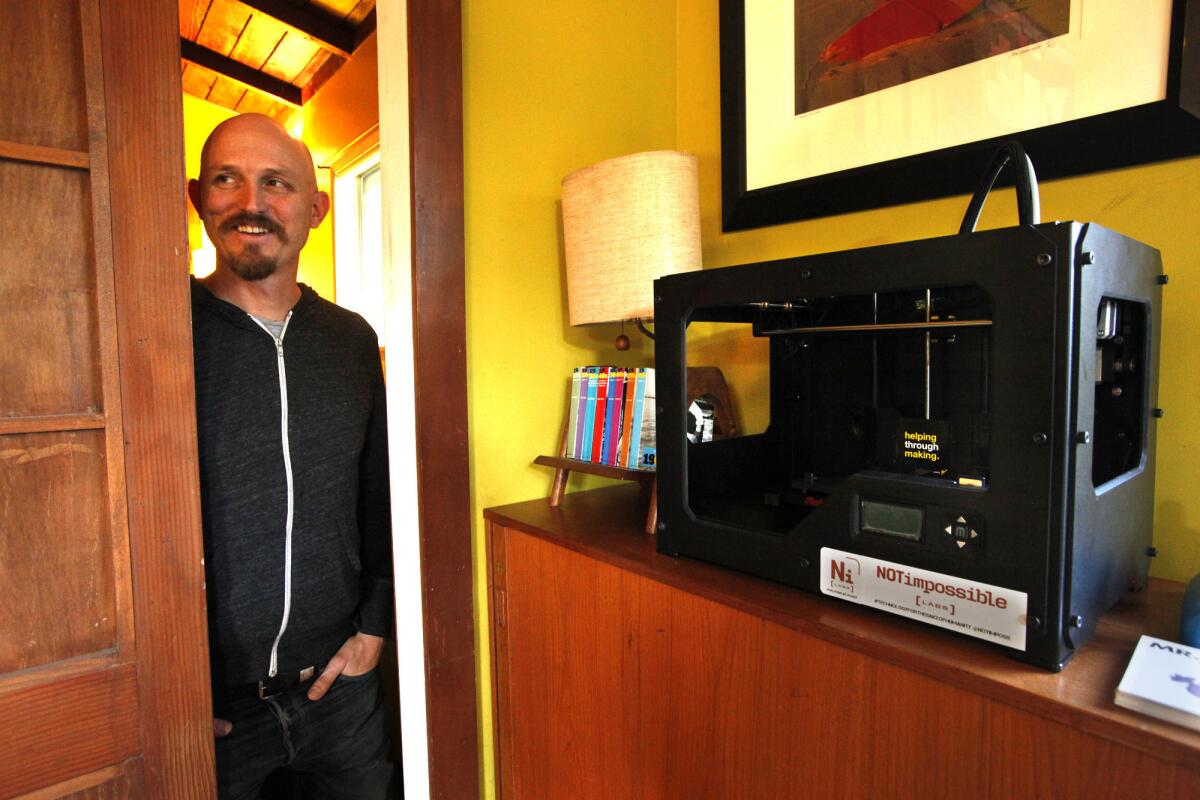

Mick Ebeling with a 3-D printer at the Venice office of Not Impossible. Ebeling, a Hollywood producer, is the group's ideas guy. He comes up with a concept but then leans on others with more expertise to execute it. (Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times) More photos

To help cover the cost of Not Impossible's projects, Ebeling accepts donations and enlists corporate sponsors. Intel and Precipart sponsored Project Daniel by providing laptops, tablets and funding for the trip to Sudan.

In return, Ebeling put his Hollywood background to use, bringing along a small film crew to record the trip and produce a video that the sponsors promoted on their websites.

Project Daniel is not without its challenges.

Although the materials needed to make Daniel's prosthetic hand and arm cost about $100, 3-D printers are still expensive — a few models are now priced at less than $500, but most cost thousands of dollars.

The prostheses aren't perfect: The hands are able to perform rudimentary tasks, but more precise movements are tricky or out of the question.

The project has also garnered skepticism from medical professionals.

Matthew Garibaldi, director of orthotics and prosthetics at UC San Francisco, said he was aware of Not Impossible and other grassroots groups tackling similar prosthetic projects.

"I've seen the results of some of these, and they've been moderate results at best," he said. The key is to develop prostheses that are "inexpensive and highly functional — these two pieces haven't really been married yet."

Ebeling said that for people like Daniel living in war-torn parts of the world, the return of basic motor skills is invaluable.

"He got a part of himself back," he said. "To me, this is technology for the sake of humanity. He's feeding himself now; he's a step closer to taking care of himself; he's regaining his independence. Now he's one step closer to self-sufficiency."

Follow Andrea Chang(@byandreachang) on Twitter

Follow @latgreatreads on Twitter

More great reads

In Syria, war is woven into childhood

We have become reliant much more on kids like that. But this is not a good thing.”

Ex-lawyer is on a mission to keep schools fair

A large number of school districts were quite brazenly ignoring the law.”

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.