Digital technology lets libraries share their fragile treasures with the world

- Share via

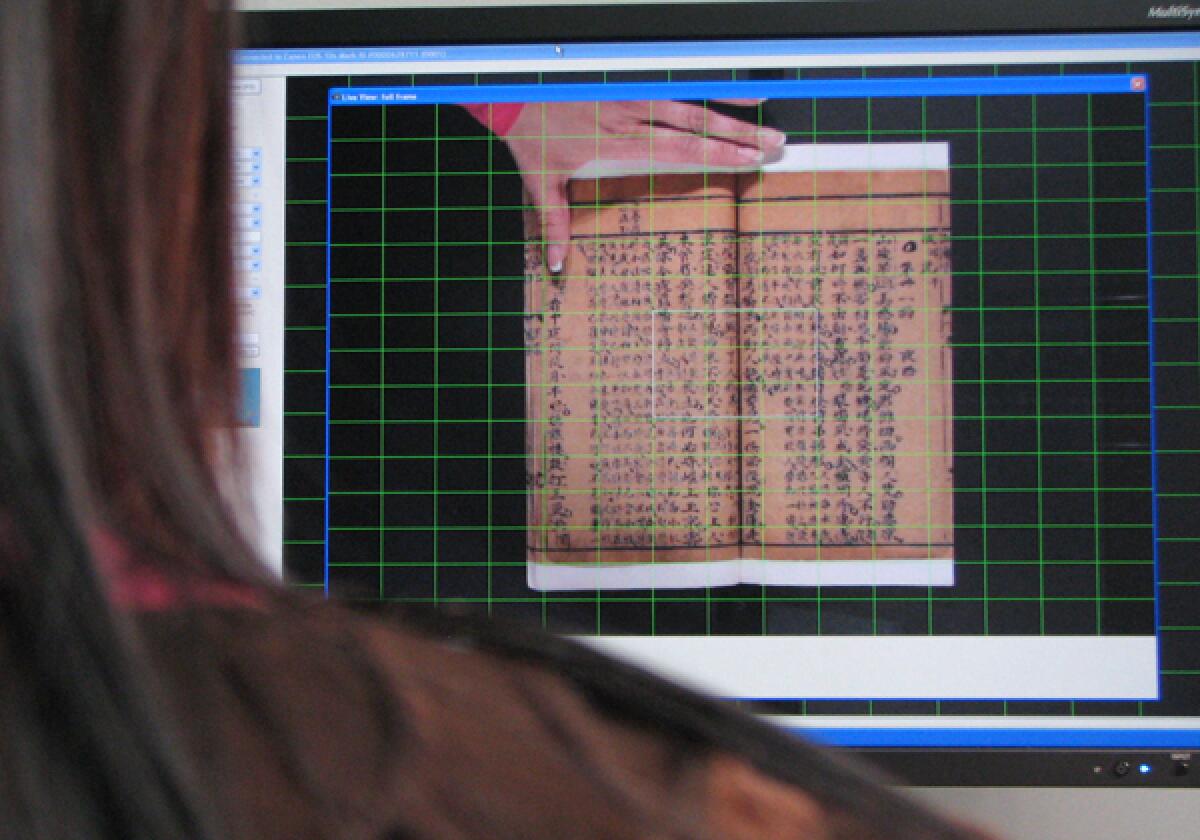

Recalling a medieval scribe laboring to preserve humankind’s rarest writings, Edith Young gently places each fraying page of a 400-year-old Chinese manuscript on a special cradle before she lowers a glass plate to flatten it for a digital snapshot.

Young, a technician in Harvard University’s digital imaging laboratory, will repeat the step close to 100 times to create a digital record of “Story of Red Plum Blossom,” a Chinese drama written in the early 1600s that for the most part had been rarely seen except by a handful of museum curators and researchers.

Equipped with imaging equipment far more powerful — and often less expensive — than a decade ago, libraries of all sizes are transforming their physical collections into virtual ones. The ultimate goal is to digitize troves of books and documents long hidden in basements and to share them with the world in electronic form.

“Name an institution, and if they have books they’re looking to digitize them,” said Nick Warnock, president of Los Angeles-based Atiz Innovation Inc., which sells a variety of scanning rigs that allow library technicians to scan as many as 800 pages a minute. The final result is a digitally bound book made from images of the original.

Warnock said his business has doubled this year as more libraries and other organizations become aware of the value of scanning older documents.

The company says it has sold more than 2,000 of its scanning stations to libraries and government agencies around the world, including Stanford, UCLA and the Getty Center. The lowest-cost Atiz rig, called the BookDrive Mini, sells for around $6,000 without the pair of cameras. Canon models that go with it range from $500 to $7,000 each for high-end models

Hugh Bivens, a 79-year-old volunteer who worked for 40 years in a nuclear weapons lab, spends two days every week at the small Special Collections branch of Albuquerque’s public library system, scanning genealogy records on his Atiz scanner.

Last year, Bivens and his small team managed to scan in more than 350 volumes of birth, death and marriage records from New Mexico.

“We don’t have a lot of money to invest in this, so we do the best we can,” he said.

Libraries that can afford it are also springing for so-called robotic scanners — those that can automatically turn pages of bound books and scan them at high speeds. At the New York Public Library, technicians use a machine from Kirtas Technologies Inc. that keeps pages turning with small puffs of air, making it possible to record close to 40 pages a minute.

Kirtas sells its devices mostly to large research libraries and government agencies looking to digitize mountains of paper records — birth and death certificates, wills, deeds and other legal documents. Kirtas machines cost between $70,000 and $130,000.

Though it’s getting easier, digitization is still a time-consuming process, especially for manuscripts that must be scanned by hand. And because there is so much material — and so few scanners — it could take decades before a significant fraction of the world’s printed works are moved online.

Paul LeClerc, the New York Public Library’s chief executive, estimated that digitizing the library’s entire collection would cost “hundreds of millions of dollars,” while available funding is still a sliver of that.

Harvard has one of the largest digital scanning programs in the world and has undertaken a number of ambitious digitization projects. Over the next four years, the lab and its dozens of technicians, photographers and catalogers will digitize all 51,500 rare Chinese books housed in the Harvard-Yenching Library, likely the largest such collection outside of China.

In addition to its Chinese collection, Harvard’s digital laboratory is digitizing many of its medieval manuscripts and original musical scores and is adding images from its Virginia Woolf and Theodore Roosevelt collections.

“These folks have some of the most interesting jobs in the library world, because they touch the past, and they open it up to the future,” said Nancy Cline, the Roy E. Larsen Librarian of Harvard College.

With increasingly large tranches of once-restricted material available online, Cline said, the library is attracting interest from scholars far and wide.

“It’s brought a new democratization to research,” she said. “You don’t have to have thousands of dollars to travel here. You can start a lot of your discovery from wherever you are.”

ABOUT THIS SERIES

This is the fourth in a series of occasional reports exploring how technology is changing libraries, the publishing industry and the experience of reading. Previous installments, video reviews of e-book readers and e-book applications and a slideshow on the evolution of books are available at https://www.latimes.com/reading.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.