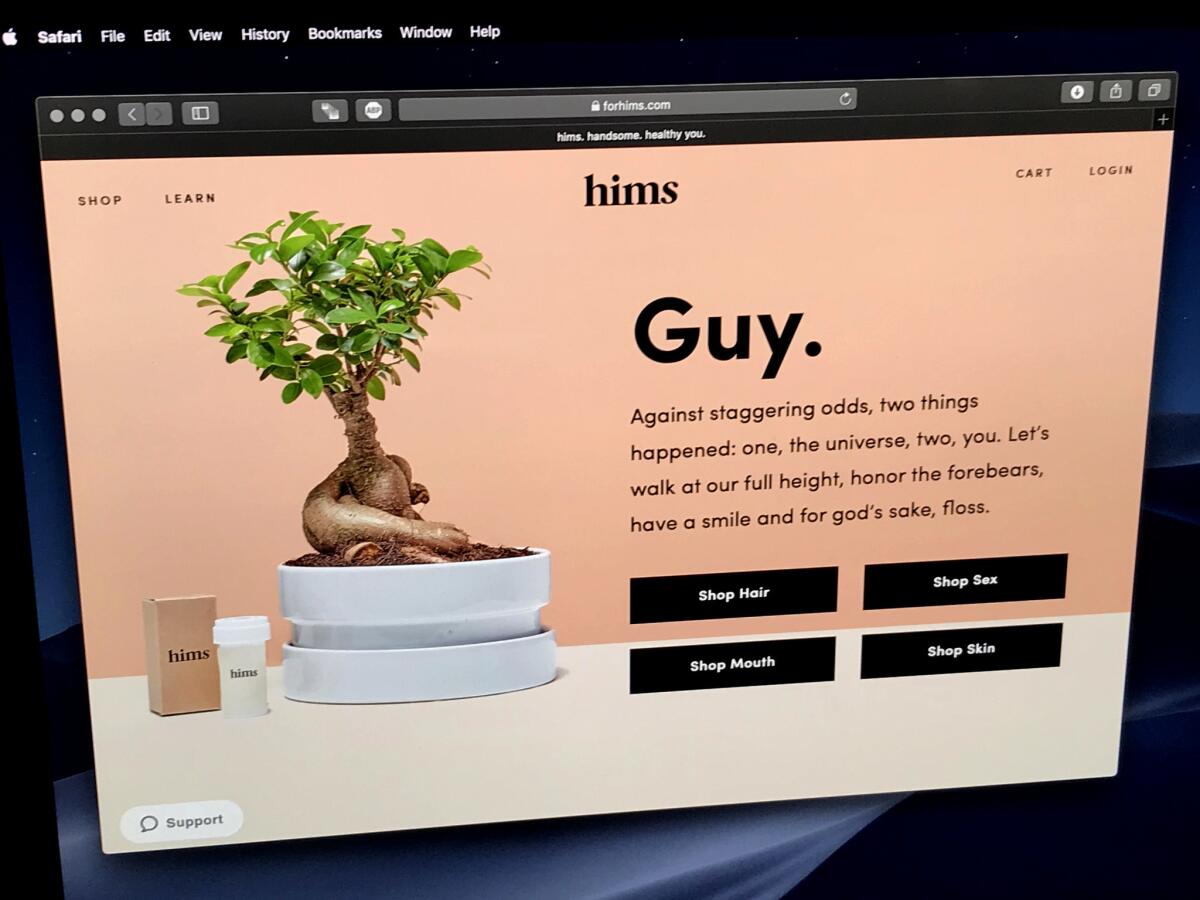

Young start-up Hims sells generic Viagra and Rogaine to the Instagram crowd

- Share via

Every man in Dylan Nelson’s family is bald. His dad, uncle and both grandfathers: all hairless. The 28-year-old headhunter from Newport Beach started suffering the same fate when he was 23. He tried Rogaine but found it pricey and ineffective. Then he saw a cheeky ad for Hims, a startup that sells mail-order kits of prescription drugs. Nelson asked his neighbor, a dermatologist, what she thought. The drugs Hims was offering were the same ones she prescribed to her patients but cheaper.

Two months in, they seem to be working. “I’ve been cutting my hair every 10 days,” Nelson said.

Hims is one of a crop of new direct-to-consumer, hipster-branded startups selling prescription drugs to men through the internet. But where others such as Keeps and Roman focus on one health issue (hair loss and erectile dysfunction, respectively), Hims wants to build a brand that serves men with many different ailments, including erectile dysfunction and acne. Launched in November, Hims makes it possible for men to get a prescription after a quick online consultation with a doctor. The meds are provided by a network of pharmacies and mailed out in clean, discreet boxes to avoid embarrassment or shame.

What makes Hims tick

Hims is riding a confluence of trends: the loosening of telemedicine laws in most states, the expiration of Pfizer’s Viagra monopoly and men’s growing willingness to talk about and pay for health and beauty.

Andrew Dudum, Hims’ 29-year-old founder and chief executive, vows to create a $10-billion-plus healthcare company.

“We’re the front door of the doctor’s office,” he said. “We are completely different from anything in the healthcare system.”

Dudum and his team of disrupters will have to tread carefully. After all, they aren’t selling mattresses or razors. They’re selling prescription drugs with potential side effects. And some experts say telemedicine, a global industry worth an estimated $19 billion that’s credited with bringing healthcare to underserved populations, could make it easier for people to get prescriptions that aren’t warranted.

Lindsey Slaby, a marketing consultant who has done work for Target Corp., Equinox and Microsoft Corp., applauds Hims for trying to make it easier for men to talk about hair loss, erectile dysfunction and other ailments.

But she said the company’s sometimes glib marketing could gloss over the downsides of pill popping.

“You just don’t feel like you’re seeing a lot of the fine print,” she said.

Dudum doesn’t have a medical background. He’s your archetypal San Francisco start-up guy: direct, optimistic and oozing good vibes. At the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School, he was in the venture capital club. He’s best known in tech circles for founding Atomic, a small venture firm that starts its own companies and is backed by Silicon Valley titans Peter Thiel and Marc Andreessen.

Dudum had been researching men’s health, looking for a way into the market, when one night over dinner his sister berated him about his nonexistent skin-care regimen. She grabbed his credit card and bought $300 worth of “French stuff” on the spot. The cost and the confusion over what exactly he was getting pushed Dudum to start Hims as a transparent, one-stop shop for men who don’t want to deal with late-night Google searches or sheepish trips to the store or doctor.

Hims has raised $97 million from investors like Institutional Venture Partners, Forerunner Ventures and Josh Kushner’s Thrive Capital. The latest round valued the company at $500 million, according to data firm PitchBook. Hims said it pulled in $1 million in revenue in its first week, a rate that has only grown since then. That’s at least $32 million in eight months, a pretty decent run rate for such a young startup. Dudum said signing up 2 million regular customers would generate almost $1 billion in recurring revenue.

Besides drugs for erectile dysfunction and hair growth, Hims sells skin-care products, a cold-sore remedy, scented candles, matches and a limited selection of apparel. (“It’s a sweater. It keeps you warm,” one product description reads.) The meds come in chic packaging, and the creams and shampoos lack the off-putting medicinal smell of your father’s foot ointment.

The key to Hims’ success so far is the availability of its two main drugs in generic form. At its peak, Viagra was a blockbuster for Pfizer Inc., with about $1.26 billion in U.S. sales in 2015.

Since cheap generics became available last year, the drug is barely a blip, selling less than $100 million in the United States in this year’s first quarter.

Merck & Co. Inc.’s hair-loss drug Propecia has followed a similar trajectory since debuting in 1997. In 2012, the year before going generic, Propecia sales reached $124 million in the United States. Two years later they’d dropped to $19 million.

A Hims prescription of finasteride, a version of Propecia, costs about $30 a month, less than what most pharmacies charge. For $44 a month, Hims bundles in medicated shampoo and minoxidil drops (minoxidil is the active ingredient in Rogaine), which sell for $30 over the counter at CVS.

The company is essentially building a brand around drugs that Pfizer and Merck spent years and hundreds of millions of dollars marketing. Targeting men in their 20s and 30s, Hims’ advertising leans sophomoric. Cheeky shots of drooping cacti and eggplants fill New York subway stations, urinals, podcasts, sports arenas (they’re plastered all over the bathrooms at San Francisco’s AT&T Park) and are on television during the NBA finals. They’re also all over Instagram, fitting right in with other direct-to-consumer ads for Casper mattresses and Harry’s razors.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration requires ads that make a specific claim about a drug’s benefit to disclose possible side effects. Hims said it’s selling a brand, not a specific drug, and doesn’t include the boilerplate language in its ads (which would clunk up the presentation). An FDA spokeswoman declined to comment on Hims ads.

Side effects

But some experts wonder if finasteride should be prescribed to healthy, young men. The drug was originally developed to help mostly older men shrink enlarged prostates. When it was also found to help regrow hair, finasteride was marketed to younger men (though older ones including President Trump take it, too). Recent studies suggest that finasteride can make some men have trouble ejaculating or maintaining an erection. A 2017 study found 1.4% of men got erectile dysfunction, some of whom had it for 3½ years or more after they stopped taking finasteride. Among younger men, those who took the drug for extended periods of time had a much higher risk of ED than those who didn’t.

Nelson Novick, a dermatology professor at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai New York, said that because hair loss isn’t life-threatening, it’s not worth the risk prescribing finasteride — especially to young men.

“It’s not some guy in his 60s, 70s and 80s where it may not make that much of a substantive difference,” he said. “Now you have young men who may end up with permanent dysfunction.”

While many doctors consider finasteride a safe and effective drug, Novick has stopped prescribing it.

The ease of getting a prescription through Hims also worries some experts. Patients fill out a health questionnaire that goes to one of a network of 124 doctors. Those suffering from hair loss take a few snapshots of their head. The physician might send a few follow-up questions by email, but there’s no need for a video or phone call. (Doctors are paid depending on the amount of time they spend seeing patients on the platform, regardless of whether they prescribe medication.)

The process is perfect for busy, potentially shy Hims customers, but without a real back-and-forth conversation with a patient, there’s the risk of missing important details. A 2016 study found physicians were less likely to order follow-up tests when working over the internet than when seeing patients in person. Telemedicine also gives people yet another excuse to skip regular checkups.

“You’re seeing a direct-to-consumer movement that probably will have some people doing things that are unsafe,” said Adams Dudley, director at the Center for Healthcare Value at UC San Francisco.

Hims said it has done the work to avoid the pitfalls of telemedicine. The ailments it focuses on don’t require follow-up exams. And the company said more than a third of Hims customers who apply for erectile dysfunction meds are rejected because they don’t meet doctor requirements.

“They’re trying to target these fairly universal problems and either help people who wouldn’t get care otherwise or make it easier for people to receive the care that they need,” said Arash Mostaghimi, a dermatology professor at Harvard-affiliated Brigham and Women’s Hospital who advises Hims. He argues that startups such as Hims will encourage men in their 20s and 30s who typically avoid doctors to plug into the healthcare system.

Hims, which has been live for nine months, has so far navigated the tricky space of direct-to-consumer medications. The company plans to keep rolling out new prescription drugs at a steady clip, expanding the breadth of what it offers as Dudum presses onward to his goal of becoming a household name in men’s health.

But each new drug will elicit new questions, and there are only so many medications that are safe and easy to buy online. Plus, even if Hims can nail online drug sales, it could potentially run into Amazon.com Inc., which this month signaled its intention to shake up the prescription medication market with the $1-billion acquisition of online pharmacy PillPack.

Dudum is adamant it can be done. “To build a brand for an entire gender, whether you’re 16 or 80,” he said. “That’s what we’re going after.”

De Vynck and Huet write for Bloomberg.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.