Charles Keating Jr. dies at 90; key figure in S&L collapse

- Share via

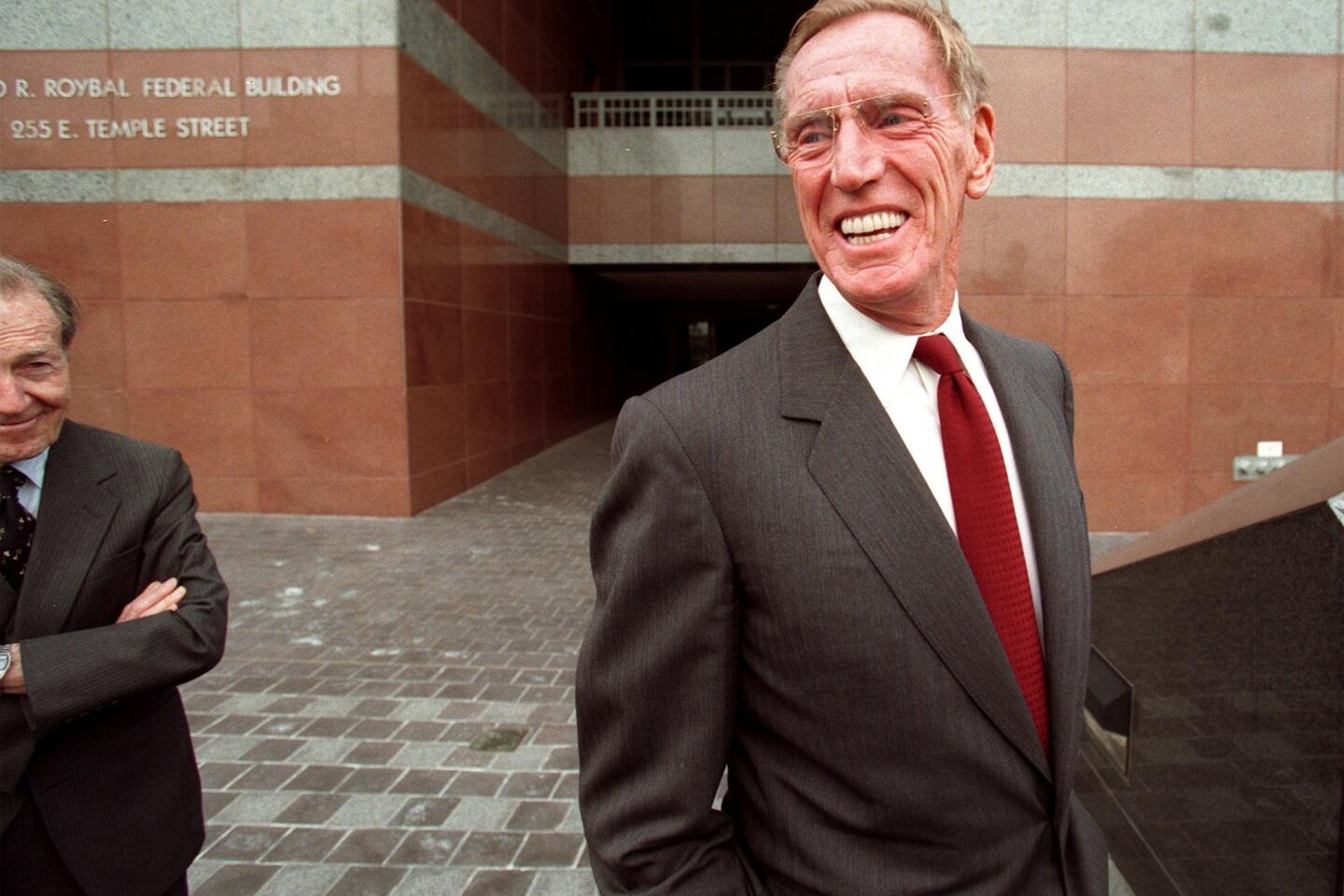

Willful and self-assured, Charles H. Keating Jr. strode through a life of outsized public roles — anti-pornography crusader, luxury hotel developer, political kingmaker — on his way to becoming one of the nation’s most notorious corporate rogues.

The harshest spotlight arrived in 1989 when regulators seized his Lincoln Savings & Loan after years of battles. The failure of the Irvine thrift, which had bankrolled Keating’s high-rolling investments, cost the government $3.1 billion, then the costliest bank collapse in U.S. history.

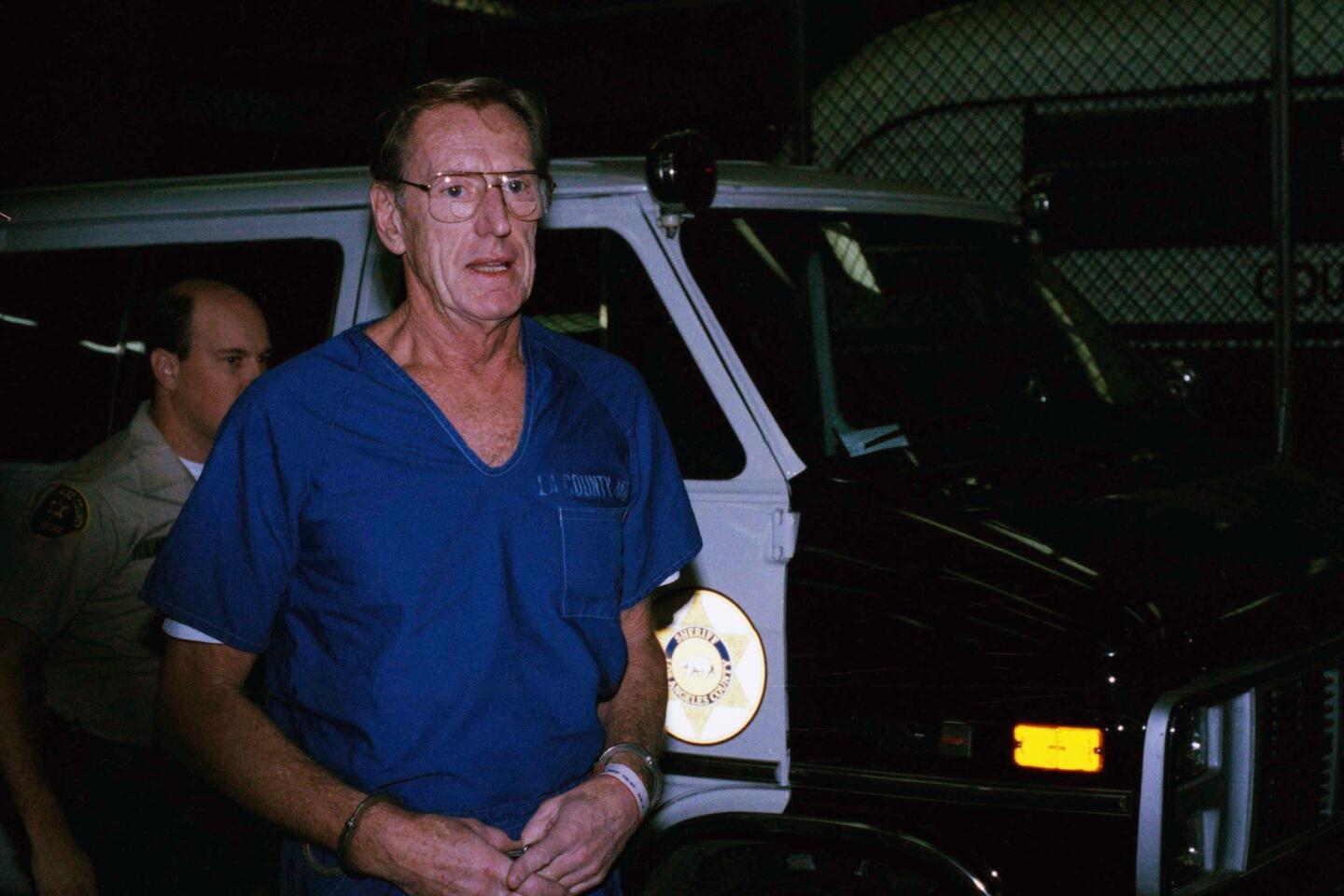

Keating became a national emblem of the fast-buck 1980s, and Lincoln became the poster child of the S&L crisis. In the early 1990s, state and federal juries in Los Angeles convicted Keating of looting Lincoln and swindling thousands of its customers — convictions that were later overturned. Many of them were elderly Southern Californians, who cashed out federally insured deposits to buy $265 million of uninsured American Continental junk bonds pushed by the S&L.

FOR THE RECORD:

Charles Keating: An obituary in the April 2 Section A of Charles Keating, the former operator of Lincoln Savings & Loan, misidentified his deceased daughter, Maureen Mulhern, as Maureen Hubbard. —

“He took their life savings and spent them on mansions, pleasure boats, private airports, indulgences of virtually every whim he and his family had,” Alice Hill, one of the federal prosecutors on the case, said at the time.

Keating, 90, died late Monday in a Phoenix hospital, according to his son-in-law, Bradley Boland, and a family friend. The cause of death was not released. He had moved to Phoenix in 1976 to run American Continental Corp., a land developer that bought Lincoln in 1984.

Before Lincoln blew up in scandal, Keating tarnished the reputations of five U.S. senators, including Arizona’s John McCain, who would later run for president. The “Keating Five” they were called, amid accusations that they interceded on Keating’s behalf to block an investigation by regulators.

In 1989, Keating addressed the intentions behind his massive political donations to the senators, delivering one of his trademark outrageous comments.

“One question, among many raised in recent weeks, had to do with whether my financial support in any way influenced several political figures to take up my cause,” he said. “I want to say in the most forceful way I can: I certainly hope so.”

Keating became a symbol for corporate malfeasance in the era of deregulation. In the 1980s, Congress and California’s Legislature lifted nearly all limits on investments by inflation-ravaged S&Ls. Billions of dollars poured from bank vaults into land development, corporate takeovers, foreign currency trading.

But no thrift operator rivaled Keating’s blend of arrogance, risk taking, political influence and multimillion-dollar payments to family and friends, said Michael Manning, a Phoenix attorney whom the government hired to spearhead a civil suit against Keating and his associates.

Deregulation “stoked Charlie’s coals and allowed him to fill Lincoln’s vault with federally insured cash,” Manning said. “He could gamble for those fast bucks with other people’s money.”

Under attack publicly, Keating once tried to burnish his image with a $500,000 radio campaign in Phoenix. Yet he had his share of supporters too, who saw him as passionate about his work, family and charitable causes.

A lifelong Roman Catholic, Keating donated $1 million to Mother Teresa through his corporation and whisked her around in a private plane when she visited the United States. Before his sentencing in L.A. County Superior Court, Mother Teresa was among 120 people who wrote letters pleading that Keating get probation.

“He was a deeply religious man. People often wonder if that was genuine, and it was,” said his lead defense lawyer, Stephen C. Neal, who spoke with him frequently. “He thought everything happened for a reason.”

Keating was born Dec. 4, 1923, to Charles Humphrey Keating, a dairy manager from Kentucky, and his wife, Adelle. He was raised in Cincinnati during the Depression. His father, who lost a leg in a hunting mishap, battled Parkinson’s disease in a wheelchair as Keating grew up with his younger brother William, who later became a congressman and newspaper publisher.

He graduated from St. Xavier High School in 1941. After struggling through a year at the University of Cincinnati, he joined the Navy, becoming a pilot with a reckless streak.

Stationed in the U.S. during World War II, Keating brought his Hellcat fighter in for a landing one evening in Vero Beach, Fla., his thoughts focused on a date and his radio blaring a Harry James trumpet solo. There was just one problem: He forgot to lower the landing gear. He had to leap from the plane as it skidded down the runway and crashed in flames.

“The tower was telling me, ‘Your wheels are up,’ but all I could hear was old Harry,” Keating told The Times in a 1988 interview.

Keating was on a fast track when he returned to the University of Cincinnati in 1945, receiving academic credit for his Navy service, earning undergraduate and law degrees in three years. A lifelong swimmer, he won the 200-yard breast stroke in the 1946 NCAA men’s championship.

That started a family tradition: His son and namesake, Charles Keating III; son-in-law, Gary Hall Sr.; and grandson, Gary Hall Jr. all competed as swimmers in the Olympics, where the senior Hall won three medals and the younger 10, including five gold medals.

Keating and his brother helped start a law firm that soon found itself with one major client: Carl Lindner, a wealthy Cincinnati financier. Keating ultimately went to work full time with Lindner, becoming a vice president and director at Lindner’s American Financial Corp.

A political conservative, Keating headed a drive to purge sexually explicit material from Cincinnati newsstands in the 1950s. His Citizens for Decent Literature grew to 300 chapters, and President Nixon appointed him to head an anti-pornography commission.

Keating’s prodigious political donations included a total of $1.3 million to the senators who became notorious as the Keating Five: McCain, California’s Alan Cranston, Ohio’s John Glenn, Arizona’s Dennis DeConcini and Michigan’s Donald W. Riegle Jr. All were Democrats except McCain, who had been especially close to Keating, visiting his Bahamas vacation compound at Cat Cay.

It was a measure of Keating’s influence that he persuaded all five senators to meet on his behalf with regulators who were conducting an unusually long audit of his S&L in 1987. Lincoln had been under investigation by the Federal Home Loan Bank Board, which subsequently took no action; the senators were accused of helping him improperly.

The Senate Ethics Committee found in 1991 that Cranston, DeConcini, and Riegle had substantially and improperly interfered with the probe, and Cranston received a formal reprimand. Glenn and McCain were cleared of acting improperly but criticized for “poor judgment.”

Like many S&L operators of the 1980s, Keating was a client of Michael Milken, the onetime junk bond king who wound up spending 22 months in federal prison for violations of securities laws. When Milken declined to provide further financing for Lincoln, Keating sold junk bonds directly to the elderly Lincoln investors — holdings rendered worthless when the savings and loan melted down.

Keating’s state court convictions for securities fraud, conspiracy and racketeering were eventually reversed after he served 4 1/2 years of a 10-year prison term. Jurors had convicted Keating on 17 counts of securities fraud. But the conviction was overturned by a federal judge who ruled that Superior Court Judge Lance Ito’s jury instructions had allowed Keating to be convicted without sufficient evidence that he intended to defraud investors.

His federal conviction was tossed out when it turned out the jury in that case improperly discussed his conviction in Ito’s court. He later pleaded guilty to federal bankruptcy fraud charges filed in Arizona, and was sentenced to time served.

Despite the overturned convictions, Keating’s reputation as the biggest villain of the S&L debacle’s endured.

“Charlie used his brilliance and charisma in all the wrong ways,” said lawyer Michael Manning, a fellow Arizonan who recouped most of the bondholder losses by suing law firms, accountants, investment banks and others that worked on Keating’s deals.

By the time Keating went on trial, he had an enormous family — many of them on his payroll. Keating had married Mary Elaine Fette in 1949. They had a son, five daughters and 24 grandchildren. One daughter, Maureen Hubbard, preceded him in death.

An audit showed that Keating family members had been paid $34 million in the three years before American Continental went bankrupt and Lincoln was seized.

They had three private planes and a helicopter at their disposal. Once, while planning the $300-million Phoenician Resort, Keating loaded more than 20 family members onto two corporate jets for a three-week jaunt in Europe. It was a business expense, he said, enabling the flock to research the finest hotels in France, Italy, Switzerland, Britain, Ireland and Germany.

Keating’s first trial, on state charges of securities fraud, took place in 1992. At the end of the trial’s first day, a 5-foot-tall elderly woman rushed to the front of the court. The tiny woman grabbed Keating by the lapels, screaming that Lincoln’s failure had cost her thousand of dollars.

“Mr. Keating, you took all my money away,” she yelled as bailiffs pulled her away from defendant. “What happened to my money? I can’t work anymore.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.