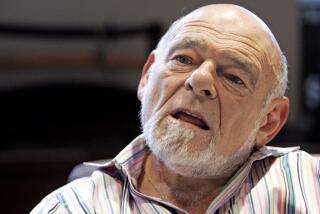

Remembering Sandy Sigoloff, corporate turnaround ace

- Share via

There was a time when Sandy Sigoloff could claim to be the most famous man in Southern California.

His face glared out from television screens in millions of homes every night, promising better bargains and sharper stores at the retail chain he was trying to rebuild out of bankruptcy. Business mavens and shoppers alike followed the daily progress of his rehab job on Wickes Cos., which sold furniture, hardware and groceries across the West and Midwest.

That was in the 1980s. Sigoloff, who died last week in Brentwood at the age of 80, is no longer widely remembered, partly because his conglomerate’s flagship chain, Wickes Furniture, finally gave up the ghost in a 2008 liquidation.

But our short memories do Sigoloff an injustice. The business he pioneered, the rescuing of companies that are deeply troubled but may not deserve to die, has become even more important in the U.S. economy since his heyday. Think General Motors, Citibank, Sears and Apple, among many others.

Not all have been restructured via bankruptcy like Wickes, but in most cases their turnarounds — some of which still are works in progress — use methods that were fresh when Sigoloff and a handful of other turnaround specialists, such as Victor Palmieri of Penn Central, first emerged. These include slicing away unprofitable locations, trimming the workforce and refocusing on the enterprise’s core businesses.

These may sound like self-evident principles, but the art of the turnaround was much rarer a quarter of a century ago. Sigoloff and a handful of others were among the first to take advantage of a 1978 bankruptcy-law change, which strengthened the ability of management to pursue its own reorganization plan under Chapter 11.

Today bankruptcy reorganizations and corporate restructurings have evolved into professional business disciplines. Sigoloff’s heirs have ranged from analytical investors like Ralph Whitworth to caricatures like “Chainsaw” Al Dunlap of Scott Paper and Sunbeam fame (or notoriety).

Sigoloff graduated from UCLA with physics and chemistry degrees and eventually became an executive at Xerox. He made his reputation as a turnaround ace at Republic Corp., which comprised the remains of the old RKO entertainment conglomerate, and then at Daylin, a Los Angeles-based retailer.

During this period he gave himself the nickname Ming the Merciless, drawn from the Flash Gordon comics he loved as a boy. It was a joke he later came to regret, for its suggestion of remorselessness didn’t match what friends and family members say was the pain he suffered laying off people, necessary as that might be to achieve a turnaround.

After his Daylin stint, Sigoloff wearied of the strain of nursing sick companies back to health and joined the home builder Kaufman & Broad as chief operating officer.

“No one was more organized than Sandy,” the firm’s co-founder Eli Broad told me last week. “He had a meticulous manner he’d gotten from his scientific and engineering training. But he wanted to run his own show.”

In 1982 the Wickes board called with the invitation for him to revive the $3.5-billion company. Starting in the 1970s Wickes had grown from a lumber retailer into a conglomerate, expanding haphazardly as though by repeated fits of absent-mindedness.

By 1981 the firm encompassed Wickes Furniture, the Builders Emporium hardware chain, a consumer credit company, a catalog merchant and supermarkets. The retail stores were dirty and in disrepair; on rainy days some of them had to place buckets around the sales floor. The financial accounting system was an impenetrable mess.

The company was loaded with debt and vulnerable to the recession that arrived in 1981.

Rescuing this enterprise would demand cunning, tenacity, a head for detail and a stupendous capacity for work, all of which Sigoloff brought to the table. He spent weeks carefully siphoning spare cash out of accounts at creditor banks and into a friendly institution, so he’d have operating capital the banks couldn’t touch before Wickes filed for bankruptcy, as it did in April 1982.

He drove his executives fiercely, holding daylong strategy sessions starting as early as 8 a.m. every Saturday. Most stuck with the job, a sign of the loyalty he inspired.

To assess the customer experience, Sigoloff made surprise visits to the stores. One day he surreptitiously traced his initials in the dust covering a mirror for sale at a Wickes Furniture location in West L.A. When the mark was still there a week later, he hauled over the store manager. He didn’t fire the man, but gave him what for.

“It became the most pristine store in the system,” recalls Los Angeles crisis PR executive Michael Sitrick, who was a Wickes corporate communications man when Sigoloff arrived.

Preventing mistrustful customers from fleeing because of the bankruptcy was a crucial challenge. Taking a page from Chrysler Chairman Lee Iacocca, whose self-confident mug was then appearing on TV pitching his cars, Sigoloff taped several commercials for Builders Emporium.

Playing off his “Ming the Merciless” persona, the spots opened with Sigoloff stating, “They call me the toughest retailer in America,” and ended with the tagline: “We got the message, Mr. Sigoloff!” Sales soared after the ads ran, Wickes said.

Wickes emerged from what was then the second-largest bankruptcy in history in 33 months. But more challenges lay ahead. Sigoloff had started rebuilding the company even before it emerged from Chapter 11, paying $1 billion for the consumer and industrial products division of Gulf & Western in 1985.

Sigoloff’s record of turning around troubled companies was impressive, his record of running them more equivocal. He had pledged to stay at Wickes at least 10 years, but in 1988 an unexpected decline in financial results, mostly from an ill-conceived acquisition of a textile firm, prompted him to cancel a planned management buyout of the company. The disaffected board then sold Wickes to the takeover firm Wasserstein Perella.

Sigoloff tried to rescue the parent of the high-end retailers B. Altman and Bonwit Teller, but that ended with the company’s effective liquidation, possibly because it was too far gone to survive.

In 1995, Gov. Pete Wilson nominated him as state superintendent of schools, but Sigoloff withdrew when fierce political opposition arose. Talk that he might be tapped as Orange County’s chief administrative officer during the county’s bankruptcy went nowhere.

Wickes was the high-water mark of Sigoloff’s career, but his legacy is greater. The idea that a corporation is more than the sum of its shareholders — that its factory communities, employees, suppliers and even the nation all have a stake in its survival — underlies the sometimes heroic efforts taken since then to keep businesses from extinction.

Sigoloff knew these efforts often required harsh actions — yes, merciless ones. He would know from reading his press notices that it’s hard for anyone who closes a factory or a store to be seen as an altruist. But with Wickes at least, he showed he wanted not just to rescue, but build.

Michael Hiltzik’s column appears Sundays and Wednesdays. Reach him at mhiltzik@latimes.com, read past columns at latimes.com/hiltzik, check out facebook.com/hiltzik and follow @latimeshiltzik on Twitter.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.