Setting a course for new technologies

- Share via

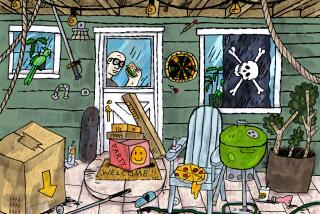

What is it about pirates that fascinates us so much?

It is not just the swords and swashbuckling (although I have three young sons who would disagree with that statement), since pirates have reappeared in so many guises over the years.

In the decades after World War II, the label was attached to rebellious disc jockeys broadcasting rock ‘n’ roll off the U.S. coast. At the dawn of the present century, it has been attributed to teenage nerds creating websites in their bedrooms to make free music downloads and software available to the masses.

Rodolphe Durand and Jean-Philippe Vergne find a common link among all these characters in their new book, “The Pirate Organization: Lessons From the Fringes of Capitalism,” published by Harvard Business Review Press.

These two academics — Durand is a university professor of strategy at HEC Paris and Vergne is an assistant professor of strategy at the Richard Ivey School of Business at Western University in London, Canada — see pirates as an essential part of any dynamic capitalist system.

Far from the lone discontents of popular myths, pirates form into complex and sophisticated organizations that both challenge and change the course of the markets in which they operate, Durand and Vergne argue.

Their book mixes historical anecdote and economic theory. It is aimed at people who think about industrial evolution, corporate strategy and the values of the market.

The authors are fascinated by pirates not so much for their actions of derring-do but the way they have driven capitalism’s adoption of new technologies. A crucial point they make is that the free market is never as free as those who create it may have us believe. “Capitalism is not liberalism,” the authors assert.

The reason pirates have cropped up repeatedly in modern history is that people are often unhappy at the way powerful nation states and monopolistic corporations frame the rules for new markets, be they ownership of the high seas, airwaves, DNA or the Web.

The authors define pirates as those that enter into conflict with states, especially when the state claims to be the sole source of sovereignty. These individuals operate in an organized manner in uncharted territory from a set of support bases outside that realm.

They also develop, as alternative communities, a series of discordant norms that they believe should be used to regulate the uncharted territory. As such, these pirates threaten the state by upsetting the very ideas of sovereignty and by contesting the activities of the corporations and monopolies the state has legitimized.

All this economic theory is paired with engaging analysis of the history and golden ages of piracy.

We are given a brief summary of the origins of piracy on the high seas, in which it is noted that many of those involved were more enlightened than the authorities they challenged.

Contrary to popular opinion, few pirate captains would have demanded separate quarters for themselves, usually bedding down alongside their crew. They were also highly likely to have women in their crews, the authors note.

The book also records the pirate tendencies of Apple co-founders Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs, who in the 1970s built a reputation as rebels on California campuses by selling a device that enabled students to make telephone calls without having to pay the monopoly at the time, AT&T.;

One group that the authors do not believe should be considered pirates are the bandits using assault rifles to terrorize container shipping lanes off of the coast of Africa. “Blackbeard … has far more in common with a cyber-pirate than with a Somalian peasant who uses a Kalashnikov to attack a fishing boat from a makeshift craft,” the authors note.

True pirates, it seems, are above such petty pilfering.

Moules is the enterprise correspondent of the Financial Times of London, in which this review first appeared. He is also the author of “The Rebel Entrepreneur,” published by Kogan Page.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.