A tycoon’s masquerade

- Share via

Few entrepreneurs have grasped as clearly as Richard Branson the importance of public relations in modern business.

Over the past 25 years, the tycoon has assembled an empire by trading access to the likable image that he and his Virgin brand project in return for hard assets and stakes in enterprises.

Behind the happy-go-lucky exterior is a carefully contrived pose. This portrays Branson — in fact a vastly rich, private-jet-toting tax exile — as a combination of hippie and buccaneer, a scrappy outsider taking on complacent and anticompetitive giants of big business.

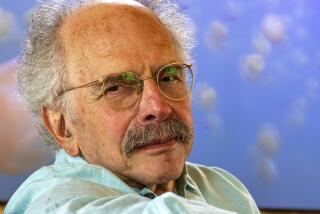

It is an image that Tom Bower, a stern and unbending investigative writer of the old school, has over the past decade and a half set out systematically to debunk. He took his first stab in 2000 with the publication of his Branson biography — a book described by its outraged subject as “a foul, foul piece of work from the first words to the last.”

Since then, Bower has twice honed his verdict. In 2008, he updated his opus. Now he has published a fresh volume.

As the title implies, “Branson: Behind the Mask” — published by Faber & Faber — continues the theme of probing the dissonance between public image and reality. But unlike its predecessors, it omits much of Branson’s business career to focus on recent events, such as his much-delayed attempt to launch a space tourism service.

Somehow, after years of peddling affordable fun to the masses, Branson has ended up betting the ranch — or at least several wings and the best pasture — on a venture offering four-minute suborbital flights to celebrities and jaded millionaires willing to part with $200,000 a go.

Branson’s capacity for reinvention is not new. It is matched only by his P.T. Barnum-like ability to generate excitement, generally through silly stunts, around the businesses he backs. The bigger question is why we, the public, go along with it.

It is not as if we cannot see behind the PR mask that obsesses Bower. What does it say about us that we still buy into the image, snapping up seats on Branson’s expensive and not very glamorous trains, or, even more puzzling, investing with Virgin Money (a venture Branson promises with almost comic chutzpah will deliver his objective of “a fairer distribution of wealth”)?

Bower never really explains. Much of the book is spent exploring Virgin’s financial performance, which he concludes is more rickety than its promoter would have us believe.

Stretched as it is across so many ventures, money is always scarce. Too many businesses fail or do not make money. Much of the cash flow has come from businesses that, far from being “challengers,” are established in highly regulated industries, such as the state-subsidy-guzzling railways.

One problem with Bower’s approach is that his thumb is always pressed rather too firmly on the scales. Branson is forever slightly in the wrong, whether for allowing initiatives to unravel, such as “The Project” — an ill-starred magazine app — or perfectly sensible commercial decisions, such as pulling out of a failing Formula One team.

Bower questions Branson’s business acumen, criticizing him for missing out on the Internet and the low-cost airline revolution. But if it were so poor, Virgin would be much smaller than it is.

And for a book that promises to take you behind Branson’s mask, you get little of the man himself.

The biggest problem about Bower’s pursuit is that he cannot ultimately run his quarry to ground. Branson now claims Virgin stands for something “beyond making money” and has started dismantling parts of the empire.

But the last chapter on Branson’s business career remains to be written. The master of self-reinvention could yet pull off another coup. I predict another book.

Jonathan Ford is the chief editorial writer for the Financial Times of London, in which this review first appeared.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.