Highland Park renters feel the squeeze of gentrification

- Share via

Vanny Arias isn’t sure how much longer she’ll be able to stay in the neighborhood where she’s lived all her life.

The last few years, she’s watched the changes sweep through Highland Park. “Newcomers” who spend $600,000 on a fully rehabbed Craftsman house. Trendy record stores and vintage boutiques have opened, along with restaurants that charge $10 for a hamburger with no fries.

And lately, she’s seen more friends move to South L.A., the Inland Empire, even Hesperia in the face of rent hikes and orders to vacate so landlords can remake the buildings for more affluent tenants.

That’s what happened to her mother, whose lease was terminated so the house on Fayette Street could be refurbished and sold. Now Arias shares a one-bedroom apartment with her mom and her three school-age children. Arias worries she could be next.

“How can I get up and move?” she said. “Where am I supposed to go?”

In the endless debate over gentrification in Los Angeles, Highland Park is ground zero. The hilly neighborhood northeast of downtown Los Angeles has become increasingly attractive to those who are being pushed east by escalating home prices and rents in places such as Hollywood, Silver Lake and Echo Park.

That’s prompted a wave of house-flipping, pushing home prices back to bubble-era highs. More recently, apartment buildings are increasingly being flipped, and that has many renters worried.

Nearly 30 apartment buildings in Highland Park’s 90042 Zip Code traded hands in 2014 — the most in a decade, according to real estate data firm Costar. Some of the buyers plan to keep existing tenants in place, though perhaps at higher rents, said Dana Coronado, a real estate broker who specializes in northeast L.A. apartment buildings. Others have bigger plans: empty and redo the building — often adding bedrooms and high-end finishes — to attract a wholly different class of renters at a much higher price.

“There’s a handful of buyers who are doing that. They have tons of money, and they’re willing to spend the hundreds of thousands of dollars it takes to redo these buildings,” she said. “They can’t get enough of them.”

Adaptive Realty, based in Westlake, spent $2.05 million in June to buy a 12-unit building on Avenue 55, according to property records. Today the building — next to the Gold Line light-rail tracks — is empty and surrounded by construction fence. City permits have been issued for a full rehab.

Adaptive President Moses Kagan declined to comment on the project, pointing instead to a recent blog post he wrote acknowledging that his company — which has remade dozens of apartment buildings across the eastern half of the city — has priced out some longtime residents. But those projects have helped improve the neighborhoods and bolstered the city’s tax base, he wrote.

“Nothing is permanent,” Kagan wrote. “Including where we live.”

A few blocks away on Avenue 57, construction fencing surrounds another empty building, this one bought in August for $2.45 million by PMI Properties. According to its website, the Beverly Hills-based firm focuses on “renovating obsolete properties into hip, ‘creative multi-family’ apartments that appeal to Gen Y, knowledge workers, creative class and urbanites.”

PMI partner Jeffrey Palmer said his company is sensitive to neighborhood concerns and is committed to Highland Park, where it owns a second building too. When the rehab is done, the apartments will be available to anyone, he said. Prices haven’t yet been set.

“Our goal as renovators is to create value for the people living there and businesses located there,” Palmer wrote in an email to The Times. “We sympathize with tenants who have been affected by our investment in the neighborhood and have tried to handle this process respectfully.”

That process, Palmer said, included voluntarily paying relocation benefits to prior tenants. Like many of Highland Park’s apartment buildings, the one PMI purchased was built after 1979, when the city’s rent stabilization ordinance went into effect. Unlike the nearly 80% of L.A. apartments covered by rent control, tenants there aren’t entitled to city-mandated relocation benefits — which can run as high as $19,000 per unit — and landlords can charge whatever the market will bear.

Some renters are turning to lawyers for help. More than 50 people showed up at a tenant-rights workshop held by the Eviction Defense Network in Highland Park last month, said Elena Popp, EDN’s executive director. But if a building’s not under rent control, there’s only so much an attorney can do.

“Ultimately, you lose this battle,” said Popp, who buys time for her tenants by dragging the process out in court. “Really, the only thing you can do is organize against it.”

That’s what some Highland Park residents are starting to do.

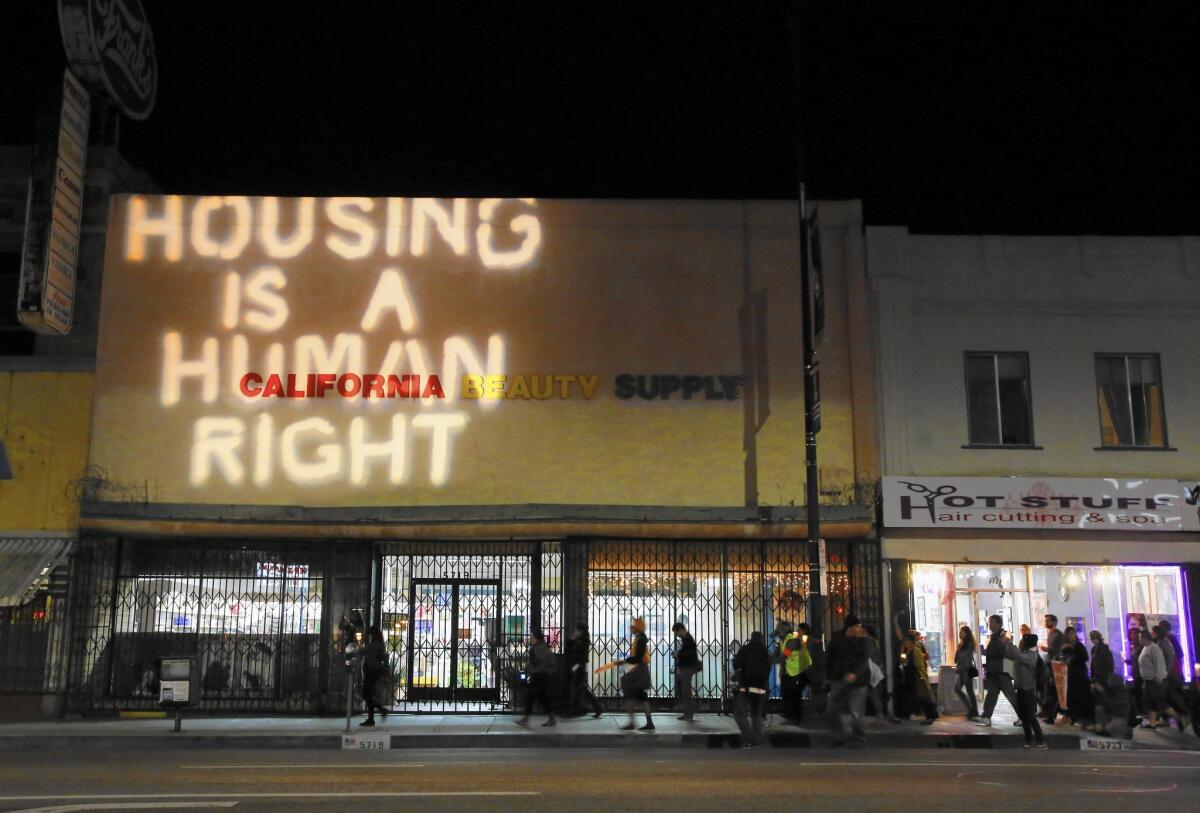

This month, about 100 people gathered in a park for a candlelight procession, a sort of vigil for a neighborhood that’s changing fast.

They marched down North Figueroa Street, handing out fliers to some of the new shop owners and waving signs at diners behind the window of a new French restaurant. They stopped in front of Adaptive and PMI’s two empty apartment buildings to share their “testimonios del barrio,” stories of what Highland Park’s changes have meant for them.

As a working single mother, Arias said she needed the support network that came with having roots in a neighborhood. A woman named Jordan, who declined to give her last name, said she welcomes the improvements — acknowledging that she frequents some of the “hipster” joints — but they’ve come at a cost to her community too.

“We do enjoy seeing parts of our neighborhood look nicer,” the 25-year resident of Highland Park said. “But behind those new and improved blocks is the residential blocks, where our family and friends don’t live any longer.”

Highland Park isn’t the first place this has happened, and it won’t be the last. Some speakers at Saturday night’s march came from Venice and Echo Park, where similar waves swept through years ago. Others came from El Sereno and Boyle Heights, and worried about the same thing happening there.

Organizers said they’d love to see stronger citywide protection for renters in these fast-changing neighborhoods, maybe even an expansion of rent control to cover newer buildings. But first, they’re trying to give renters — who make up more than half of Highland Park’s population — a voice in all the changes. “The whole thing is frustrating. We’re just not taken into account,” said Melissa Uribe. “The community that’s here is just being pushed out.”

This month, 10 would-be buyers inspected an apartment building up for sale near the 110 Freeway. It was listed at $2.2 million, with 13 units, no rent control and — as an ad put it — “HUGE Rental Upside!”

Teams of contractors and architects wandered around, checking out the pipes and passageways. In one empty unit, with a framed wedding picture on the wall and a stuffed Mickey Mouse on the couch, the men talked about knocking down a wall, opening up the kitchen and adding a second bedroom. A few days later, the building had received seven offers, Coronado said. A sale is set to close early next year, above list price.

Twitter: @bytimlogan

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.