Water created California and the West. Will drought finish them off?

- Share via

In what may become an iconic image for drought-stricken California, Gov. Gavin Newsom stood on the parched bed of Lake Mendocino on April 21 to announce an emergency declaration for Sonoma and Mendocino counties.

“I’m standing currently 40 feet underwater,” he said, “or should be standing 40 feet underwater, save for this rather historic moment.”

Newsom’s point was that the reservoir was at a historically low 43% of capacity, the harbinger of what could be a devastating drought cycle not only for the Northern California counties that fell within his drought declaration, but for most of the state — indeed, the American West.

Gentlemen, you are piling up a heritage of conflict and litigation over water rights, for there is not sufficient water to supply the land.

— John Wesley Powell, 1893

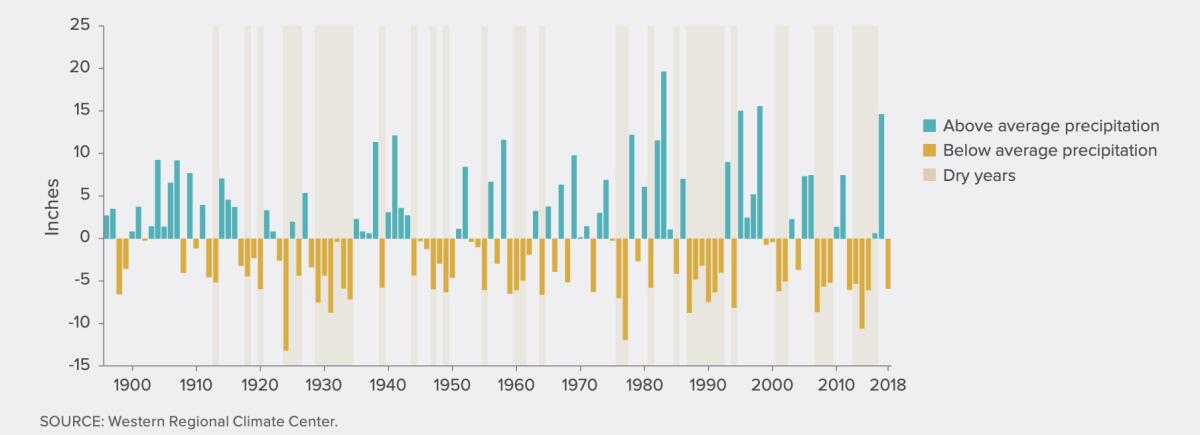

The last extended drought struck California in 2012-16. Still fresh in the memory, it was a period of stringent mandated cutbacks in water usage.

Lawns were forced to go brown, homeowners prompted to replace their thirsty yards with drought-resistant landscaping and to upgrade their vintage dishwashers and laundry machines with new water-efficient models. Profligate users were ferreted out from public records and, if they could be identified, shamed.

Although there have been wet years since then, notably 2017, the big picture suggests that the drought never really ended and the dry periods of this year and 2020 are representative of the new normal — a permanent drought.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Experts warn that climate change will only make things worse. The years 2014 and 2015 were the two hottest on record, “which made coping with water shortages even more difficult,” the Public Policy Institute of California observed in 2018.

Research suggests that extreme dry years will become more common, but so will extreme wet years. The latter isn’t a panacea for the drought, because the state’s water storage capacity can be overwhelmed by excessive rainfall, especially if a warmer climate reduces the snowpack, nature’s own seasonal reservoir.

Newsom’s step-wise approach of declaring emergencies in the hardest-hit regions of the state and holding back elsewhere until conditions spread shouldn’t leave any doubt that the crisis is just beginning.

“We’re definitely in a drought,” Jeffrey Kightlinger, general manager of the giant Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, told me. “This may go down as one of the five worst years on record.”

Despite what you may have gleaned from television and the movies, zombies aren’t always constituted of flesh and blood.

Water supply in the State Water Project, which distributes water to agencies and districts serving 27 million Californians and 750,000 acres of farmland, is so low that the project is delivering only 5% of requested supplies this year. The allocation has fallen that far only twice before since 1996, according to the state Department of Water Resources, which runs the project.

It may already be too late to avoid some of the conflicts and consequences of the drought age in California. Every segment of society will have to come to terms with deepening scarcity, and with each others’ competing demands.

Residential users, growers, the fishing industry and stewards of the environment will be increasingly at odds, unless the state can craft a drought response that spreads sacrifices in a way that each group considers fair. To ask the question whether that is likely is to answer it.

California’s water policies and infrastructure were products of an era of abundance. During a century of growth there always seemed to be enough water to satisfy demand — and when there wasn’t, engineering know-how and public funding provided the means to move water from where it was to where demand was growing.

That was the case with the construction of the Los Angeles and Colorado River aqueducts early in the last century and the State Water Project and federal Central Valley Project in succeeding decades.

Complacency marked some of this work. The expectations of the water supply that would be provided by Hoover Dam, for example, were based on surveys of the Colorado River’s flow taken during a historically wet period.

Heather Sears has been fishing for salmon out of this unassuming coastal community for nearly two decades.

The river has never provided as much water as was estimated in 1922, when the prospective supply was apportioned among the seven states of the Colorado basin. Dealing with the shortfall has been a challenge ever since, at one point even bringing Arizona and California to the brink of interstate war.

Water policy in California has historically been reactive rather than proactive. The first years of 2012-16 drought yielded the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act. Known as SGMA and signed by Gov. Jerry Brown in 2016, the law was the first to regulate the exploitation of groundwater, which feeds one-third of the state’s demand in normal years and half in dry years.

The SGMA places overdrawn groundwater regions, such as the southern part of the agriculturally rich Central Valley, under stringent rules starting in 2040.

Water levels at Lake Oroville have dropped to 42% of its 3,537,577 acre foot capacity.

The drought has already left its mark on California.

Rate increases by the San Diego County Water Authority averaging 8% a year over the last decade have driven many of that county’s avocado growers out of business, local farmers say, but the pain is more widespread: Agricultural acreage in the county fell to 234,477 in 2019 from 302,000 in 2010.

Residents in the San Jose region are facing annual rate increases for drinking water of up to 9.6% each year for the next eight years; that would mean increases of as much as $5.10 a month on their bills, according to the Santa Clara Valley Water District.

Let’s take a look at the implications for different segments of California society.

To begin with, the structure of California agriculture will have to change, though no one is yet sure how.

“The unfortunate reality is that some amount of farmland will probably have to go out of production to manage the reduced supply of water,” says Ann Hayden, a water expert at the Environmental Defense Fund in Sacramento. She calls for planning now “to support farmers as they’re making decisions about what lands to take out of production.” Fallowed land, she observes, creates air quality and water quality problems that will have to be addressed proactively.

The right-wing campaign to demonize the tiny delta smelt so Big Ag can get more water continues, ignorantly

Among the crops vulnerable to changing conditions are almonds, which at $6 billion in value are the state’s second-largest farm commodity (after milk and cream). Driven by the profits to be made, almond acreage has roughly doubled over the last decade to 1.6 million acres.

Almonds are known as thirsty crops, but the real significance of the expansion of acreage is that they’re permanent crops — they must be watered every year. As a result, almond orchards have been heavy users of groundwater. That’s a practice certain to come under pressure as the SGMA mandates come into effect in 2040.

Almond growers are only now starting to come to terms with the looming restrictions. “I’ve been in the industry for 25 years,” Holly A. King, a grower and chair of the California Almond Board, told the California Tree Nut Report last year. “What’s it going to look like in 25 more years? It’s not going to look like what it is today.”

As agricultural and residential demands take center stage, the environment suffers. In commercial terms, the fishing industry bears the brunt. The state’s salmon fishery was on the verge of being wiped out during the last drought stage. This one could finish the job.

As pressure intensifies on federal officials to increase releases from the Central Valley Project’s Shasta Lake — the reservoir behind Shasta Dam on the Sacramento River — to serve farmers, the threat to the fishing industry intensifies.

Water is complicated.

That’s because releasing water raises the temperature of the reservoir and then the river. “We’re looking at the loss of 90%-100% of juvenile salmon in the Sacramento River this fall,” says Barry Nelson, a consultant to the Golden Gate Salmon Assn. That would wipe out fall-run salmon, the industry’s lifeblood.

The last time that happened, in 2014-15, as few as 2% of naturally spawning fall-run salmon survived. “They were killed in their nests,” Nelson says. “They were cooked by high water temperatures.”

If there’s a bright spot in drought planning, it’s in the Southern California residential sector, which has become a world-leader in water conservation and recycling. Within the MWD, total water demand has fallen over the last decade even as the population has edged up to 19 million from 18 million.

Much of the gain has come from installation of stingier household appliances, but much more can be done in exterior demand through the planting of drought-resistant vegetation to replace lawns. “We think we’ve gotten all the low-hanging fruit indoors,” Kightlinger says, “but there’s a lot more we could do outdoors. We could probably squeeze out another 10% to 20% relatively painlessly.”

By pushing down demand, the MWD has been able to store more water. Its current storage of about 3.4 million acre-feet (one acre-foot or 326,000 gallons is enough to supply one or two families for a year) would cushion the district for about six or seven years, Kightlinger says, given expected supplies coming from the Colorado and in-state sources.

But more planning and management will be needed in coming decades. Some solutions that seemed drastic in the past are getting closer looks. Those include draining Lake Powell, north of the Grand Canyon on the Arizona-Utah border, and making Lake Mead, behind Hoover Dam, the primary reservoir on the Colorado River for California, Arizona and Nevada.

The “Fill Mead First” campaign says that would reduce losses from evaporation and preserve Mead’s capacity to generate hydroelectricity. But deliberately lowering Lake Powell would foster a political backlash in the upper-basin states of Wyoming, Utah and Colorado, which view Lake Powell‘s supply as a sort of guarantee that they can exploit the headwaters of the Colorado for their own purposes.

Both reservoirs are approaching critically low levels, with the surface of Mead currently about 150 feet below its maximum, with expectations that it could fall an additional 50 feet by late 2022; Powell is currently about 134 feet below its maximum elevation, and could fall an additional 25 feet by early next year, according to projections by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation.

If all this seems dizzyingly complicated, that’s the product of more than a century of fragmented water law and policy in California. The riddle can’t be solved by a patchwork of emergency declarations, no matter how urgent, but only by the crafting now of a comprehensive plan to address the inevitable consequences of climate change in the already arid West.

It’s well past time to come to terms with the words of John Wesley Powell, who led the first government expedition of the Grand Canyon, and who warned of a fraught future at a Los Angeles irrigation conference in 1893.

“Gentlemen,” he said, “you are piling up a heritage of conflict and litigation over water rights, for there is not sufficient water to supply the land.”

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.