Must Reads: Sean Parker built Napster and helped lead Facebook. Now he’ll guide you to the beach

- Share via

When a seaside property owner blocks beach access with a gate, the California Coastal Commission can order it removed.

When a developer builds along the coast without permission, the agency can rain down millions in fines.

But when tech billionaire Sean Parker chose a wedding venue in violation of the California Coastal Act, the state settled on a far more creative form of restitution: a mobile app.

Now after five years of collaboration between Parker — the founder of Napster and first president of Facebook — and the commission, YourCoast was unveiled Thursday at a commission meeting in Newport Beach and is available for download in the iOS app store.

The app marks an unusual convergence between two distinct California cultures: strict environmental regulators and rulebreaking tech types. It is also a rare high-profile coastal violation case resolved with cooperation rather than a legal fight.

The saga began in June 2013, just before Parker was set to wed artist Alexandra Lenas in a Big Sur redwood grove on a hotel property.

Workers had installed a 20-foot-tall gate, and set decorators had built bridges, a ruined stone castle and Roman columns in the old-growth forest glade. Crews installed a dance floor and a 50-foot stage for the band, and brought in fur-covered beds for guests including Gavin Newsom, Kamala Harris, Jack Dorsey and Sting to lounge on as the night wore on. The whole Tolkien-tinged event was on track to cost more than $4 million.

Then the commission crashed the party.

Download YourCoast in the iOS app store »

The site was supposed to be an affordable campground for the public that could not be closed for private events without permission from the commission. Upon investigation, officials found the owners had not only failed to get permission for the wedding — they had illegally closed the area to the public for six years.

Parker, like many Californians, had never heard of the agency. But with less than a week to go before his wedding, he sat down with the commission to hammer out a deal.

Violation of the Coastal Act can be expensive — the commission can determine an amount ranging from $1,000 to $15,000 per day for each day the violation persists.

Even though the property owner was at fault for the permit violations, Parker accepted the responsibilities. He covered $2.5 million in penalties, which helped fund hiking trails, field trips and other local efforts to increase public access to Big Sur. The wedding was allowed to proceed, since the commission determined that the construction and the party would cause no harm to the environment.

And in a first for the state, Parker agreed to help build an educational tool to benefit the citizens of California.

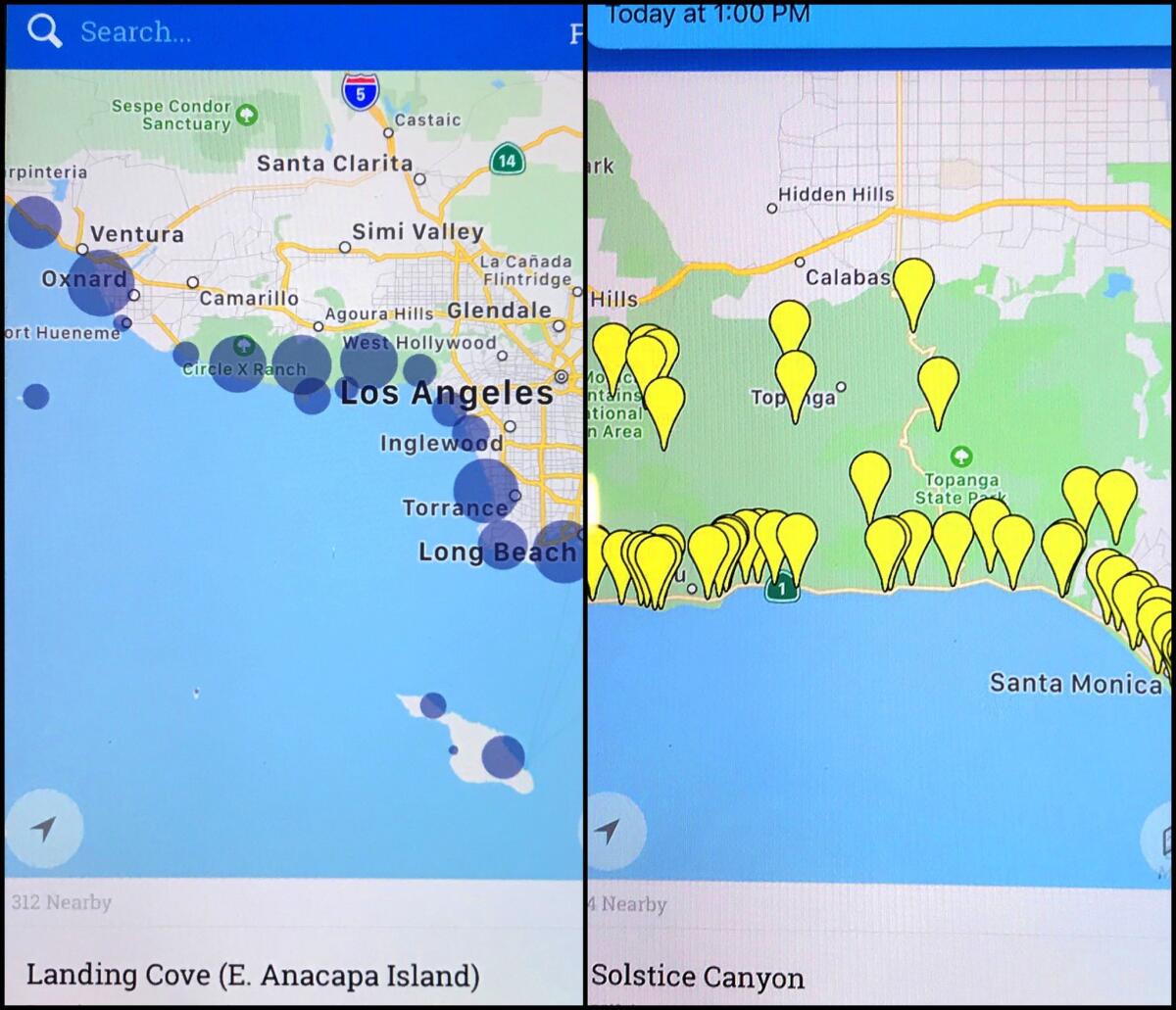

YourCoast shows users a map of 1,563 access points that the commission tracks along the California coast. Historically, this information has been available in California Coastal Access Guide books published every few years. In recent years it has also been available on the commission’s website.

Click on a particular access point and the app shows photos of the path to the beach — which can often be hard to find — and whether there are amenities such as parking, access for disabled visitors (with information on how to procure a beach wheelchair), restrooms or fishing facilities.

Users can also search for beaches with specific amenities and submit updated photos or report a violation to the commission. If visiting a remote stretch of coast, users can save the map and info on their phone for offline access.

Having a coastal access app had always been a pipe dream, officials said. They had a database, regularly updated by staff checking on the commission’s vast domain. But the technical requirements and costs had always been beyond what the commission could realistically request out of the state budget.

“We were spitballing ideas and mentioned an app,” said Aaron McLendon, the commission’s deputy chief of enforcement who met with Parker’s team. “As soon as we brought this idea up, it really caught on and he just kind of ran with it. … It was one of those great opportunities that turned a bad situation into a really good thing.”

Parker’s team noted that the app was built with sustainability and long-term maintenance at the top of mind. Citing a busy travel schedule, Parker answered a handful of questions via email and said that he was excited to work on the app because he “thought it would provide the greatest value to the public.”

The app marks as closed access points that are currently under dispute — and some remain unlisted. The commission is now tussling over access to 8.5 miles of coastline at Hollister Ranch in Santa Barbara County, and a number of access points in Malibu are notoriously contentious. Another tech billionaire, Vinod Khosla, has fought coastal officials for almost a decade over access to Martins Beach, a secluded stretch of sand south of Half Moon Bay. Hollister Ranch is not listed in the app; Martins Beach is marked “currently closed.”

Jennifer Savage, California policy manager for the Surfrider Foundation, said an app like this could empower more people to explore more of California’s coastline.

“There are so many places that aren't obvious, and that's a huge problem,” she said. “Having an app that just spells everything out is so reassuring, it makes you so much more confident that you’re in the right place.”

Often, public entry to the beach is just a narrow set of stairs or an alleyway next to a gated community — and certain neighborhoods are known for going out of their way to leave these entryways unmarked or unwelcoming.

Our Malibu Beaches, an app created a few years ago by an environment writer, had similar goals of guiding people past illegitimate “no parking” signs or orange cones slyly meant to block public parking spots.

Now with an app officially by the Coastal Commission, Savage said, “it reinforces that there are all these ways that you can get to the beach — and that you have a right to get to them.”

But it took the financial support and professional connections of Parker to bring that technological confidence to the people of California — and to bring the commission into the 21st century.

“Many of us are kind of older school,” said Al Wanger, who oversees information technology and records management for the commission.

The first time Parker’s development team met with the commission in 2013 to whiteboard app concepts, they were stunned to find that its headquarters in San Francisco didn’t (and still doesn’t) have Wi-Fi.

“Our former webmaster, a wonderful, talented young man who has since gone off to start his own company … he understood how to speak the language of the Parker folks,” Wanger said, “and could translate back to us about what was needed.”

The tech team was used to working in a venture-capital-backed world where the goal is to achieve massive growth or fail fast. The Coastal Commission — operating on a tight budget but devoted to an ambitious 1972 voter-initiated mission of regulating the state’s coast as a greater public good — needed a more sustainable model.

The final product is wholly owned, operated and maintained by the commission, which plans to keep the app running with current staffing. That means relying on data it was already collecting for its guidebook — organized in a spreadsheet and updated with each new coastal entry point that gets opened. The enforcement team, which has ranged from six to 10 people, has a backlog of thousands of cases.

They batted around the idea of letting users post photos and comments, but quickly realized filtering out unsavory content would overwhelm the office.

“We’re not Yelp, we’re not Google, where we have moderation staff,” Wanger said. “We do want people to get engaged and share things with us, though — we have an email box set up where we can look at submissions, and add to the photos and replace old photos where appropriate.”

Even making time for meetings with Parker’s team proved difficult for the staff, which had total control over design decisions like fonts, colors and layout. The developers sometimes wouldn’t hear back from the commission for months, and those delays begot more delays. Since the project began, iOS itself has gone through five major updates, each of which required rejiggering of the embryonic app’s code.

Read more: So many lovely beaches in Malibu, if only you could get to them »

The unique process makes it difficult to say how much the commission would have paid for similar services, but it estimates the value at around $300,000.

“We’re small, for our vast responsibilities of regulating all development over 1,200 miles of coastline,” McLendon said. “But we’re pretty scrappy, and I think that this outcome shows how we get creative to resolve things.”

The commission has worked out non-financial settlements in the past. One family that was operating an unpermitted horseback riding arena in Malibu agreed to hand over 22 acres of land near the Backbone trailhead to the Mountains Recreation and Conservation Authority, in lieu of a $1-million fine. Another set of violators in Santa Barbara donated 36 acres to county parks.

“These settlement agreements show we’re open to anything,” McLendon said. “So long as promoting coastal access and protecting resources on the coast is at the forefront, then the sky’s the limit.”

Parker’s not off the hook yet. His team is still standing by to help with the rollout, and has told the commission they’ll put them in touch with Android developers to adapt the app for the Google operating system.

He also owes the state one more thing: an educational video that is required to go viral.

Interested in more tech and coastal news? Follow @samaugustdean and @RosannaXia on Twitter.