California braces for deluge of child-sex-assault lawsuits under new law

- Share via

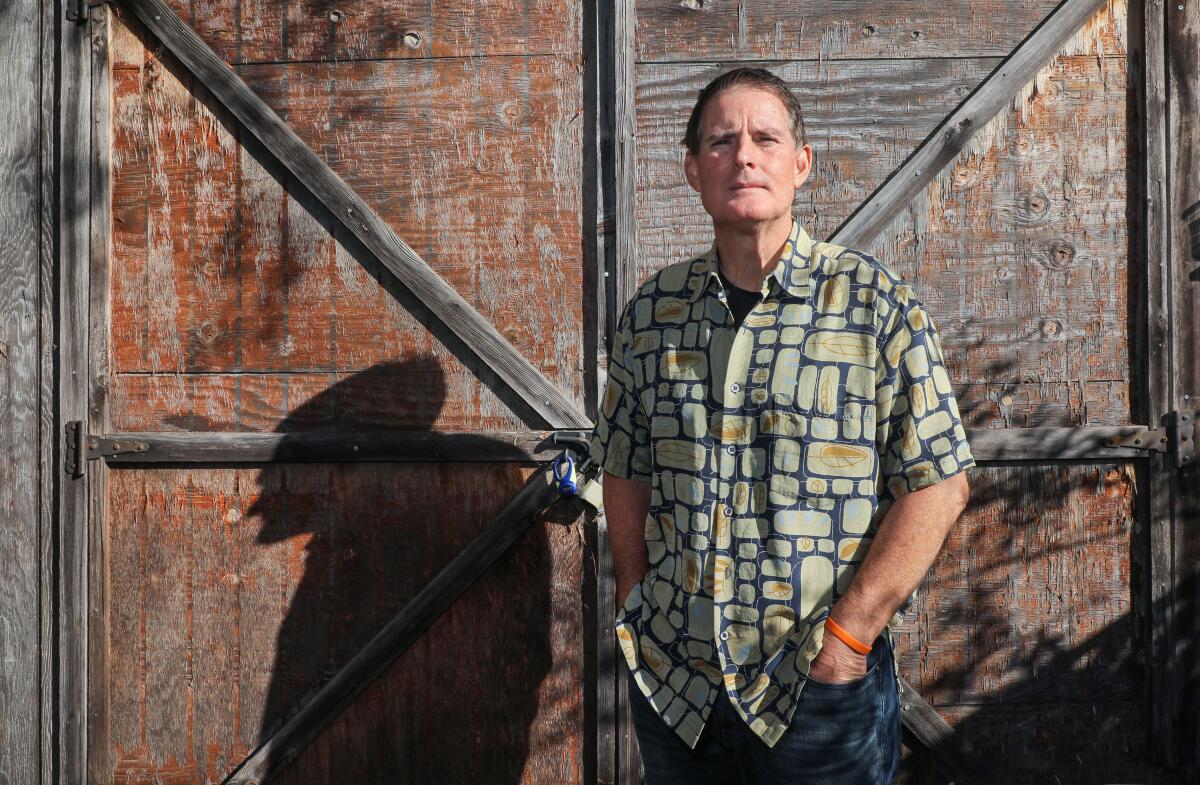

SAN DIEGO — Matt Smyth’s secret was revealed his senior year of high school with a knock on the front door of his family’s home in Fallbrook, Calif.

Two plainclothes sheriff’s detectives were investigating reports that Smyth’s former assistant scoutmaster — the one who’d driven kids to Boy Scout meetings, chaperoned camp-outs and hosted fishing outings on his bucolic property — had molested several boys.

To the shock of his parents, Smyth shared that he’d been a victim, too. But the bombshell stayed close to home for decades. Smyth never heard from the investigators again, and he moved on — or tried to.

More than 40 years later, Smyth is finally ready for his day in court and a public reckoning.

The 55-year-old, who still lives in Fallbrook, is among potentially thousands of Californians who are preparing to file sexual abuse lawsuits under a new state law that allows victims more time to report allegations of abuse and to take legal action.

Under existing law, victims of child sex abuse have until age 26 to file a lawsuit, or three years from the time of discovery that psychological injury was caused by sexual abuse suffered as a child.

The new law, which was sponsored by Assemblywoman Lorena Gonzalez (D-San Diego) and takes effect Jan. 1, raises the statute of limitations to 40 years of age, or up to five years after discovery. The law also opens a three-year window that allows victims of any age to sue on previously expired claims.

The new law, signed by Gov. Gavin Newsom last week, is expected to result in an avalanche of litigation aimed at indelible institutions such as the Roman Catholic Church and the Boy Scouts of America, as well as local school districts, foster care agencies, hospitals and youth sports organizations.

“We’re trying to make our clients whole,” said Andrew Van Arsdale, a San Diego attorney representing hundreds of former Boy Scouts, including Smyth. “There’s no amount of money you could pay these guys to make them go through what they went through again. This is at least a good-faith effort to do everything in our power to heal that wound, close that circle and get them the help they need.”

California joins New York and New Jersey, which passed similar laws this year, and other states such as Maine, Delaware and Utah, which have completely abolished civil statutes of limitations in these kinds of cases.

The cumulative effect is increasing the pressure on national organizations that are potentially facing a sustained onslaught of high-figure payouts, as well as prompting questions about how court systems can manage such a large volume of cases fairly and efficiently.

“The idea that someone who is assaulted as a child can actually run out of time to report that abuse is outrageous,” Gonzalez said in a statement after the bill was signed. “More and more, we’re hearing about people who were victims years ago but were not ready to come forward to tell their story until now.”

Gonzalez had tried to get a similar version of the law passed last year, but then-Gov. Jerry Brown vetoed it.

Brown, a former Jesuit seminarian, had called it a “matter of fundamental fairness.”

“There comes a time when an individual or organization should be secure in the reasonable expectation that past acts are indeed in the past and not subject to further lawsuits,” Brown wrote in a 2013 memo. “With the passage of time, evidence may be lost or disposed of, memories fade and witnesses move away or die.”

A similar one-year window had been allowed in California to file child abuse lawsuits in 2003, when most outrage was aimed at the Catholic Church over decades of abuse and cover-up. The flurry of litigation resulted in state dioceses paying a total of $1.2 billion in settlements.

The California Civil Liberties Advocacy and California School Boards Assn. were among those that opposed the latest bill.

The law places school districts around the state, particularly small or rural ones, in potential financial jeopardy, said Troy Flint, spokesman for the school boards association. “While we certainly believe in and support redress for victims of sexual misconduct, we want to ensure that we can provide a measure of compensation without imperiling our ability to educate today’s students and tomorrow’s students.”

He added that insurers have signaled the possibility of withdrawing from the state or declining to insure for these types of situations. “That puts schools in a very precarious state,” Flint said.

Auxiliary Bishop John Dolan said in a statement that the Roman Catholic Diocese of San Diego did not oppose Gonzalez’s bill, but it questioned the exception that protects state agencies from liability and sought “changes that would have made sure no victim was left out and that any person who was the victim of sexual abuse as a minor could have their day in court.”

The diocese, along with five others in the state, has given victims of Catholic abuse another option: to take a confidential settlement as part of the newly launched Victims Compensation Fund. If a settlement is accepted, the victim cannot sue.

Thousands of Californians appear to be lining up in anticipation of the chance to go to court.

“Our phones have been ringing pretty much off the hook,” said San Diego attorney Irwin Zalkin, who represents victims in sex abuse cases.

His firm already has about 150 to 200 cases that are being prepared to file over the next couple of years, he said. Most involve the Catholic Church and Jehovah’s Witnesses.

“It’s extremely meaningful for these survivors,” Zalkin said. “It’s cathartic for them to know they have the opportunity now to be heard, to seek some sort of vindication and have a voice.”

The law comes as claims of sexual abuse within the ranks of the Boy Scouts of America intensify.

Van Arsdale’s firm, AVA Law Group, has teamed up with two others — Eisenberg Rothweiler in Philadelphia and Tim Kosnoff in Houston — to create Abused in Scouting, a network that is focused specifically on allegations that the Boy Scouts of America has failed to protect generations of boys.

The alliance has just over 1,200 clients nationwide so far — about 300 of them in California, with 25 in San Diego County — many of whom see this as a men’s #MeToo moment. The team is building on prior litigation by others as well as investigative reporting by the Los Angeles Times that resulted in the 2012 release of the Boy Scouts’ so-called perversion files, a database of about 5,000 Scout leaders who’d been blacklisted because of reports of molestation from 1947 to 2005.

Of the new clients preparing to sue, Van Arsdale said, only 100 name alleged abusers who are in the public database. The rest — 1,100 — accuse previously unnamed suspects, with very little overlap.

“The numbers are overwhelmingly horrifying,” he said.

In a statement, the Boy Scouts of America acknowledged past abuse and apologized to victims.

“We are outraged that there have been times when individuals took advantage of our programs to abuse innocent children,” the statement read. “We believe victims, we support them, we pay for unlimited counseling by a provider of their choice, and we encourage them to come forward.”

The organization said it has taken significant steps over the years to prevent abuse and responded “aggressively” to suspected abuse, including mandated reporting to law enforcement.

“Safeguards like mandatory youth protection training, mandatory background checks, a ban on one-on-one interactions between adults and youth, mandatory law enforcement reporting, and a volunteer screening database are key parts of our multi-layered approach to help keep kids safe,” the organization said.

The Abused in Scouting attorneys have handed over about 1,000 redacted client case files to the Boy Scouts in recent months containing the names of accused leaders, troop designations and timelines.

“They’re in the process of going through that data and reporting that to local police,” Van Arsdale said.

Speculation that the Boy Scouts of America may file for bankruptcy protection as a way to compensate victims and still keep the organization alive has attorneys preparing for multiple options. The organization said it is still “exploring all options available” regarding potential financial restructuring.

Smyth said he doesn’t want to see the Boy Scouts go under. But he does want the organization held accountable for the harm he says it inflicted on him and others well into adulthood.

“I think they should come forward and be the organization they intended to be and could be and make right on all this,” he said.

It was in the mid-1970s when his troop got a new assistant scoutmaster.

“I’ll always remember him,” Smyth said. “At first he seemed like a good guy, he seemed to know a lot about the outdoors. Every time I’d see him driving around he’d be with kids, even outside of Scouting events.”

The Union-Tribune is not identifying the accused volunteer leader at this time because he has not yet been publicly named in a lawsuit.

The leader bunked with a group of boys in a tent during a camp-out one night.

“I woke up, he was basically inside my sleeping bag,” Smyth recalled. “He was fondling me, just all over me.”

Smyth said he told the man to stop, pulling the drawstrings tight on his new mummy bag, but the assault happened a few more times that night.

The same thing happened during another camping trip off the Colorado River in Yuma, Ariz., Smyth said.

The leader would sometimes invite the troop to a sprawling rural property with bass-filled lakes, Smyth said.

He remembered resisting the leader’s invitations to go into the big house but saw other boys go inside. Smyth said he soon lost his motivation for Scouting, fell into the wrong crowd and began abusing drugs.

The trauma resurfaced when the detectives showed up at his house a few years later, and again during counseling sessions and conversations with his wife over the years. He was watching TV recently when he saw a commercial for Abused in Scouting. He figured it was time to do something.

“They just haven’t followed proper procedures to protect people, and it sounds like they tried to bury this,” Smyth said of the Boy Scouts. Smyth said he never found out what happened to the troop leader.

But court records pick up the trail. The leader, who managed an avocado and citrus grove for his father, also volunteered as a Pop Warner football coach, according to records in San Diego County Superior Court. He was convicted of molestation charges and was believed to have abused the 14-year-old son of a family friend, a 7-year-old neighbor boy and at least three others, according to a mental health evaluation.

He was diagnosed as a mentally disordered sex offender in 1980 and sentenced to Patton State Hospital for nine years. The leader’s name does not show up in the previously released database of Scouting offenders.

Davis writes for the San Diego Union-Tribune.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.