When jail chaplains are volunteers, some faiths are more present than others

- Share via

There are days when Rabbi Avivah Erlick sits in her car outside Men’s Central Jail, too afraid to go in. She’s counseled hundreds of inmates, but sometimes she arrives downtown only to drive back home, not ready to face the sudden lockdowns, the stale air and the stories about violence and loneliness.

When she does go in, Erlick feels overwhelmingly behind. She used to be a part-time jail chaplain supported by a grant from the Jewish Federation, but it wasn’t renewed. Now she volunteers whenever she can. She spends hours updating her list of inmates to visit, which includes dozens more than she has time to see.

The work is too important to stay away.

“I listen — I’m the only person who does,” she said. “I went into chaplaincy because I feel so drawn to help people in crisis.”

The chaplains in the Los Angeles County jails, some of whom were once behind bars themselves, are united by a simple mission: remind inmates of their humanity. It’s a job they often do in one-on-one visits. They’ll tell jokes, share a prayer, teach a religious text, or simply listen.

Many inmates come from broken homes, have been homeless, or don’t have someone who cares about them. The attention and compassion of a chaplain can go a long way.

The county provides no funding for jail chaplains, so their presence depends on volunteers and religious institutions that may offer support. Consequently, chaplains from particular faiths can struggle or work long hours to meet the demand of inmates who want to see them.

Like Los Angeles, some of the state’s most populous counties, including San Diego and Orange County, don’t pay jail chaplains. But others, like San Bernardino, Riverside, Santa Clara and Fresno, may invest up to several hundred thousand dollars to have a few chaplains on staff. About 150 chaplains are paid to work in the state’s 35 prisons.

In the L.A. County jails, which contain approximately 17,600 inmates, Jewish and Muslim chaplains report a shortage of volunteers and institutional support from their communities, which affects the range of services they can provide. Several chaplains from Christian faiths, like the Protestant church, say that they have a sufficient number of volunteers.

“Certain communities are not as well-represented,” said Sheriff’s Sergeant Alex Gamboa, who works in the office of Religious and Volunteer Services for the L.A. County jails. “Eventually, somebody, your family or your friend, is going to come to jail and you’re going to want the support for them. … All these people everyone turns their back on are the ones that need the most help.”

Federal law protects the right of inmates to observe their faith. In certain cases, like if an inmate requests a chaplain from a minority faith, a jail might argue there’s no feasible way to provide that chaplain.

“The general rule is you got to accommodate prisoners’ religious practices unless you have a really powerful reason not to,” said Luke Goodrich, vice president of the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty, a nonprofit based in D.C.

Some aspects of religion and chaplaincy in jails are not tracked by officials. Gamboa said the county does not know the number of inmates by religious faith since prisoners are constantly entering and leaving custody. The county also does not keep a centralized count of the total number of inmate requests to meet chaplains, partly because inmates often make requests orally when they see chaplains in the halls.

While the jail has more than 1,000 chaplains and spiritual volunteers, officials have no effective way to independently monitor when they come in since many do so using a paper log-in system. About 20 people are listed as Jewish volunteers, Gamboa said, but he acknowledged many come in “every blue moon.”

Regardless, reports that the various faiths send to Gamboa’s office show a high demand for chaplaincy. The Archdiocese of Los Angeles, for example, has conducted more than 20,000 individual visits since January in both English and Spanish language counseling sessions.

The Muslim and Jewish chaplains will meet with people who show an interest in speaking to a chaplain from their faith.

“A lot of inmates may have information about Islam but they don’t practice or they don’t consider themselves Muslim,” said Maria Khani, a Muslim chaplain. “That’s between them and God. I have nothing to do with that.”

Gamboa said that while the jails always have chaplains available to meet with inmates, they don’t always have certain faiths on hand. For the most part, however, he said that the current system works and that his office asks chaplains to let them know if they are not able to meet with an inmate.

While it would be ideal for the county to fund full-time chaplains, Gamboa said, it’s a hard argument to make when some religions — like the Christian faiths — have dozens or hundreds of volunteers. Plus, he said inmates’ need for spiritual guidance seems limitless, so even having more chaplains might not satisfy the demand.

“Half our chaplains don’t talk about religion,” he said. “The inmates just want to talk about the pain and suffering they’ve gone through.”

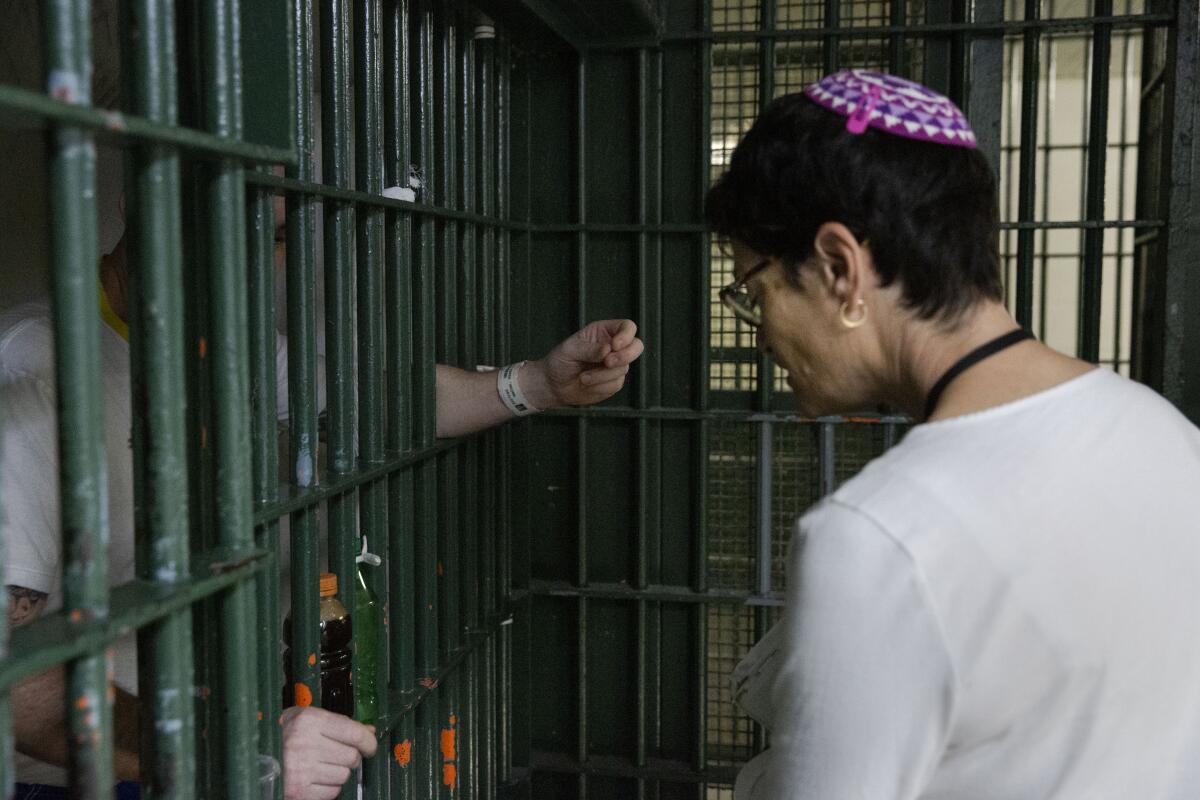

On one visit, Erlick spent the afternoon walking up and down broken escalators in Men’s Central Jail sporting a purple-patterned kippah. She made her way in and out of narrow cell rows where TVs blared and inmates called out to her from under bright florescent lights.

Jail staff pulled inmates out of their cells so that she could talk to them in the hall — discussions that lasted anywhere from two to 20 minutes. With a smile, she often started by gently asking how they were and if they wanted to talk, later offering them a prayer book with Reform, Conservative and Orthodox Jewish adaptations that she had proudly made herself.

During one stop, Erlick sat on a metal bench with two inmates from the gay and transgender unit. One said she had just had surgery and Erlick offered to recite the mi sheberach, a prayer for healing.

“Mi sheberach avoteinu: Avraham, Yitzhak, v’Yaakov, Sarah, Rivka, Rachel v’Leah…” Erlick began, while the inmate bowed her head, listening.

Another inmate, who said he was a Jew from Iran, asked if Erlick could bring him tefillin, a ritual object worn around one’s arm during prayer. He explained that he had been wrapping his arm with toilet paper.

“It keeps me in my place, with my people,” he said.

The inmate told Erlick that their sessions make a difference.

“It really means a lot to me that the religious leader of my belief wants to visit me,” he said.

To rise above the loneliness of everyday life, many inmates seek out spirituality any way they can. As Erlick sat with an inmate in the hall outside his cell, he told her that all he tries to do is read and stay out of people’s way since trouble can erupt at any time. The inmate, who is Jewish, said he attends Christian classes as an escape.

“You do anything to get out,” he said. “It feels very secluded and isolated in there. Anything that inspires learning, wisdom.”

Keeping up with requests became much more difficult, Erlick said, after the Jewish Federation decided not to renew an approximately $40,000 yearly grant. In 2016 and 2017, it had funded 50 hours of work a month for two chaplains to visit three facilities.

Now, Erlick said, “I’m so massively behind you can’t even call it behind.” Erlick only regularly follows up with a couple of inmates when she’s at the jails, but when she updated her list of inmates at Men’s Central in October, she had 46 people to visit. She does not know whether other volunteers are visiting the same inmates.

Rabbi Yankee Raichik, who receives a monthly stipend from the Aleph Institute, an Orthodox Jewish organization, to work as a jail chaplain, agreed that “there’s always a backlog.”

“It’s a terrible shame,” said Joel Kushner, who had applied for the grant as the director of the Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion’s Kalsman Institute on Judaism and Health and said the Federation had told him it had competing priorities. The Federation did not respond to requests for comment.

The Muslim community has seen similar challenges with obtaining outside support. Khani, the Muslim chaplain who since 2008 has driven from her home in Orange County to volunteer in the Los Angeles jails, said recruiting volunteers is difficult.

Khani works with several other volunteers who provide services at the county jails on a weekly basis, including a Friday prayer service. She’s always rushing to see inmates within a week or so of their requests.

“I’m not super woman,” she said. “I love my job. I love it so much, but I need help. And we don’t have dedicated people to do that yet.”

On a recent visit to Twin Towers Correctional Facility, Khani started her rounds shortly before dawn. She wore a black hijab and pushed a cart with religious materials to hand out. As she walked, some inmates called out “Salaam Alaikum.”

She met with an inmate who pulled a Quran out of a yellow bag attached to his wheelchair. He began telling her that lately there had been a lot of turmoil in the jail, so she encouraged him to read the Quran.

“It gives you a sense of peace so you will not be overwhelmed by things happening around you,” she said, before handing him a set of white prayer beads.

Muslim inmates have filed complaints about their ability to practice their faith. A complaint filed by three inmates last August against the sheriff’s department alleged that the jail had prevented inmates from participating in the Friday Jumu’ah prayers. After being provided with a copy of the complaint by The Times, the Sheriff’s Department said that it had not yet been officially served the lawsuit and was unaware of its contents.

Patricia Shnell, an attorney from the L.A. chapter of the Council on American-Islamic Relations, which filed the lawsuit, said that beyond the litigation, CAIR has been working to recruit volunteers by trying to have the topic raised at sermons in mosques. But she asserted that the small number of volunteers doesn’t excuse the jail from its responsibility to accommodate.

“Even if there is a lack of Muslim volunteers, they still have an obligation to allow people to practice their religions freely,” she said, holding that jail staff, for example, could allow inmates to lead their own services.

Some of the Christian faiths have much larger pools of volunteers. Frank Mastrolonardo, a protestant chaplain and founder of a nonprofit prison ministry, oversees more than 600 volunteers. He said most come in multiple times a week and that there’s no need to actively recruit.

The Catholic Church’s archdiocese funds six full-time chaplains and has about 100 regular volunteers who come in regularly, according to Gonzalo De Vivero, director of its Office of Restorative Justice. Thousands participate in the church’s communion services and masses, as well as its jail-based rehabilitation program.

But he aspires to do more. One of his dreams, he said, is to create a reentry program where parishes would adopt an inmate every year or six months to help them do things like rent an apartment and find a job.

“They are paying the price, they are paying the consequences, but that doesn’t mean we have to label them as dangerous, unwanted and unreachable,” he said. “They are regular people that can turn around.”

Some religious volunteers’ compassion for inmates comes from their own experience with incarceration. Michael Cherry, who has worked in the L.A. County jails for more than seven years as an evangelical volunteer, found religion when he was an inmate about three decades ago. A chaplain had offered him some biblical scriptures to read, and Cherry was moved by passages that touched on forgiveness and accountability. One from Corinthians read, “When I was a child, I spoke as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child; but when I became a man, I put away childish things.”

“I would have to grow up, it was time to man up,” Cherry recalled thinking.

Jesus Lopez was one of the inmates that Cherry counseled years later. Lopez, who lives in Los Angeles, was discharged from Men’s Central in 2018 after more than three years in the jail. He attended Cherry’s weekly Bible sessions and credits chaplains like him with giving him hope that he could live a better life.

“Hope of somebody caring, somebody loving,” he said. “There’s a lot of people that don’t have that, and to be given that of all cases in there ... it’s a beautiful thing.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.