Irene Hirano Inouye, champion of Japanese American causes, dies at 71

- Share via

Irene Hirano Inouye, a prodigious fundraiser who led the nation’s premier Japanese American museum in Los Angeles and built bridges across cultures with groundbreaking projects, has died. She was 71.

Inouye was diagnosed last year with leiomyosarcoma, a rare form of cancer, and died April 7 at her Los Angeles home, said her daughter, Jennifer Hirano.

The Japanese American leader, whose soft-spoken mien belied powerful drive and farsighted vision, rose to national prominence in the nonprofit world as board chair of the Ford and Kresge foundations. A major achievement was her “shuttle diplomacy” between the two foundations, which resulted in their combined gifts of $225 million to jump-start the successful 2014 effort to bring Detroit out of the nation’s largest-ever municipal bankruptcy, according to a statement by Kresge Foundation President and Chief Executive Rip Rapson and Board Chair Elaine Rosen.

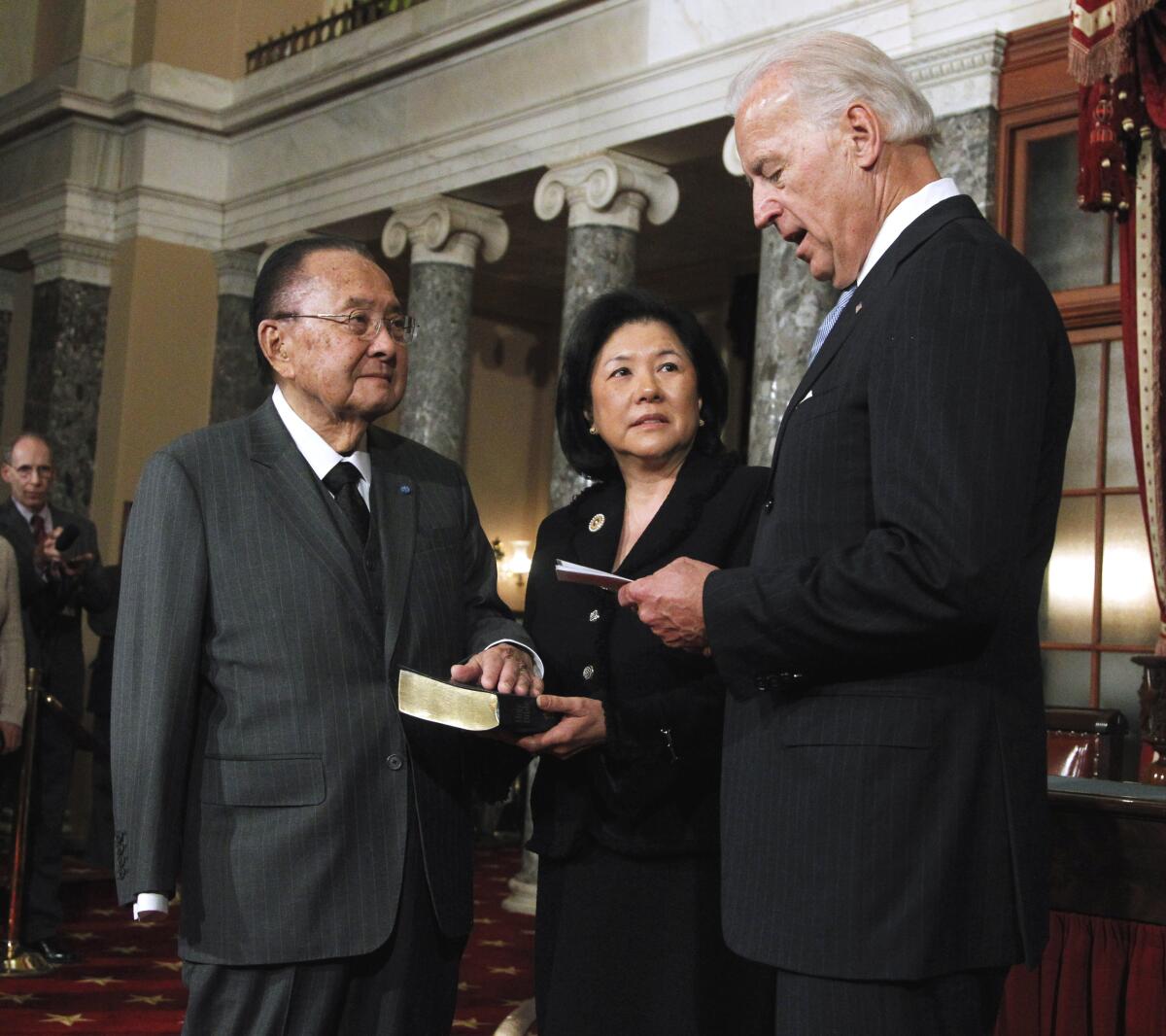

But in California and across Asian America, Inouye is best known for her work over five decades to empower women of color, develop the Japanese American National Museum and launch an international council to deepen ties between the United States and Japan. She was the widow of the late U.S. Sen. Daniel K. Inouye, the powerful Hawaii Democrat who died in 2012.

“Irene was a visionary and she was golden in everything she touched,” said Mitchell T. Maki, president of the Go For Broke National Education Center, which preserves and shares the history of Japanese American veterans of World War II.

Irene Ann Yasutake was born Oct. 7, 1948, in Los Angeles, the oldest of Jean and Michael Yasutake’s four children. Her mother was a homemaker and her father a U.S. Army major who served in the military intelligence service as a translator during World War II and later became an international businessman.

After graduating from USC with bachelor’s and master’s degrees in public administration, she worked as executive director for T.H.E. Clinic, a South Los Angeles health clinic that primarily served women of color. Through her community work, she met Los Angeles County Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas, who was then a high school teacher, and forged a lifelong friendship.

At his invitation, she joined the local Los Angeles board of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and, Ridley-Thomas said, worked hard to spread the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s founding vision of social change through nonviolent resistance.

“She was always there,” Ridley-Thomas said. “She was warm, unassuming, loyal, faithful, diligent. I just wish there were more people like her in the world.”

In 1976, she caught the attention of then-Gov. Jerry Brown, who appointed her to head the California Commission on the Status of Women. She advocated gender pay equity and called out efforts by male state legislators to defund the commission as “an insult to every woman in California.”

In 1980, she helped form local and national networks to empower Asian Pacific American women, whom she believed lacked visibility and leadership opportunities. She fought against the abuse of Asian women brought to the United States as mail-order brides and sought greater representation in educational, employment and political realms.

“Many of us are conditioned to sit back, get done what needs to be done and not confront,” she told The Times in 1980. “It’s much easier that way, but we must fight against falling into that trap.”

Her defining work came after businessman Bruce T. Kaji and a group of World War II military veterans joined forces in 1985 to launch what was then an audacious idea: a national museum to honor the history and culture of Japanese Americans. Inouye was hired over 150 applicants in 1988, according to a museum history.

Actor George Takei, who has served on the museum board since its inception, said Inouye brought an “indefatigable” work ethic, “calm competence” and extensive management and fundraising expertise.

She traveled the nation and later Japan with prominent Japanese American business leaders as they enlisted community support and collectively raised more than $60 million for the museum. A breakthrough donation was $10 million from the Keidanren, Japan’s leading economic and business organization, reflecting the group’s work to bridge divides between Japanese Americans and their ancestral country rooted in World War II.

Inouye oversaw three major expansions of the museum, whose primary holdings are housed in a state-of-the-art pavilion in Little Tokyo. The museum explored the World War II incarceration of 120,000 people of Japanese descent in an exhibit provocatively titled “America’s Concentration Camps,” the history-making heroics of Japanese American soldiers, the art of Isamu Noguchi, untold stories of first-generation Issei pioneers. The museum became an affiliate of the Smithsonian Institution, giving it access to artifacts, traveling exhibits and collaborations.

“Irene was always looking forward: ‘What’s the next big idea?’” said Chris Komai, a former museum official who worked with her for 18 years.

Former congressman Norman Mineta said one of Inouye’s greatest legacies is her bridge-building to Japan and to other communities.

After the Sept. 11 attacks, she arranged a meeting between museum board members and leaders in the Arab, South Asian and Muslim communities in Michigan. Ultimately, the Japanese Americans offered support to launch an Arab American National Museum and have led efforts to use their wartime incarceration as a warning against scapegoating Muslims, immigrants and other vulnerable groups.

‘Without her, we wouldn’t have become the Japanese American National Museum that we are today.’

— George Takei

“Without her, we wouldn’t have become the Japanese American National Museum that we are today,” Takei said.

But her vision and ambition could be costly, as she took exhibits to Brazil, Hawaii and Japan. Fundraising for the expansive pavilion fell short. The museum fell into a $10-million debt, leading to pay cuts and layoffs.

Inouye also got caught in a tussle over the museum’s direction. Her growing interest in building ties with Japan was opposed by some board members who believed the focus should remain on the Japanese American experience.

In 2008, she announced she would marry the senator and resigned from the museum. (The museum today has reduced its debt to $2.37 million and held membership steady at about 20,000, according to current President Ann Burroughs.)

Inouye pursued her passion to strengthen trans-Pacific ties by helping launch the U.S.-Japan Council in 2009 and served as president until resigning in January. The council has promoted exchanges between Japanese American leaders and counterparts in Japan, including those affected by the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami.

Despite Inouye’s many awards and leadership roles in the educational, cultural and nonprofit worlds, Jennifer Hirano said her mother rarely talked about herself and never lost her humility.

“She had a bit of the Japanese American spirit: You keep your head down, you do the best work you can, but you don’t necessarily talk a lot about it,” Hirano said.

In addition to Hirano, Inouye is survived by her mother, Jean Yasutake, sisters Linda Hayashi and Patti Yasutake, brother Steven Yasutake, stepson Kenny Inouye and granddaughter Maggie Inouye.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.