Cesar Chavez’s grandson wants to introduce his ‘Tata’ to a new generation

- Share via

KEENE, Calif. — When I visited the National Chavez Center earlier this summer, the solemnity of the site hit me the moment I parked.

It sits on 187 gorgeous acres in the foothills of the Tehachapi Mountains, at the end of a winding forest road. All around are old buildings — houses, barns, trailers — that are what’s left of La Paz, the kibbutz-like community Cesar Chavez established in the 1970s and where his final resting place is.

Waiting to greet me at the entrance was Andres Chavez, the center’s executive director.

Andres is also Cesar’s grandson.

“See these steps right here?” he said as we began our tour. He gestured to the path up to the gravesite of his grandparents, surrounded by rose bushes in front of a fountain with five spouts to remember the people killed while protesting at United Farm Workers actions. “I used to skateboard here before school.”

What many consider sacred grounds Andres also knows as his childhood home.

For the record:

7:35 a.m. Aug. 24, 2022A previous version of this article described Cesar E. Chavez’s home at the National Chavez Center as having two stories. It has two bedrooms.

The two-bedroom house where Cesar and Helen lived? Andres remembered “stacked” Christmas Eve parties where Helen gave out socks to her grandchildren as presents. A playground behind a chain-link fence? Andres and his friends used to ride their mountain bikes down the slides. The soup kitchen that Andres plans to reopen to host visitors? He cleaned dishes and swept floors there as a kid during community meals and got paid in cheeseburgers.

We passed by the refurbished headquarters of the United Farm Workers and the Cesar Chavez Foundation, the two organizations through which the labor leader launched his people-power revolution. We went into the visitor center, which offers a short documentary about the history of the place, photos from el movimiento, a replica farmworker shack, and Chavez’s office the way he left it at the time of his death in 1993, down to brimming bookcases and a notepad with a to-do list.

Andres pressed a button to launch a short narrated program complete with spotlights on different parts of the office.

Nothing happened.

“Huh,” said a sheepish Martha Crusius. “It wouldn’t stop playing, and now it won’t play at all.”

Crusius is the National Park Service program manager who helped prepare the documentation to establish the César E. Chávez National Monument, dedicated in 2012 by President Obama and consisting of the graves of Cesar and Helen Chavez, as well as the visitor center.

Andres smiled. “We’ve got work to do here.”

He’s been in charge of the National Chavez Center since April, but had already made a name for himself in the Central Valley beyond his pedigree. He helped start one of the few political radio shows in California hosted by Latinos and helped with COVID-19 vaccine rollouts throughout Kern County. Right now, he’s coordinating logistics for the final stretch of the United Farm Workers’ march from Delano to Sacramento, scheduled to end this Friday.

Friends and family see in Andres the spiritual and spitting image of Cesar, down to the same warm smile and eyes, empathetic countenance and healthy head of hair.

“He’s a very strategic and brilliant thinker,” said Cal State Bakersfield President Lynnette Zelezny, who appointed Andres to her Latina/Latino Advisory Committee. She credits him with helping his alma mater open the campus for COVID testing and vaccines, and for working with Dolores Huerta to convince the academic senate to offer ethnic studies. “Andres has that ability to bring people together. He’s a magnet.”

“He doesn’t give thundering speeches that give you chills. He just talks to people, just like my dad,” said Paul Chavez, who heads the Cesar Chavez Foundation and is Andres’ father. “He’s conscious of the message that he has. But it’s a romantic notion that the two are similar. Each is their own man.”

The 28-year-old downplayed any comparisons, or any ambitions on his part to burnish his own image. His job right now is to elevate his grandfather at a time where he said interest in Cesar is bigger than ever.

“A lot of people looked at themselves over these past couple of years and asked, ‘What more can I do?’” he said as we concluded our tour. “So they looked back in history. And they find the farmworker’s movement. The UFW was never big. But there were millions of people who were inspired.

“He was a cool-ass dude,” Andres concluded as we finally settled in a bench under the shade of an oak tree. “But there are less and less people who worked with him. A lot of younger people, they don’t know what my Tata did,” using a Mexican Spanish term of affection that roughly translates as “Grampy.”

Andres never got to meet his grandfather, who died nine months before Andres was born. But he was at UFW rallies almost from the moment he could walk. His father, aunts and uncles all carried on their patriarch’s work through the organizations he had set up.

Nevertheless, continuing in the family business wasn’t preordained.

He moved out of La Paz at 18 and earned a bachelor’s degree in public administration in 2016. Then, he moved to Sacramento to work with a nonprofit that focused on educational outreach for farmworkers, and then the California State Fair.

“I didn’t know what I wanted to do,” he admitted.

About a year into his gig, Andres called his father.

“He said, ‘I’ve been thinking — I want to come back,’” Paul Chavez said. “‘I want to be part of the movement.’”

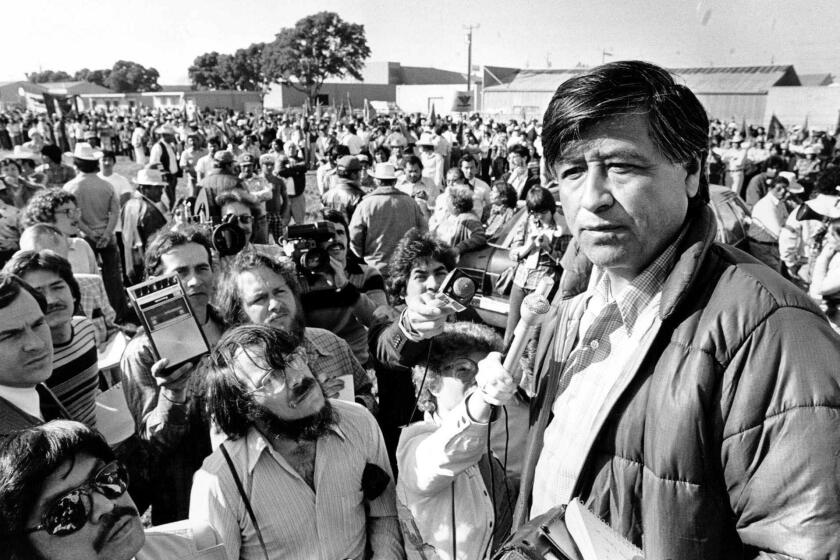

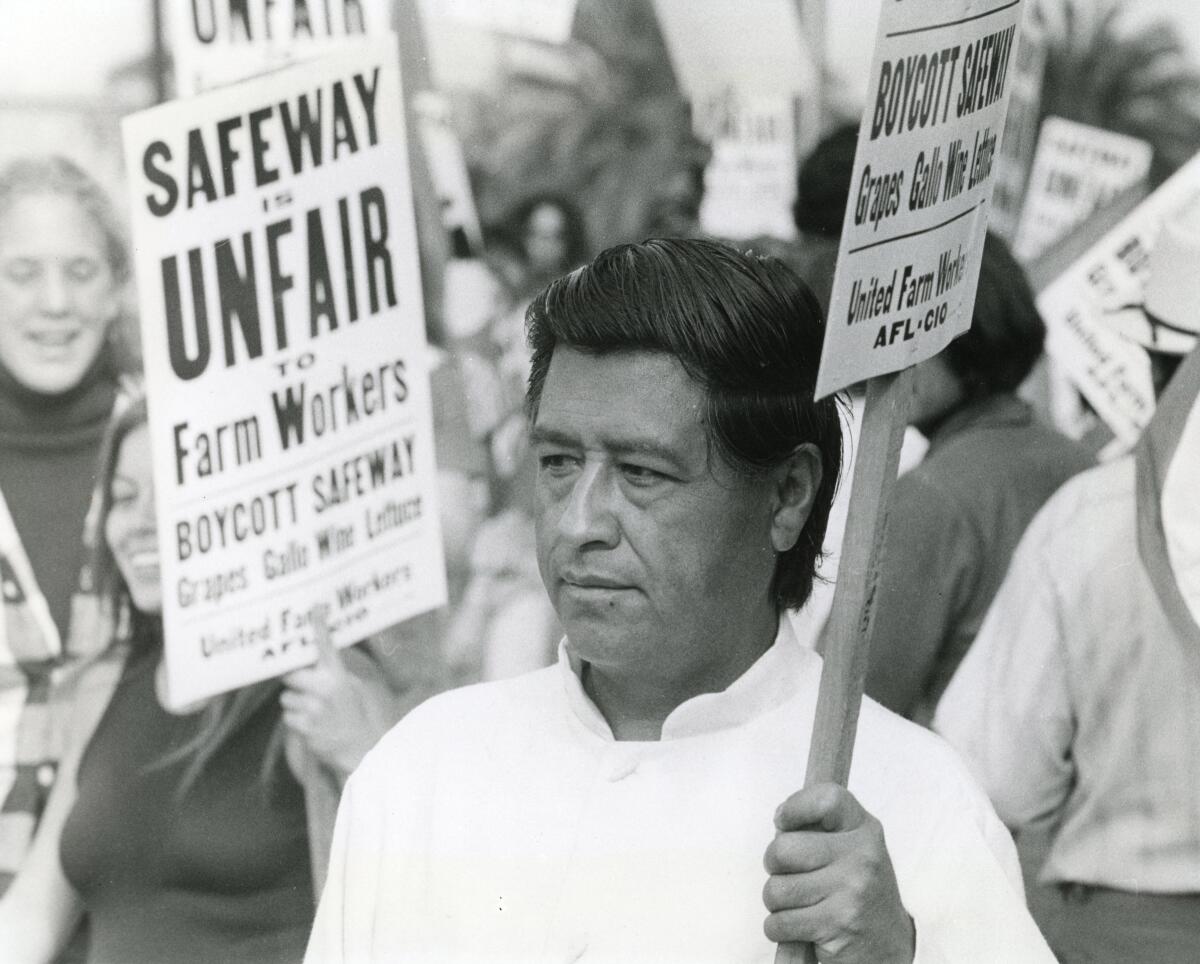

Labor: A spiritual and political leader, he galvanized support for the plight of poor farmhands.

Paul hired his son as an assistant on a 10-year strategic plan for the Cesar Chavez Foundation, which is involved in everything from affordable housing to curriculum training to public health initiatives.

“Being in the movement, you’re exposed to other people, but you’re sheltered from the outer world,” Paul said. “We knew we needed a different focus, and it was obvious he was the guy to do that.”

When the National Chavez Center executive director role opened up and Andres expressed interest, Paul had a frank talk with his son about the promise and peril of the position.

“I told him, ‘Listen, mijo, of course there’s a lot of benefits of being your grandfather’s grandson,’” Paul said. “‘But you gotta understand you’re going to have some tough times too. And you have to be comfortable with dealing with situations that many of us old-timers get defensive about.’”

Paul was referring to revelations in books and newspapers —including this one — over the last 20 years about Cesar’s treatment of former colleagues that have soured his reputation in some progressive circles. And the Chavez family has long fended off accusations that the network of nonprofits they work for and control exploits their patriarch’s name while forsaking the plight of migrant workers.

It’s a past that Andres was more than willing to discuss with me.

“There were some things he could’ve done better — we acknowledge that,” Andres calmly said. “You have to be honest when you think there were things that could’ve been done better, but also look at the longer picture.”

I asked about his grandfather’s use of the term “wetback” and long-standing opposition to illegal immigration, stances that have made him an unlikely cudgel for anti-immigrant activists.

“Is that something we’re proud of? Absolutely not,” Andres said. “But my Tata supported [the 1986] amnesty. By calling him anti-immigrant, you give corporations a big pass on the atrocities of what they were doing. They don’t care about workers — my Tata did. We need to get context like that out there.”

Arellano: Woke California pays homage this week to another American hero with a complex legacy

Cesar Chavez, the most famous Latino activist in U.S. history, is a modern-day secular saint. So his flaws — and he has them — may be tough to accept.

Maintaining and defending his grandfather’s legacy is just part of Andres’ responsibilities as head of the National Chavez Center, which also helps manage the monument with the National Park Service. He’s overseeing the refurbishing of the old La Paz buildings in time for the centennial of Chavez’s birth in 2027, as well as making the area more of a field trip destination.

“Kids from the city deserve to be up here in the wilderness — it’ll be one of the few times they leave an urban environment,” he said.

He wants to get his grandfather’s presence more into the modern age, with gestures as big as a book of his quotations and as small as a Spotify playlist (Cesar was a huge jazz fan, with Coleman Hawkins a particular favorite).

More importantly, though, Andres wants the world to know that Cesar was more than just the fields.

“Every one of my Tata’s causes are current-day issues,” he said. “His ideas were radical for his time. Vegetarianism. LGBT equality. Environmentalism. Police brutality. He even did yoga before it got mainstream. A lot of what he’s known for is pretty glossy now, but there’s so much more.”

We looked at the parking lot, where more and more people were showing up.

“There’s now a lot of Subarus,” he joked, “instead of just Chevys.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.