For family of Trader Joe’s store manager killed by LAPD, impending trial brings anger

- Share via

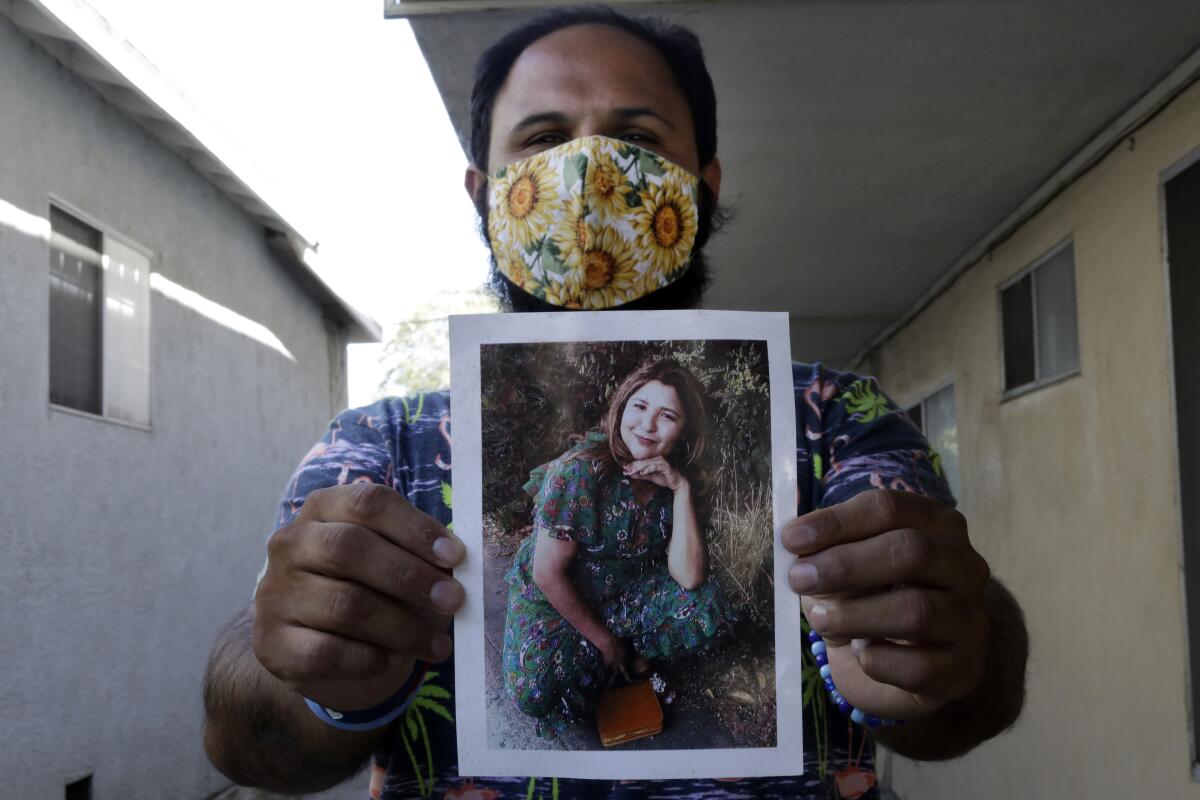

Albert Corado Sr. keeps his daughter’s number in his phone’s list of favorite contacts — even though he knows no matter how many times he calls, she won’t pick up.

Dialing the number makes him feel closer to her, if only until the call goes to voicemail.

It’s been nearly five years since Melyda “Mely” Corado was fatally shot by a Los Angeles police officer who was firing at a fleeing suspect. Her family has sued the city and the officers involved in the shooting, alleging that they opened fire recklessly into a crowded store. The trial is expected to begin in October.

Corado can’t stop thinking about that horrible day. A friend had called to tell him there was a shooting at the Trader Joe’s in Silver Lake where Mely worked. Frantic, he tried her cellphone. She didn’t answer. He called the store, but the line rang and rang and rang. He stopped by the store on his way home to find a sea of police cars, lights flashing.

Before the shooting, Corado still wasn’t done healing from the death of his wife — the mother to Mely and her brother, Albert Jr. — from cancer in 2003. He learned to push the hurt aside so he could be present as a father. He and the kids learned to lean on one another. Then he lost Mely.

Albert Jr. channeled his grief into political activism. Last year, he ran a long-shot campaign for the Council District 13 seat, arguing for abolishing the Los Angeles Police Department and investing in non-police alternatives. He lost in the primary; the race was eventually won by longtime labor organizer Hugo Soto-Martinez.

Corado said his relationship with his daughter had helped him endure after his wife’s death. He remembered the bright-eyed youngster looking over at him once and saying, “Oh, Daddy, don’t worry. I’m going to take care of you.”

“We had so many plans,” he said. “We live in pain every single day.”

Mely was fatally shot on July 21, 2018, after two police officers pursued a man suspected of shooting his grandmother in South Los Angeles and then taking a young woman hostage. Gene Evin Atkins led the officers on a lengthy car chase with the hostage in his grandmother’s car, prosecutors allege.

The chase ended at the Silver Lake Trader Joe’s on Hyperion Avenue. Atkins stopped the car and ran toward the store, which was crowded with Saturday afternoon shoppers.

As he sprinted, police say, Atkins shot at the officers, who returned fire as he entered the store. One of the officer’s bullets struck Mely, killing her. Atkins was wounded in the arm, but he held shoppers and employees hostage inside the store for three hours before surrendering.

The shooting generated fierce criticism of the Los Angeles Police Department. Chief Michel Moore later referred to the shooting of a bystander as “every officer’s worst nightmare.”

Atkins, who under state law is considered criminally responsible for Corado’s death, has pleaded not guilty to 51 felony counts, including murder, kidnapping, premeditated attempted murder and attempted murder of a peace officer. His next pretrial conference is set for May 10.

A department investigation found that the officers who shot at Atkins — Sinlen Tse and Sarah Winans — acted within policy. The two, who both remain with the department, were later cleared of criminal wrongdoing. Department officials have not identified which officer they believe fired the shot that killed Mely.

“We always send our condolences to those families even though we can’t comment further about the case specifics,” said LAPD spokeswoman Capt. Kelly Muniz, citing the pending litigation.

Police shootings are statistically rare; those involving bystanders even more so. But several such shootings in recent years, including the high-profile deaths of Mely and Valentina Orellana-Peralta, have raised questions about the use of deadly force in crowded areas. Orellana-Peralta was 14, shopping with her mother at the Burlington store in North Hollywood, when she was killed by an LAPD officer shooting at an assailant.

In a presentation at the Police Commission meeting Tuesday, LAPD Capt. Scot Williams said officers have to qualify regularly at the weapons range, needing a minimum score of 160 out of 200. A “deep dive” review of 11 years’ worth of LAPD shootings, however, found officers are far less accurate in real life.

Over that span, officers on duty fired about 321 rounds per year — an average of 8.9 rounds per shooting. Just 28% struck their target, said Williams, who runs the Critical Incident Review Division.

Inconsistent record-keeping at other police departments makes comparisons tricky, he said. In 2022, LAPD officers fired fewer rounds (216) than the annual average of the previous 11 years and had a higher “hit percentage” (31%), Williams said.

Even before their mother’s death, Albert Jr. and Mely were exceptionally close.

They bonded over trips to the pool and snack runs to the AM/PM gas station near their home in the San Fernando Valley. He still can’t drive past the AMC theater in Burbank without thinking of the times growing up that their dad would take them to the movies there. Breakfasts at Rick’s Drive In & Out will never be the same without her, either.

Albert Jr. gets angry when he thinks back to a conversation he had with Chief Moore the day after the shooting, in which Moore said the police would provide more answers. That hasn’t happened, he said.

Nor have the politicians who met with the family made good on their promises to hold police accountable. Instead of a “huge reining in of LAPD” after Mely’s death, he said, the city has since gone to great lengths to defend the actions of the officers involved.

After moving to Minneapolis for a few years, Albert Jr. flew home to California the day after Mely died and hasn’t left since. In his grief, he found community with local activists who felt the police made cities less safe, showing up at rallies and news conferences with signs bearing Mely’s name.

With every new police killing in Los Angeles and beyond, he became more convinced that the current system of policing was beyond repair and needed to be replaced.

Frustrated with the pace of change, he ran for City Council last year. He also began attending court dates for other families suing over LAPD violence, hoping they will reciprocate when his case goes to trial later this year.

“If you’re having to listen to city attorneys make their case [about] why it’s OK that the person you loved the most in the world died, it’s not a system that’s set up for us to ever get true justice,” Albert Jr. said in an interview last fall. “We’ve asked nicely, we’ve sent our lawyers in and said, ‘Hey we want to figure this out.’ We’ve done everything.”

At first, Corado was heartened by the support that flowed after Mely’s death. Over the next few months, though, his grief hardened into anger. It felt as if the world had stopped caring about his daughter.

The phone stopped ringing with concerned calls from friends or journalists seeking quotes. Social media largely moved on to the next tragedy. And the politicians and police officials who’d been on TV news for days after her death promising accountability were suddenly nowhere to be found.

Secretly, he started to loathe it when people came up to him and offered platitudes about the need for healing.

As the months went on, he slowly began to shut himself off from the world. He stopped going to church regularly — “I go to Mely, she’s my saint, she’s advocating for me,” he told himself. He started to see a therapist, who told him that “grieving is the price you pay for loving.

“And it’s true, if you don’t love, you don’t feel anything. And I do love my kids,” he said.

And he kept calling Mely’s cellphone, praying that she could hear him “from heaven.”

Eventually, the number was assigned to someone else. Still, he kept calling. He would let the phone ring until it went to voicemail. If the number’s new owner — a man — answered, he would quickly hang up.

Then one time, Corado decided to stay on the line.

“And now there’s a guy who answers and then the guy says, ‘Why do you keep calling my number?’” he recalled. “I explained it to him; I was crying.”

“And he said, ‘Look, you can call anytime you want. I won’t pick up the phone.’”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.